Ralph William Keeney

B-24 LIBERATOR PILOT, 492ND BOMB GROUP, 8TH AIR FORCE, EUROPEAN THEATER

"It would be an exaggeration to say that the B-24 won the war for the Allies. But don't ask how they could have won the war without it."

- Stephen E. Ambrose, The Wild Blue: The Men and Boys Who Flew the B-24s Over Germany 1944-45

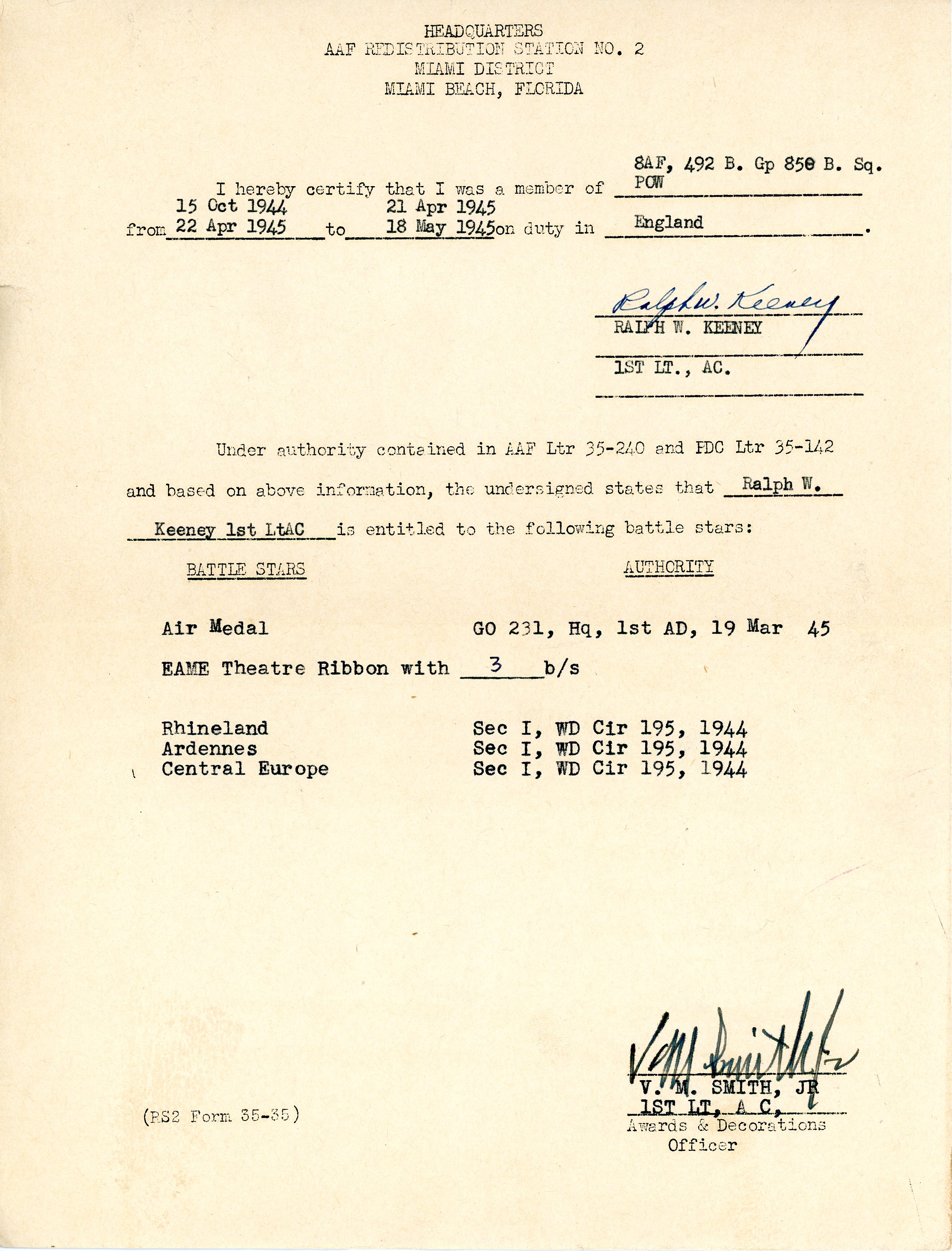

Ralph William Keeney, age 25, my father-in-law, enlisted in the US Army Air Force on December 10, 1942. Upon completion of basic and flight training, he joined the 492nd Bombardment Group, 8th Air Force as a B-24 Liberator pilot. During his time with the 492nd, he flew 21 combat missions over Europe including Operation Carpetbagger missions providing supplies to resistance groups in enemy-occupied countries. During his last mission, his aircraft (Tiger's Revenge) was shot down over Norway and he was rescued and hidden from German forces by the Norwegian underground.

In writing this description of Ralph's World War II experience, and in particular the events surrounding the downing of his aircraft over Norway and his subsequent rescue, I have reviewed a number of published sources describing Operation Carpetbagger and the activities of the Norwegian resistance. Those sources are listed at the bottom of this page. I did consider obtaining Ralph's Official Military Personnel File (OMPF) from the National Personnel Records Center, until I learned that the records of Army personnel for the period 1912 through 1959 were destroyed in a fire on July 12, 1973.

Fortunately, I had access to two excellent sources of information specific to Ralph's experience: 1) Information Barbara (Keeney) Andressen, Ralph's daughter, collected, organized, and documented in notebook format for family members, entitled "Keeney In Norway". This extensive collection included service records regarding his training, assignments, awards, and MIA experience and well as newspaper articles and correspondence with fellow crew members and members of the Norwegian resistance; and 2) the excellent website (www.b24.no) constructed by Norwegian Magne Hvilen and others (see credits on the site). The site's homepage explains, "This is the story about ten American airmen and their aircraft that crash landed in Brunlanes, Norway on the 21st of April 1945."

In addition, in November 2007, my son and Ralph's grandson Kevin Moore, visited Norway and was given a wonderful tour by Magne Hvilen and his wife Kjetil. They visited many of the locations specific to the crash of Tiger's Revenge and the rescue of Ralph and his crew members. He brought home with him some great pictures and stories related to him by former members of the resistance and their relatives and friends.

This webpage is dedicated to the memory of Ralph Keeney and the service he and his fellow crew members provided to our country in time of war, and to Barbara (Keeney) Andressen who devoted so much time and effort in documenting her father's experience during World War II. It also recognizes the extraordinary efforts put forth by members of the Norwegian underground (Milorg) to provide aid and assistance in rescuing American airmen shot down over their country.

Enlistment and Training

Ralph William Keeney enlisted in the US Army on December 10, 1942 at the age of twenty-five. As indicated on his draft registration card (Figure 1), at time of his enlistment he had been working for the Woodward Governor Company in Rockford, Illinois for several years. The company was then heavily involved in manufacturing aircraft parts to support the war effort. This work experience no doubt played a part in Ralph's selection for pilot training.

The best documentation I have of his training record after enlistment is his "POM Individual Qualification Card - Heavy Bombardment" (Figure 2). His early training record has some unexplained gaps owing to my lack of information regarding that period. The first documented school was "CTD Spearfish, Cal." for 2 months ending 12 May 1943. So there was a period of a few months between when he enlisted and when he attended his first school; which may be explained by a delayed reporting date after enlistment or perhaps an initial "boot camp" required of all enlistees. There is another gap of about 2 months until he attended Preflight school for 2 months ending 1 September 1943. This may have been a waiting period that included testing and evaluation to determine the Army discipline he was best suited for; which resulted in his entry into the Aviation Cadet pipeline. From then on, his schooling was more or less continuous until he was fully qualified as a B-24 pilot.

Aviation Cadet Keeney attended Preflight school at Santa Ana Army Air Base (SAAAB), Santa Ana, California. At SAAAB, he received 2 months of military induction and fundamental ground training in the physics of flight and completed the course on 1 September 1943.

The aviation recruit's first experience with military life came in Preflight. In this stint (whose length varied), he learned basic military courtesies, personal hygiene, rifle drill, marksmanship, the rudiments of code communications, and a respect for Army ways. As an aviation cadet, he was lower than the lowest enlisted rank in the Army, and as yet nowhere near an airplane.

Source: Training to Fly - Military Flight Training 1907-1945During the war years, after Preflight, Aviation Cadet training involved three phases: Primary, Basic, and Advanced. The majority of the training received was through contracts with private flying schools using civilian trainers (former and current military and civilian pilots for the most part).

"..to employ men whose physical condition and whose age would not admit them to the military service as pilots, but who could nonetheless serve as instructors, and very able instructors, of primary students. It was a wise course to follow, I thought." - Lt. Jacob E. Smart, Gulf Coast Training Center

Source: Training to Fly - Military Flight Training 1907-1945After Preflight training was completed on 1 September 1943, Cadet Keeney moved on to the Primary school at Ontario Army Airfield, Ontario, Calif.

At Primary school, "At last the cadet climbed into an airplane. An experienced pilot would teach him to fly. Whether it was 1922 or 1942, the beginner still felt an anxious tightness in the chest when approaching the first solo flight, horror and denial on witnessing the first fatal accident, wonder and disorientation on the first night mission, and the temptation to fly by the seat of the pants rather than by instruments. Thoughts of combat brought a rush of exhilaration; fear came at the prospect of washing out, which was viewed as unequivocal failure. As one airman put it, 'it sounded as though you turned colorless and just faded away, like a guilty spirit.'"

Source: Training to Fly - Military Flight Training 1907-1945

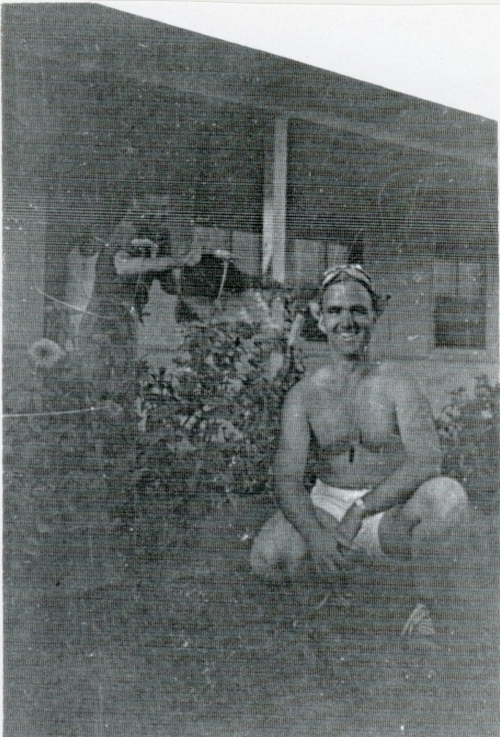

"This was the day I soloed, and as I was the first in the squadron, I got the works, only I didn't know it was coming. The gent throwing the water lives in the next room with two other "deep south" gentlemen. They're all good Joes. Just about 1/10th of a second after this was snapped, I almost jumped as high as the cottage."

Source: Ralph Keeney in a letter home during Primary School.At the end the Primary phase, cadets were evaluated to determine if they were best suited to be pilots, bombardiers, navigators, mechanics, etc. Upon completing the Primary School course on 3 November 1943, Cadet Keeney was selected for pilot training and was transferred to Lemoore Army Airfield in Lemoore, CA for Basic flight training.

"Primary can make mistakes - Basic will correct them; Basic can not make mistakes because Advance has no time to fiddle with corrections of technique." - Col E. B. Lyon, Commanding Officer Basic Flying School, Moffett Field, CA

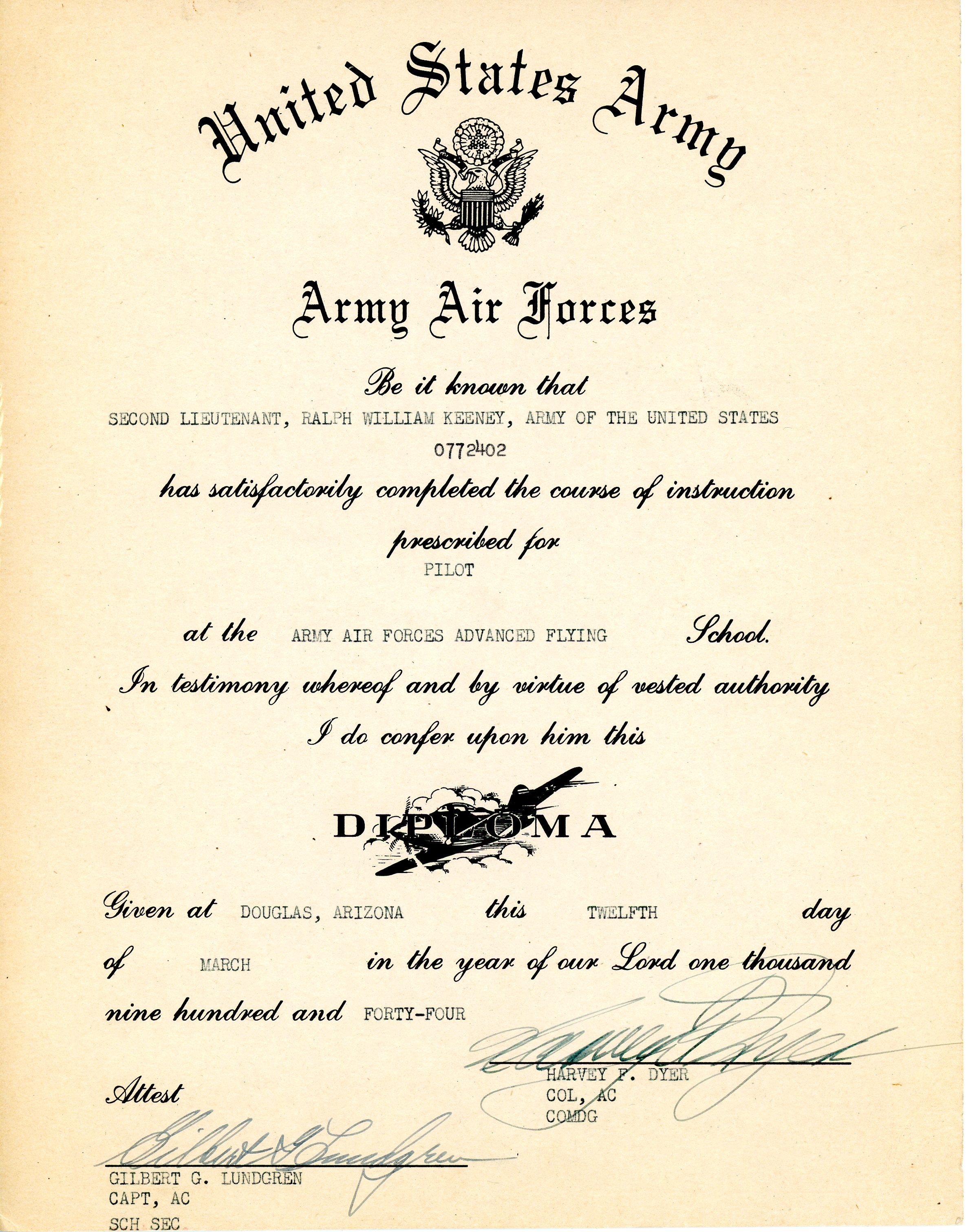

Source: Training to Fly - Military Flight Training 1907-1945After 2 months of Basic flight training, ending on 7 January 1944, Cadet Keeney entered Advanced flight training at Douglas Army Airfield - Advance Flying School, Douglas, AZ. Advanced training meant specialization in single- or twin-engine aircraft. At the time of Ralph's entry into advanced training, there was a much greater need for bombardment pilots and he was selected for twin-engine specialized training.

"Students had not previously controlled two engines that demanded adjustments even in taxiing. Moreover, although the advanced course focused upon individual proficiency, in learning to fly a multiplace airplane that might carry a copilot, a navigator, a bombardier, and a number of gunners, the pilot was introduced to the crew concept. A man had to communicate with others at the same time that he performed his own tasks. He had also to rely unquestioningly on the ability of others. If a twin-engine pilot was to become an airplane commander, he had to demonstrate qualities of leadership and a sense of responsibility for his eventual crew’s performance and coordination."

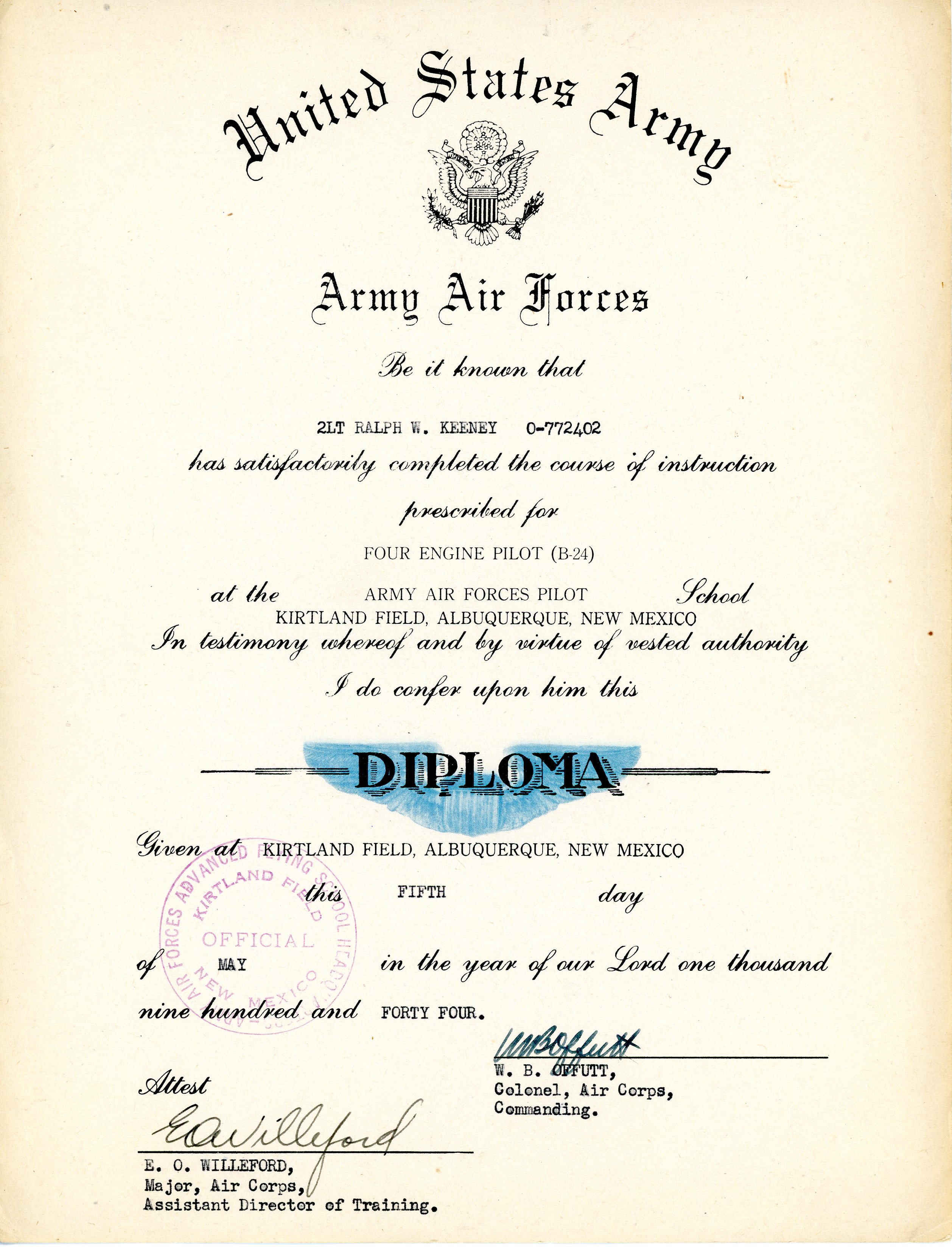

Source: Training to Fly - Military Flight Training 1907-1945Cadet Keeney received his formal diploma upon graduating from Advanced Flying School on 12 March 1944:

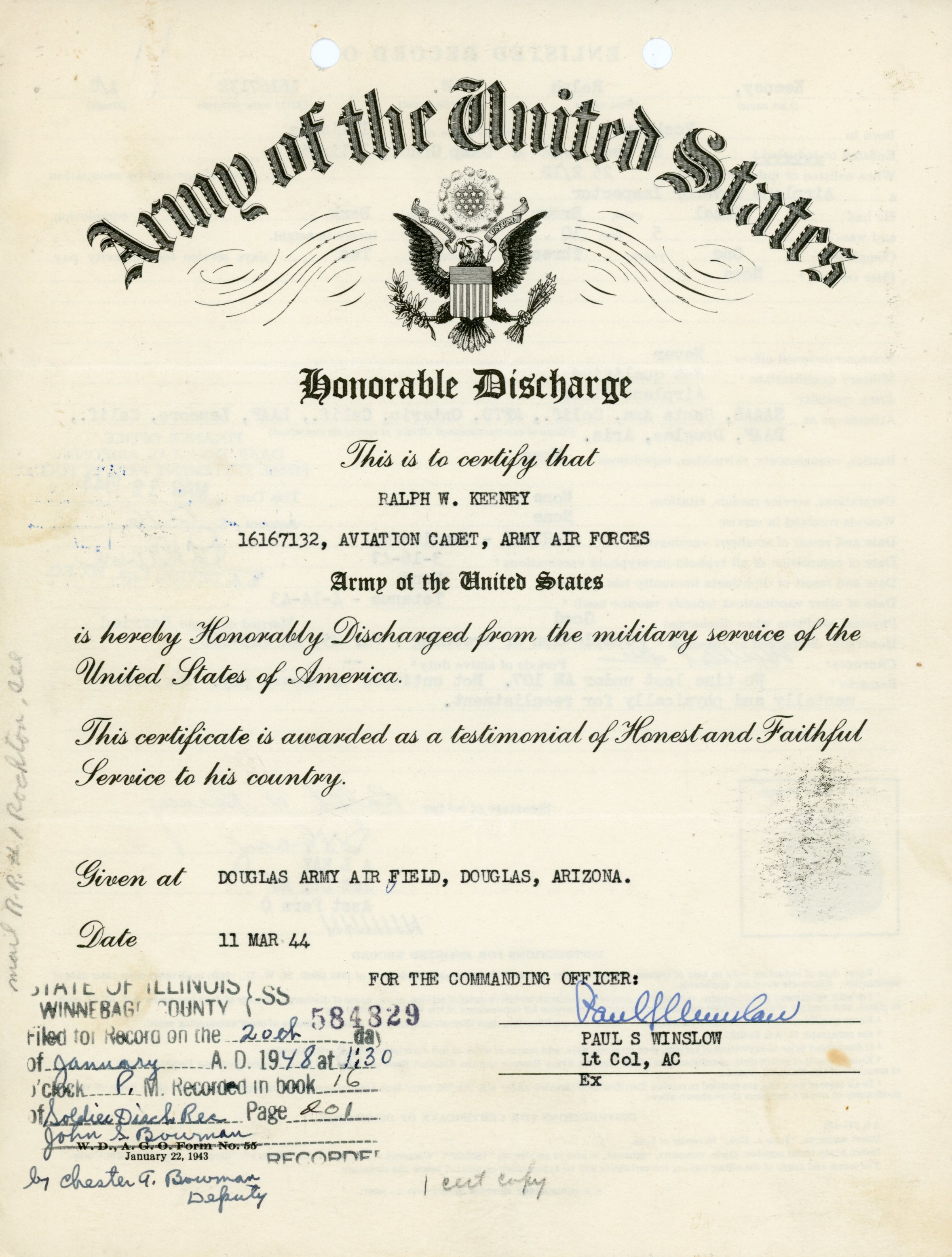

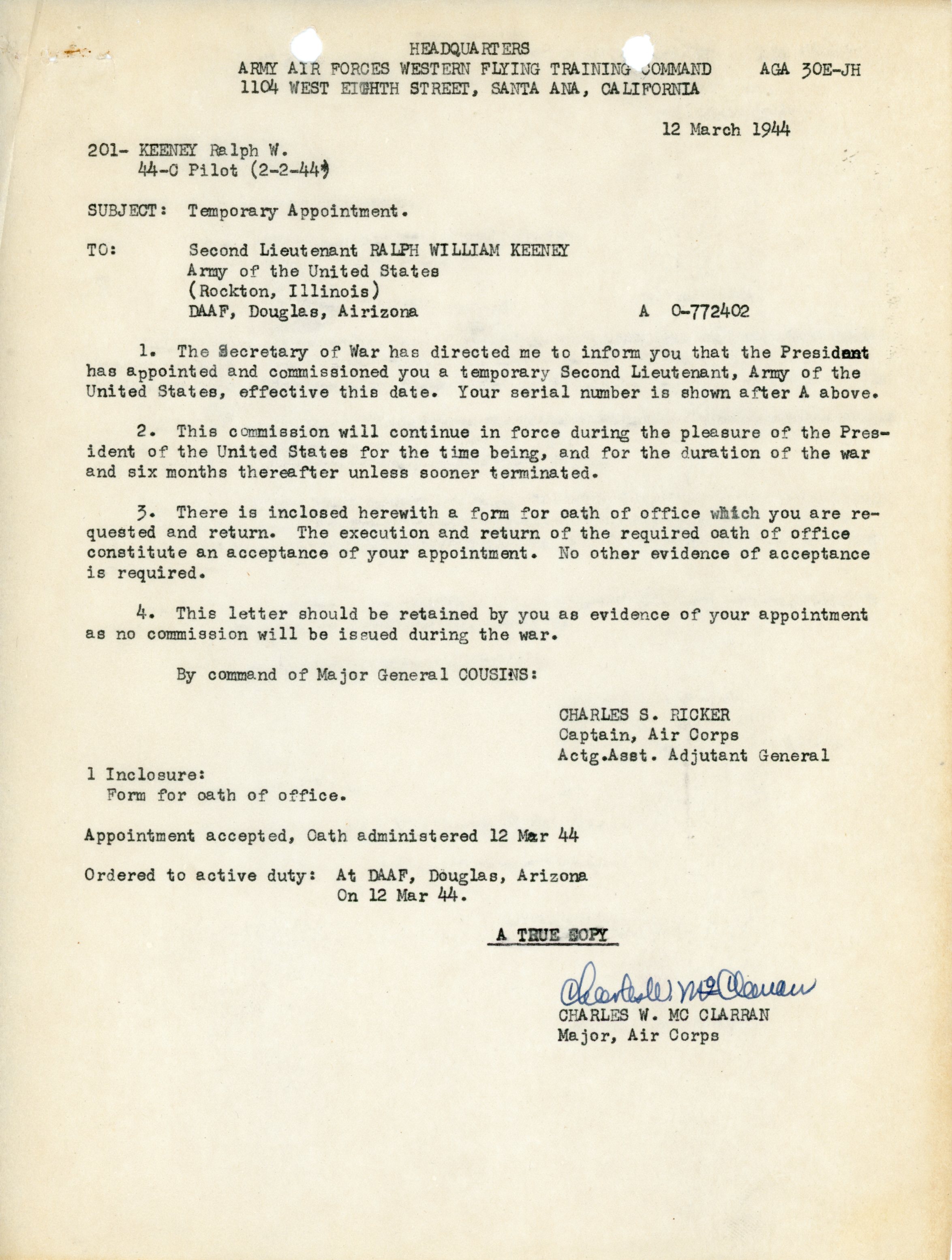

Aviation Cadet pilot candidates successfully completing the course of instruction prescribed for pilots at the Army Air Forces Advanced Flying School, received their pilot wings and were honorably discharged from enlisted status, appointed as commissioned officers at the rank of 2nd Lt., and given orders to active duty as officers.

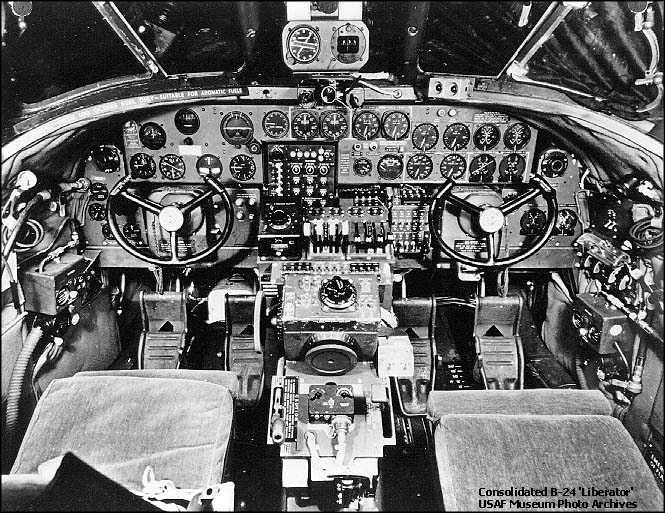

Lt. Keeney's first duty station as an officer was at Kirtland Air Force Base, Albuquerque, New Mexico. There he spent 2 months in "transition training", i.e., transitioning from aircraft used for training to a specific combat aircraft; in Lt. Keeney's case, learning to pilot a B-24. He graduated from this course on 5 May 1944.

"Transition was both the last step of individual proficiency training and the first step in operational training. The bombardment pilot started his formal transformation into an airplane commander during transition. By the spring of 1944, transition included six hours on the duties and responsibilities of the airplane commander. Graduate pilots reviewed the responsibilities of an officer and the code of military law; the organization and policies of operational and replacement training; the duties, responsibilities, and obligations to crew members; the duties of ground and air crew; and the importance of air discipline. Returned combat pilots gave an account of their crew training and experiences in the theaters. Despite the indoctrination, an inspector who visited the specialized four-engine school at Liberal Army Air Field, Kansas, observed that proficiency as an airplane commander was difficult to obtain during transition. 'It is a new phase of training to students graduating from advanced flying schools, and who have had no command experience whatsoever.' Pilots were new to the equipment and carried no crew during the transition phase, and because the instructor was in command of the airplane at all times, the inspector explained, 'it is difficult to set up practical experiences for the students.'”

"For heavy bombardment, pilots transitioned onto B-17s or B-24s. Through the midpoint in the war the tactical training units asked for an equal number of B-17- and B-24-trained students, but the Training Command had a greater number of B-17 aircraft. It finally acquired more B-24s and converted schools from one type to the other as the need arose. The curriculum in each was similar, but because the B-24 was a more difficult airplane to fly, the B-24 course added hours during 1942 and 1943. The B-17 course lasted 9 weeks and had 105 flying hours, in comparison to the B-24 course which went to 125 flying hours before reverting to the B-17 course specification in February 1944."

"Air work included day and night transition; instruments; formation, high altitude, and navigation missions; and 15 hours of practice in the Link trainer. Technical instruction in both theoretical and practical engineering maintenance dominated ground classes. Navigation, radio, meteorology and weather, aircraft recognition and range estimation, naval forces and ship recognition, first aid, oxygen, code review and signal lamps, chemical warfare defense, and athletics occupied the rest of students’ time. Transition and instrument training accounted for the increased hours in the B-24 course. Revisions in the course between April 1943 and February 1944 increased instruction in the use of the autopilot and allotted more hours to navigation and airplane commander duties. The 1944 program included bomb approach training."

Source: Training to Fly - Military Flight Training 1907-1945

Below is a short video showing what it is like to fly a B-24. Note at about 4:26 the pilot states, "...it is one of the hardest planes in history to fly."

Lt Keeney's next duty station was Tonopah Army Air Field, Tonopah, Nevada. There he joined the 422nd Army Air Force Base Unit, RTU Heavy Bombardment for combat crew flight training (RTUs, Replacement Training Units, turned out crews that went overseas to replace crews already in theater). The enlisted members of the crew (all but Bob Broadus - Engineer) arrived at Tonopah on or about May 16, 1944. By May 22, the crew membership was fully known and the officers (except Jack Devine - Navigator) were present. By early June, Broadus and Devine were on-board and the Tiger's Revenge crew was fully assembled (designated Crew #207) and introduced to one another (see below under the heading "Tiger's Revenge" for a listing and pictures of crew members).

The objective of crew training was to create a well-coordinated team with competence in areas such as formation and high-altitude flying, night-time navigation, instrument flying, aircraft defense, and bombing accuracy that would be required for success and survival in a combat enviroment.

"Ultimately, war brought an inevitable, unbridgeable gulf between training and combat. When men left training, they went to fight, not merely to fly. Normal peacetime air training levied an exceptionally high casualty toll compared to other Army combat arms, and although death under these or any circumstances came neither fearlessly nor clean, now airmen did not go down only because of wind shears, or mechanical failures, or one’s own mistakes. Now the enemy had a human face and intention, and he meant to kill."

"Arnold [Commanding General of the Army Air Forces] therefore exhorted those fighting the war to help motivate young airmen, to tell 'our trainees some of the glamours of war and the great personal satisfaction to be derived from actually hitting the enemy between the eyes.' Here, Arnold voiced an imperative that underlay all combat training, that men must be sent into combat knowing the truth, but not the whole truth. They must be indoctrinated to embrace the battle and hate the enemy. They must be taught how to fight, but not at what cost."

"War brought another psychological element to unit training that was as old and unchanging as the military order itself - the drawing together of men in combat. Remarque’s narrator in the World War I classic All Quiet on the Western Front spoke of it with simple eloquence: 'It is as though formerly we were coins of different provinces; and now we are melted down, and all bear the same stamp.' Airmen on the battlefront during the Second World War reminded those at home that 'crews must be trained as a team, not as a group of individuals.' The need to cement cohesiveness among members of the crew and squadron appeared in AAF OTU guidelines under subjects such as 'duties of the airplane commander' and 'learning to function as a unit.' Esprit d’corps, group morale, and, preeminently, mission accomplishment depended upon mutual trust in the reliability and proficiency of each person."

"Reminders of the bonds that grew between members of that irreducible air force unit, the crew, and, more commonly, among specialists such as the pilots in a squadron can be found in the memoirs, the poetry, and the gallows humor of the men who fought in the air. They started to pull together in their final training on home shores. In a novelistic treatment of his experience flying B-17s, Edward Giering spoke of the crew in training as being 'meshed together like so many cogs of machinery to run as smoothly as the machine they flew.' In Philip Ardery’s analogy, the heavy bombardment crew he joined in El Paso, Texas, took on a living identity: 'When we arrived at Biggs Field we were only the skeleton of a heavy bomber group. Gradually sinew and muscle grew on the skeleton. It became a unit with as much individuality as a person has, and was as different from other organizations of like size and designated purpose as one human being is different from another.'"

"Dive-bomb pilot Samuel Hynes confessed that flying with the radio and radar men of his crew in the Pacific was not 'the bond that flying beside other pilots was. The pilots were my friends but the crew was just a responsibility, like relatives or debts.' Nevertheless, the squadron was 'more like a family than anything else,' Hynes reflected. 'Everyone moved in his own sphere, was free to dislike and fight with the other members ... yet acknowledged that there were bonds that linked him to this group of human beings, and excluded all others. ... It wasn’t a hostile exclusiveness, just a recognition that ties existed.' Once into combat, if you were to die in the smoke and fear and noise of battle above the earth, it would not be with strangers."

Source: Training to Fly - Military Flight Training 1907-1945The Tonopah training was completed on July 28, 1944 and the crew received orders on July 31 to proceed to Hamilton Field near San Francisco, California via rail. During World War II, Hamilton field served as a training facility and a departure point for Pacific-bound air troops. After November 1943, Hamilton was assigned the responsibility to process heavy bombing aircraft and crews for combat overseas. At Hamilton, the crews were issued clothes and equipment needed to perform their mission overseas. After a short stay, on August 6, Lt Keeney's crew was given orders to proceed "to Camp Kilmer, New Jersey, RUAT to the Commanding General, New York Port of Embarkation for further movement to the overseas destination of this shipment by water." The "shipment" was comprised of 15 B-24 bomber crews, including the Keeney crew.

After a long cross-country trip by rail (troop train) which included California, Colorado, Illinois, Ohio, and New york, on August 14, 1944 they arrived at Camp Kilmer, New Jersey. With regard to the accommodations during the trip, crew member Arthur Greenwood offered the following in a letter home: "This, without a doubt, is the dirtiest train that I have ever been on. They have bunks 3-high in the car. The middle bunk can be folded down to form backrests so to sit during the day and back up at night. The locomotive (coal-burning) throws soot over everything that you sit and lie on. You look like you are in a minstrel show! Your clothing is a mess!"

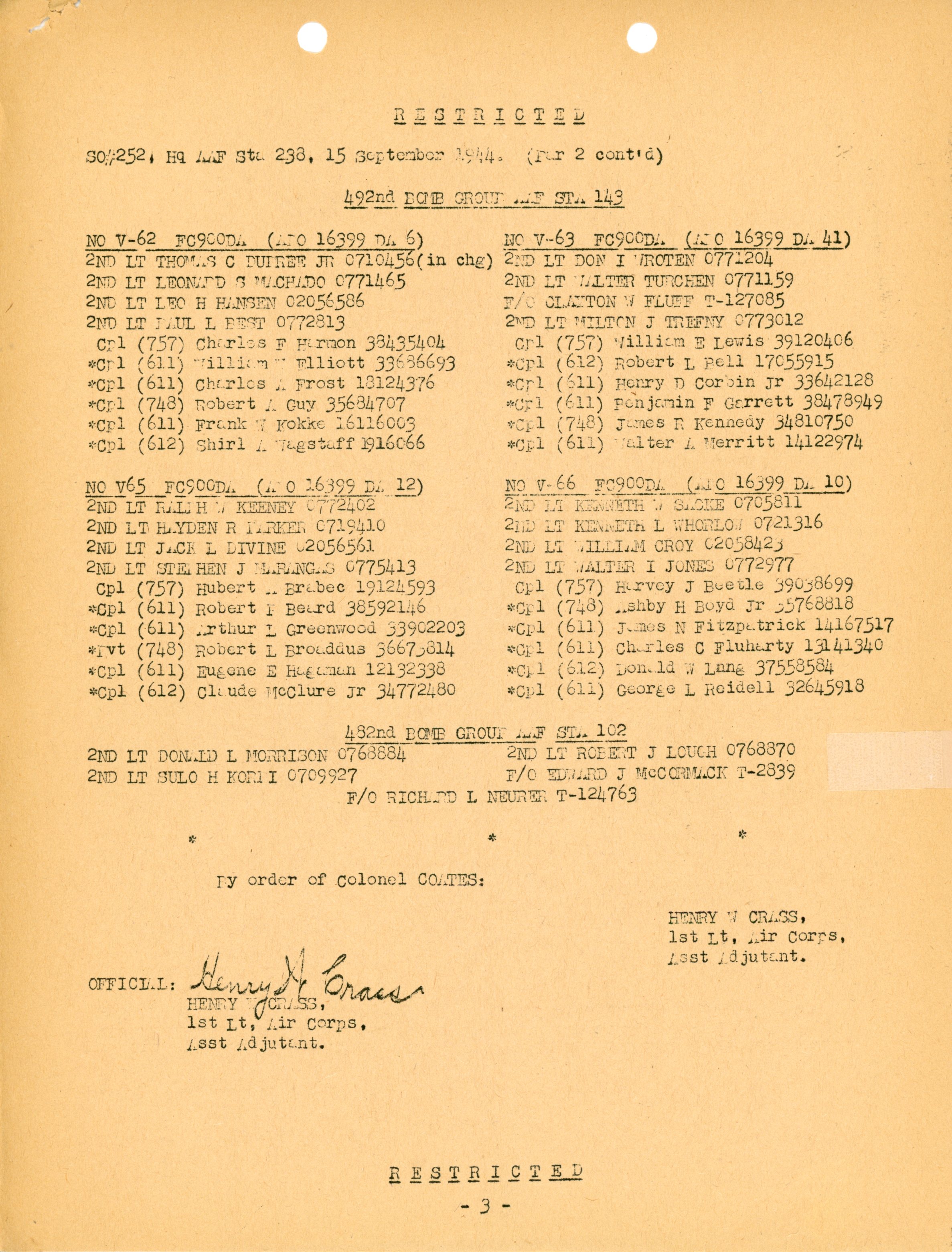

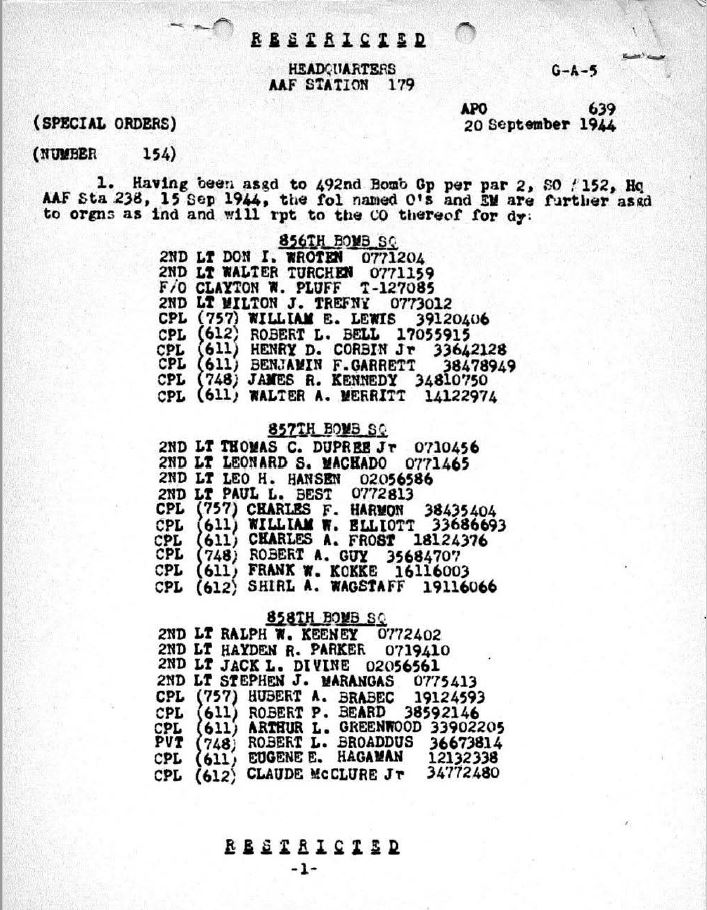

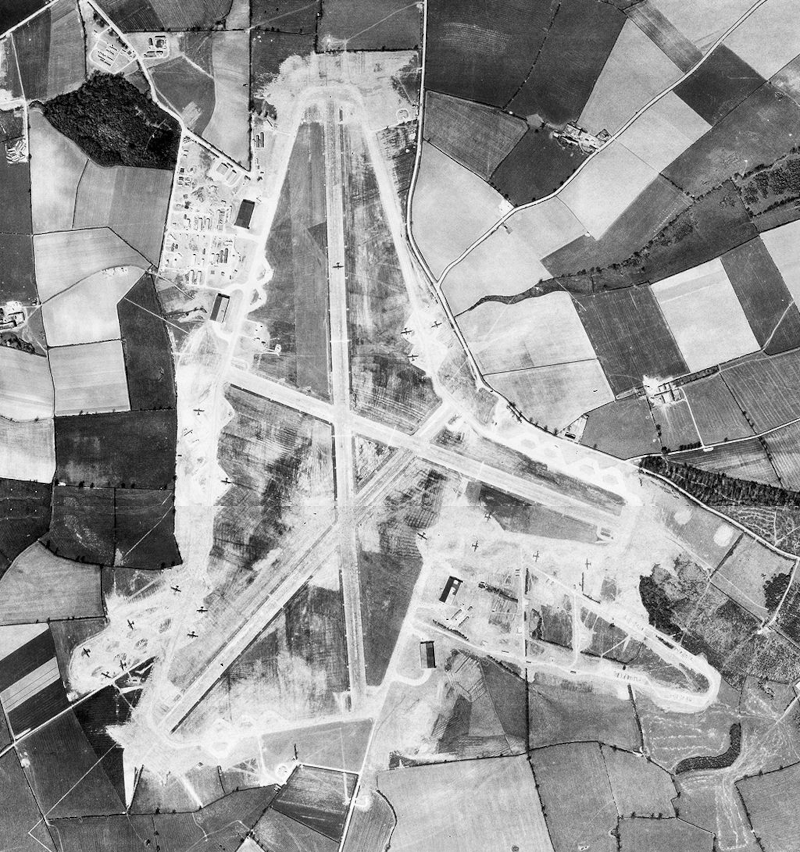

Arriving at Camp Kilmer, the crews were assigned to 2nd Replacement and Training Squadron, Bombardment, AAF Station 238. On September 15, 1944, the Keeney crew were given orders reassigning them to the 492nd Bombardment Group and to proceed "without delay" to that duty station (Figure 9). At that time, the 492nd was officially located at RAF North Pickenham (Station 143) located just east of Swaffham, Norfolk, England. However, those orders were either amended or perhaps were intended to disguise the fact that the 492nd crews were ultimately to proceed to RAF Harrington (Station 179) where the top secret Operation Carpetbagger had been re-located in March of 1944.

In a letter to Magne Hvilen in 2007, Arthur Greenwood clarifies the Keeney crew's activities between leaving Camp Kilmer and arriving at RAF Harrington:

From Kilmer, we boarded the Ille de France French liner from WW-1 from the Booklyn Navy Yard at New York City. After a day or so at sea, we did a 180 back toward New York City to avoid a submarine apparently stalking us as we were NOT in a convoy. This diversion only lengthened our crossing.

Bing Crosby with a USO troupe of entertainers kept our morale high, however, as they took the whole ship groups at a time the whole way over.

Five decks below the waterline were these poor paratroopers from the 82nd and 101st Airborne packed in like sardines. One torpedo and they wouldn't have a chance for survival. I had the good fortune of being on the noncom's deck -- just below the officer's deck -- topside.

We came into Glasgow, Scotland harbor from which we traveled by train down the east coast to Newcastle, England, where we spent a few days.

Then, for some reason, we stopped at an air base where our pilot and co-pilot had some stick-time on a B-17. Our training had been entirely on B-24's. A little puzzling at the time, but a good idea in hindsight.

Shortly afterward, we were flown by B-17 to Belfast, Ireland, for overseas training prior to assignment to a permanent air base. Here they separated the officers and enlisted crew members and sent them to different locations. After training, we boarded a ferry and crossed the Irish Sea to Liverpool, England, where we, again, hauled by truck to a destination in the middle of the night which was to be our permanent base.

The next morning, we curiously looked over our new surroundings. Now that it was daylight. We were amazed to find B-24's painted black on the flightline. And in the bombays contained static lines, straps and canisters instead of bomb shackels.

Upon arrival at RAF Harrington, Station 179, on September 20, the crew received special orders (Figure 10) assigning them to the 858th Bombardment Squadron within the 492nd Bombardment Group.

US Army Air Forces

The United States Army Air Force (AAF) was created on June 30, 1941 as a successor to United States Army Air Corps which had been the aerial warfare service of the US Army since 1926. It was created in recognition of the increasing importance of aviation in military operations and to provide a level of autonomy from the US Army ground force command structure. The AAF remained a part of the Army until reorganization of the military in the post-war period resulted in the creation of an independent United States Air Force in 1947.

With the onset of World War II, the AAF became the first air organization of the US Army to control its own air installations and support personnel. During the war, the AAF expanded to over 2.4 million men and women, nearly 80,000 aircraft, and 783 domestic bases and, over time, assumed control of the conduct of all aspects of the air war in every part of the world, including developing air policy and issuing orders outside of the authority of the US Army Chief of Staff.

Eighth Air Force

The Eighth Air Force was activated on January 28, 1942 and contained three subordinate units: the VIII Bomber Command (BC), the VIII Fighter Command (FC), and the VIII Ground Air Services Command (GASC). The VIII BC was first established at Langley Field, Virginia on February 1, 1942. To serve the needs of the war, at the end of February, the VIII BC moved to England, establishing its wartime headquarters in the Wycombe Abbey school for girls. An army reorganization of its Air Forces in that same month resulted in renaming Eighth Air Force as the United States Strategic Air Forces in Europe and the VIII BC was reassigned as the Eighth Air Force. By the end of the war, the Eighth had assembled the greatest air armada in history and became know as the "Mighty Eighth".

"From May 1942 to July 1945, the Eighth planned and precisely executed America's daylight strategic bombing campaign against Nazi-occupied Europe, and in doing so the organization compiled an impressive war record. That record, however, carried a high price. For instance, the Eighth suffered about half of the U.S. Army Air Force's casualties (47,483 out of 115,332), including more than 26,000 dead. The Eighth's brave men earned 17 Medals of Honor, 220 Distinguished Service Crosses, and 442,000 Air Medals. The Eighth's combat record also shows 566 aces (261 fighter pilots with 31 having 15 or more victories and 305 enlisted gunners), over 440,000 bomber sorties to drop 697,000 tons of bombs, and over 5,100 aircraft losses and 11,200 aerial victories. "

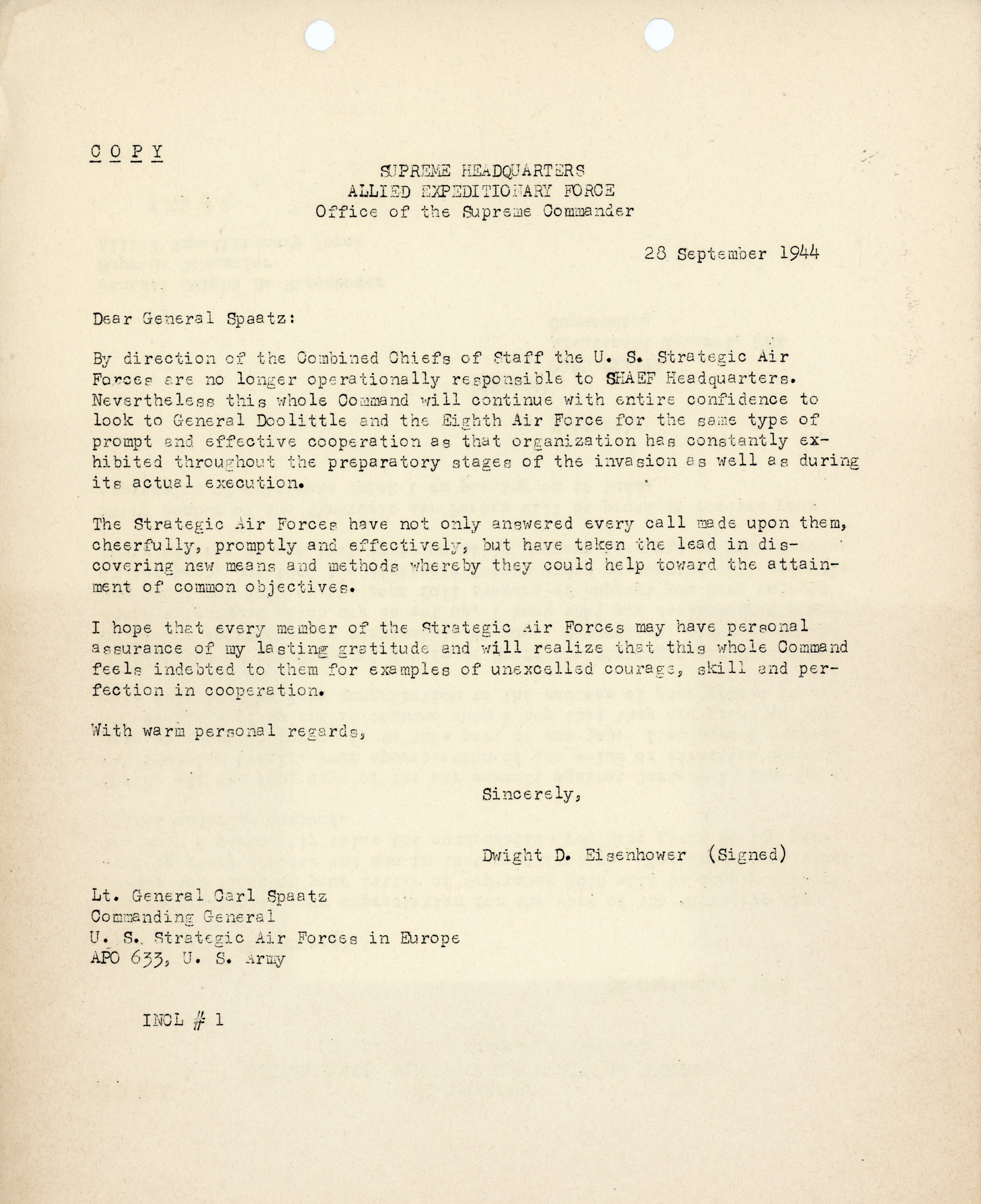

Source: 8th Air Force/J-GSOCThe following letter from General Dwight D Eisenhower, Supreme Allied Commander, was copied to all members of the Eighth Air Force. The letter references the performance of the Eighth Air Force in supporting the D-Day invasion of Normandy, France.

492nd Bombardment Group

There were two iterations of the 492nd Bomb Group during World War II. The first iteration was activated on October 1, 1943 at Clovis Army Air Base, New Mexico. After some shuffling of the group's command structure and changes in its mission, all group personnel of flying status were transferred to Alamogordo Army Air Field, New Mexico. The group air echelon trained at Almagordo until departing for RAF North Pickenham, England on April 1, 1944.

After arrival at RAF North Pickenham, the 492nd entered combat on May 11, 1944. For the next 89 days the 492nd Group (comprised of the 856th, 857th, 858th, and 859th squadrons) flew 67 missions through August, 1944, primarily over Germany but also over France in support of Operation Overlord, the invasion of Normandy on D-Day, June 6, 1944. During that period, the 492nd suffered the heaviest losses of any Eighth Air Force group during World War II. Over those 67 missions, the 492nd lost 52 aircraft with 588 men killed or missing, including one mission alone where they lost 14 B-24s to Luftwaffe fighters. They were dubbed by General Doolittle and his staff as the "Hard Luck Group" because, even though the experienced men within their crews had performed at a high level, they still incurred heavy losses owing to the the circumstances in which they flew their missions. By that point in the war, heavy bombers like the B-24, often flying deep into Germany without fighter escorts, faced a desperate German opponent that was armed with fighters that had been refitted with advanced equipment including improved radar, air to air rockets, and upward firing guns, all developed to attack Allied bombers.

The website www.492ndBombGroup.com does a superb job of telling the story of the original 492nd Bombardment Group, including its history, the missions, and the personal stories and experiences of those who performed those dangerous and deadly missions. I highly recommend the site to anyone interested in learning about the dedicated service the B-24 crews and support personnel provided to our country during World War II.

The 492nd Bombardment Group realized its second iteration when the 8th Air Force was ordered to disband one of its B-24 groups for the purpose of handing over its identity to the American Office of Strategic Services's (OSS) 801st Provisional Group at RAF Harrington, aka the Carpetbaggers. The Carpetbagger Operation, which had been assembled in part from B-24 elements of the discontinued AAF Antisubmarine Command (their mission had been handed off to Navy fliers to free B-24 assests for Europe), had been conducting missions since March of 1944 but needed a working cover to maintain its covert status. To meet this goal, and given the devastation that the 492nd incurred in the three months prior to the arrival of the Keeney crew in England, the decision was made to disband the original 492nd Bombardment Group, and the 801st was redesignated as the new 492nd Bombardment Group on August 13, 1944. The redesignation included the continuing presence of the 492nd's cadre of squadrons. This was the 492nd's status when the Keeney crew arrived at RAF Harrington and joined the 858th Bombardment Squadron.

Operation Carpetbagger

On October 24, 1943, crew members from 22nd Anti-Submarine Squadron that had been operating out of RAF Dunkeswell, Devon, England, were called into their briefing room and told that their mission was to be handed over to US Navy fliers because their skills were needed for B-24 bombardment groups in East Anglia. The next day, the 22nd's commanding officers and squadron commanders, were invited to a highly secret meeting at the US base at Bovington, Hertfordshire, England and informed that they had been chosen to create a special unit to fly agents and supplies to Resistance groups in occupied Europe. They would be working in liason with the British Special Operations Executive (SOE) and the US Office of Strategic Services (OSS) in a top secret project called Operation Carpetbagger. Up until that meeting, the SOE had been solely responsible for such operations. Operation Carpetbagger was designed to ramp up covert Resistance support in anticipation of the upcoming invasion of Europe. As the project evolved, the OSS would oversee the actual operations with advice and co-operation from the SOE.

A few days after the meeting, the 22nd officers and enlisted men were dispatched to RAF Tempsford, to observe and receive training from the RAF Special Unit operating there. In November, the 22nd (and the 4th Squadron/479th Group) Anti-Submarine Squadrons were deactivated and two new B-24 squadrons, the 406th and 36th were formed as part of the 482nd Bombardment (Pathfinder) Group and assigned to RAF Alconbury, near Tempsford. On January 4, 1944, owing to inadequate facilities at Alconbury, the first US Operation Carpetbagger missions were actually flown out of Tempsford. Six missions were flown by the 36th and nine by the 406th.

By Mid-March, 1943, after trying and rejecting three RAF airfields (Tempsford, Alconbury, and RAF Watton) as a long-term home for Operation Carpetbagger B-24s, RAF Harrington, a former B-17 base was evaluated and deemed an ideal home for the Carpetbaggers. The advanced echelons of the 36th and 406th squadrons moved into Harrington on March 25, 1944 and secure communications were established with OSS headquarters in London to provide lists of approved targets to the Group OSS Liaison Officer at Harrington. Shortly thereafter, the two squadrons formed a new Bomb Group to be known as the 801st Provisional Bomb Group; and the squadron's B-24s had arrived and were squatting in hardstands around the perimeter of the airfield. In May, two more squadrons were attached to the 801st Group, the 788th from RAF Rackheath and the 850th from RAF Eye. Finally, as alluded to above, in mid-August, the B-24s of the 492nd, including the Keeney crew's 858th squadron, was added to the Carpetbagger fleet and the 801st was redesignated as the 492nd Bombardment Group.

The Liberators

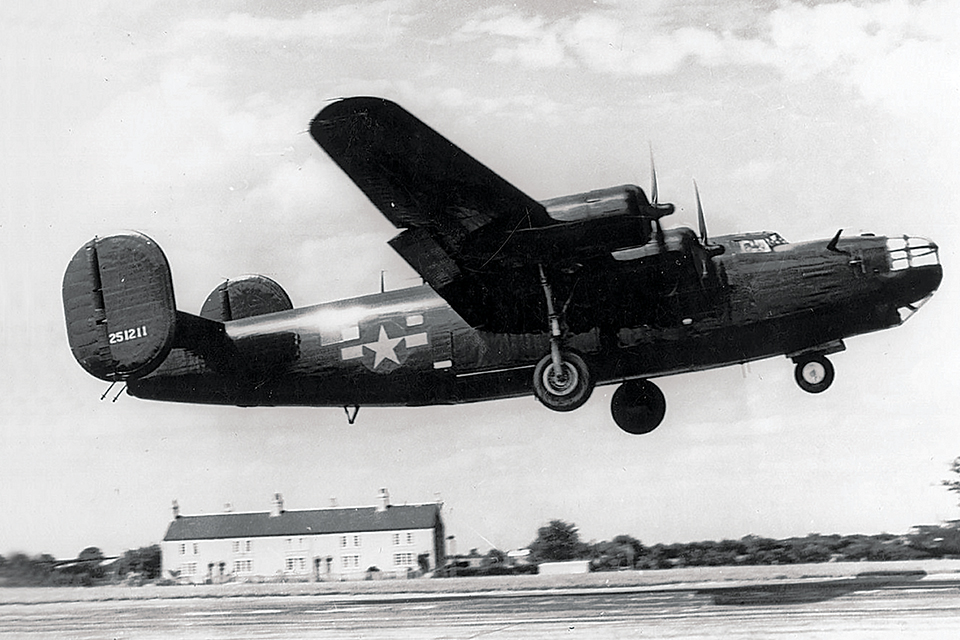

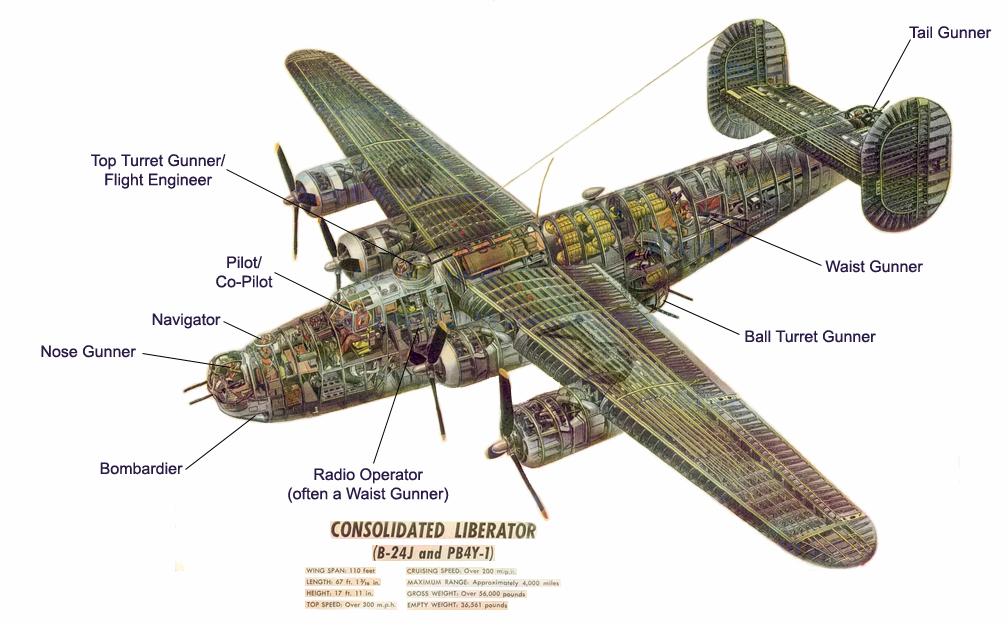

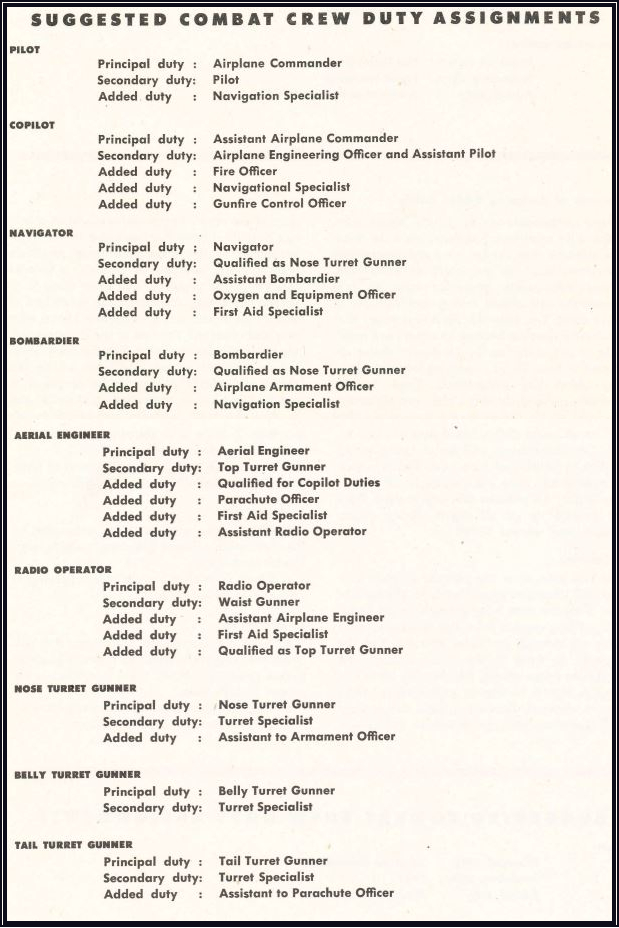

The B-24 Liberator was designed by the Consolidated Aircraft Corporation to meet the requirements of the USAAF for a four-engine heavy high-altitude long-range daylight bomber (for a comprehensive description of the B-24's characteristics and capabilities, I recommend The B-24 Liberator & Its Crew). The requirements of the Carpetbagger missions were decidedly different from the ongoing B-24 bombing strikes over Germany and included significant alterations to both the aircraft and the crew performance.

As the B-24s arrived at Harrington, some were already painted the black color that would become a defining characteristic of all Carpetbagger aircraft in order to make them less visible for night operations. In addition, a number of alterations were made to the B-24s in order to make them more capable for low-altitude nocturnal missions dropping not only supplies to Resistance groups, but also special agents (both men and women) trained for covert operations in occupied countries throughout the European theater.

"Converting to nocturnal special duty specification from daylight long-range bomber configuration was enough to tax even the most hardened of ground crew personnel. Ball turrets had to be removed and replaced with cargo hatches, nicknamed ‘Joe Holes’, through which the secret agents or ‘Joes’ dropped. A static line was installed for them and to facilitate bale outs, the hole had a metal shroud inside the opening. If the Liberator did not have a ball turret, a hole was made there. Plywood was used to cover the floors and blackout curtains graced the waist windows and navigator’s compartment, while blister side windows had to be installed to give the pilots greater visibility. Later models had their nose turrets removed. A ‘greenhouse’ was fashioned instead to allow the bombardier a good view of the drop zone and to enable him to carry out pilotage for the navigator. Suppressors or flame dampers were fitted to the engine exhausts to stifle the tell-tale blue exhaust flames. Machine-guns located on both sides of the waist were removed, leaving only the top and rear turrets for protection. In flight the entire aircraft would be blacked out except for a small light in the navigator’s compartment.

Oxygen equipment would not be needed at the low levels flown and was removed. A variety of special navigational equipment and radar aids had to be installed. The air crews learned that during the non-moon period, flights at night would be made with the use of Rebecca and an absolute radio altimeter. By means of all this equipment, the percentage of accuracy on a drop could be even greater than with ordinary visual pilotage.

Rebecca was a British radar directional, air to ground device which was originally fitted to aircraft in the RAF Special Duties squadrons. It was used to record impulses or ‘blips’ on a grid and directed the navigator to the ground operator. By varying the intensity or frequency of the blip, the ground operator (whose set was known as Eureka O) could transmit a signal letter to the aircraft. These signals could be activated from up to seventy miles away to enable the aircraft crew to pin-point its drop zone. Eureka sets, which weighed up to 100 lb, were parachuted in to Resistance groups. However, many Joes and Resistance radio-operators, not wishing to lug the set, which was heavy, or run the risk of being caught with it in their possession, refused to use it."

Source: The Carpetbagger Project II

The original Carpetbagger B-24 aircraft were B-24D's transferred from the 22nd Anti-Submarine Squadron. The "D" models were already configured with the "greenhouse" nose (Figure 13) alluded to in the above quote; which made them more amenable to anti-submarine operation by providing the bombardier with a better view of the ocean surface. This feature was adapted to later model Carpetbagger aircraft (e.g., the B-24H's of the 492nd) for same purpose, i.e., to give the bombardier a better view of the ground surface for low-level flight navigation and spotting the drop zone. This was especially important in the early stages of the Carpetbagger Operations, before the Rebecca radar systems were implemented, and drop zones had to be illuminated with secret flashlight signals.

Another important adaptation was replacing the Liberators' bomb shackles (used to suspend bombs in the bomb bay) in order to conform to the British-style suspension lugs that were attached to the "C containers" - cylindrical containers the British used to pack and parachute supplies into the drop zone. The containers could then be loaded into the B-24's bomb racks and released in the same manner as dropping bombs.

From a pilot's perspective, the low-level nocturnal nature of the Carpetbagger missions involved very different flight parameters and tactics from the high-altitude, daylight bombing missions the B-24 was designed for. A few days after arriving at RAF Tempsford in January of 1944, the initial US flyers began receiving instructions from the British RAF airmen and SOE personnel who were stationed there and had been conducting low level air drops in the European theater for many months.

One important lesson taught by the SOE staff was the need to memorise the route to the drop zone.

RAF pilots learned to literally map read their way by moonlight, memorising landmarks – the most successful pilot sometimes spent hours studying the route. However the B-24s were fitted with the best possible flying and navigational instruments. The most important flying instrument was a radio altimeter giving an accurate height readout on the low level flights. A Mark V drift sight was fitted in the navigators compartment which was moved into the forward section near to the nose.

The route to the drop zone was achieved by a team effort, the bombardier sat in the glazed nose on a swivel seat reading off landmarks to the navigator sitting at his table behind the blackout curtains. The pilot was provided with large blister windows giving a good downward view of the ground.

First radio navigation aid to be used on a mission was the Gee set, this recorded directional signals which were marked on a special chart – accurate within a quarter of a mile over England, but prone to jamming over enemy territory. The Rebecca / Eureka directional system consisted of a ground beacon (Eureka) set up on the drop zone, this was triggered by a signal from Rebecca set in the aircraft. Eureka then automatically sent out signals which were picked up by a calibrated receiver, this indicated the aircraft’s position in relation to the drop zone.

To avoid action with the enemy flights were ordinarily made at night and at low level. When it was necessary for an aircraft to cross enemy held areas equipped with anti-aircraft defences, a route was chosen which would expose the aircraft to the fire of light guns only. Thus the altitude attained seldom exceeded 7,000 feet. As soon as a dangerous area was passed the aeroplane dropped down to 2,000 feet or lower. A low altitude made it more difficult for the enemy to detect the aircraft either by sound or by radar detection devices. Obstacles on the ground distort the sound of a low flying aircraft far more than they do the noise of a high flying one, because of the sharper angles of sound reflection. Radar and sound detection devices had less time in which to focus on a low flying aeroplane, and the range of effective detection was shorter at low altitudes.

In order that accurate drops may be made, pilots endeavoured to get down to within 400 to 600 feet of the ground and to reduce their flying speed to 130 miles per hour or less. The low speed reduced the chances of damage to parachutes, as the shock of opening is much less at the slower speed. Personnel were normally dropped from a height of 600 ft with containers and packages being dropped from 300 – 500 ft.

Non moon period flights at night were made with the use of special navigation equipment: “Rebecca”; S-Phone and radio altimeter. By means of this equipment, the percentage of accuracy could be even greater than with ordinary visual pilotage, but reception parties had to have the ground counterparts of the S- Phone and Rebecca equipment and be able to use them expertly – something which was very difficult in territory occupied by the enemy. Thus, even in the dark periods, aircraft could fly low altitudes with only a slight increase in risk. However dark period operations were possible without S-Phone or Rebecca provided that the reception signals consisted of bonfires and provided there could be reference to prominent land marks which could be distinguished accurately in the dark, such as large rivers and lakes.

Source: Harrington Aviation Museum Northhamptonshire

Logistics

To provide the Carpetbagger missions with the equipment storage capacity and load preparation functions needed for supplies, weapons, and special agents to be delivered to Resistance groups in occupied countries, an OSS packing, storage, and coordination facility was established at Holmewood, a sixteenth-century estate near the village of Holme. In addition to the relatively close proximity to Harrington (35 miles to the west), the Holmewood location (code named Area H) was chosen because it was also nearby to an existing SOE packing station at St. Neots (20 miles to the south) that provided additional storage capacity and packing capabilities. Holme also had an advantage in that it was near to the London Edinburgh rail line and the Great North Road (A1). The following video describes early Carpetbagger operations at Area H that were focused primarily on supporting the French underground. These same operations were later expanded to support resistance efforts in other German-occupied countries throughout the European theater (e.g., Denmark and Norway).

"The OSS logistics effort at Area H was an unqualified success. During 1944, Area H packed 50,162 containers for air delivery by the RAF and the USAAF. In the first nine-months of 1944, this included more than 75,000 small arms and 35,000 grenades. Area H provided 96 tons of supplies to Belgium, 9 to Denmark, 3,055 to France, 119 to Poland, and 56 to Norway. Operations in 1945 in Denmark and Norway raised the total tonnage supplied."

Source: Supplying the ResistanceThe Norwegian Resistance

Invasion of Norway

In 1939, both Britain and Germany were viewing Scandinavia as strategic to any future conflict. The British were contemplating a shipping blockade to disrupt critical Swedish iron ore shipments to Germany from the Norwegian port of Narvik. Meanwhile the German Navy, fearful of that disruption, began arguing that seizing of potential British bases, and indeed the entirety of Norway, before the United Kingdom could act would protect iron ore shipments and allow the Norwegian coast to be used for staging submarine operations against the United Kingdom.

In November of 1939, Winston Churchill, then a new member of the British War Cabinet, proposed a plan to mine Norwegian waters in order to blockade the flow of iron ore transport ships, but the plan was rejected by the British leadership. After the start of the Winter War between The Soviet Union and Finland, the United Kindom and France began developing a plan to send aid to Finland. This required occupying Narvik and controlling the main railway used to transport iron ore from Sweden. The plan would also allow Allied forces to gain control of the Swedish iron ore mining district. However, the plan required the permission of Norway and Sweden which was denied after both countries received a stern warning from Germany. In addition, the justification for the action was removed when Finland sued for peace with the Soviet Union in March of 1940.

Meanwhile Hitler, convinced of the threat to Germany's iron ore supply, gave the go-ahead to develop a plan for the invasion of Norway and Denmark (considered important as a staging area for the Norway invasion and naval operations in the Baltic Sea). The resulting Operation Weserübung called for the rapid capture of the kings of Denmark and Norway, the occupation of the Norwegian capital Oslo, and occupation of nearby population centers, Bergen, Narvik, Tromso, Trondheim, Kristiansand, and Stavanger.

The German invasion began on 9 April, 1940. In a meeting scheduled that day the German ambassador to Denmark informed the Danish Foreign Minister that German troops were moving to occupy Denmark to protect the country from a Franco-British attack. In the face of an overwhelming opposition force and under the threat of Luftwaffe bombing the civilian population of Copenhagen, the Danish king and government capitulated 6 hours after the beginning of the invasion in exchange for retaining political independence in domestic matters.

The concurrent invasion of Norway began on 8 April. The Norwegian military was facing a vastly larger German order of battle: six infantry divisions, and a naval flotilla comprised of two battleships, 3 heavy cruisers, 5 light cruisers, 14 destroyers, 20 torpedo boats, 12 minesweepers, and numerous support vessels. The timeline of the invasion was as follows:

- Late in the evening of 8 April 1940, Kampfgruppe 5 [naval and infantry attack group headed toward Oslo] was spotted by the Norwegian guard vessel Pol III. Pol III was fired at; her captain Leif Welding-Olsen became the first Norwegian killed in action during the invasion.

- German ships sailed up the Oslofjord leading to the Norwegian capital, reaching the Drøbak Narrows (Drøbaksundet). In the early morning of 9 April, the gunners at Oscarsborg Fortress fired on the leading ship [of Kampfgruppe 5], Blücher, which had been illuminated by spotlights at about 04:15. Two of the guns used were the 48-year-old German Krupp guns (nicknamed Moses and Aron) of 280 mm (11 in) calibre. Within two hours, the badly damaged ship, unable to manoeuvre in the narrow fjord from multiple artillery and torpedo hits, sank with very heavy loss of life totalling 600–1,000 men.

- The now obvious threat from the fortress (and the mistaken belief that mines had contributed to the sinking) delayed the rest of the naval invasion group long enough for the Royal Family, the Cabinet and members of Parliament to be evacuated, along with the national treasury. On their flight northward by special train, the court encountered the Battle of Midtskogen [German raiding party attempting to capture King Haakon, turned back by Royal Guards] and bombs at Elverum and Nybergsund. As the Norwegian king and his legitimate government were not captured, Norway never surrendered in a legal sense to the Germans, leaving the Quisling [Vidkun Quisling, facist Nazi collaborator] government illegitimate. The Norwegian government-in-exile based in London remained, therefore, an Allied nation in the war.

- German airborne troops landed at Oslo airport Fornebu, Kristiansand airport Kjevik, and Sola Air Station - the latter constituting the first opposed paratrooper attack in history; coincidentally, among the Luftwaffe pilots landing at Kjevik was Reinhard Heydrich [one of the main architects of the Holocaust].

- Vidkun Quisling's radio-effected coup d'etat at 7.30pm on 9 April - another first.

- At 8.30pm the destroyer 'Æger' is attacked and sunk outside Stavanger by ten Junkers Ju 88 bombers, after it sunk the German cargoship 'MS Roda'. Roda was a carrying a concealed ammunition and weapons cargo.

- Cities/towns Bergen, Stavanger, Egersund, Kristiansand, Arendal, Horten, Trondheim and Narvik attacked and occupied within 24 hours.

- Heroic, but wholly ineffective, stand by the Norwegian armoured coastal defence ships Norge and Eidsvold at Narvik. Both ships torpedoed and sunk with great loss of life.

- First Battle of Narvik (Royal Navy vs Kriegsmarine) on 9 April.

- The German force took Narvik and landed the 2,000 mountain infantry, but a British naval counter-attack by the modernised battleship HMS Warspite and a flotilla of destroyers over several days succeeded in sinking all ten German destroyers once they ran out of fuel and ammunition.

- Devastating bombing of towns Nybergsund, Elverum, Åndalsnes, Molde, Kristiansund N, Steinkjer, Namsos, Bodø, Narvik - some of them tactically bombed, some terror-bombed.

- Main German land campaign northward from Oslo with superior equipment; Norwegian soldiers with turn-of-the-century weapons, along with some British and French troops (see Namsos Campaign), stop invaders for a time before yielding - first land combat action between British Army and Wehrmacht in World War II.

- Second Naval Battle of Narvik (Royal Navy vs Kriegsmarine) on 13 April.

- Land battles at Narvik: Norwegian and Allied (French and Polish) forces under General Carl Gustav Fleischer achieve the first major tactical victory against the Wehrmacht in WWII, and the following withdrawal of the Allied forces (mentioned below); Fighting at Gratangen.

- With the evacuation of the King and the Cabinet Nygaardsvold from Molde to Tromsø on 29 April, and the allied evacuation of Åndalsnes on 1 May, resistance in Southern Norway comes to an end.

- The "last stand": Hegra Fortress (Ingstadkleiven Fort) resisted German attacks until 5 May - of Allied propaganda importance, like Narvik.

- King Haakon, Crown Prince Olav, and the Cabinet Nygaardsvold left from Tromsø 7 June (aboard the British cruiser HMS Devonshire, bound for Britain) to represent Norway in exile (King returned to Oslo exact same date five years later); Crown Princess Märtha and children, denied asylum in her native Sweden, later left from Petsamo, Finland, to live in exile in the United States.

- The Norwegian Army in mainland Norway capitulated (though the Royal Norwegian Navy and other armed forces continued fighting the Germans abroad and at home until the German capitulation on 8 May 1945) on 10 June 1940, two months after Wesertag [first day of the invasion], that made Norway the occupied country that had withstood a German invasion for the longest time before succumbing.

The planning for the German assault on Denmark and Norway did not include Sweden because that country was already surrounded by territory in control of the Germans on the north and west (Norway), and the south (the Baltic Sea). On the east was Finland, controlled by the Soviet Union, then on friendly terms with Hitler under the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact. So Sweden, the country that would provide refuge for Lt Keeney and other members of his crew after their escape from Norway, remained neutral throughout the war.

Rise of the Resistance

Even as German troops were arriving in Norway to begin the invasion, the German representative in Oslo issued a demand that Norway accept the "protection of the Reich", to which the Norwegian foreign minister replied "We will not submit voluntarily; the struggle is already underway."

As described above, in anticipation of the German effort to capture the government, the king and royal family, the entire Norwegian parliament, and the cabinet evacuated from Oslo and eventually established a government in exile in Great Britain. This served to undermine the legitimacy of the German collaborator Vidkun Quisling's attempt to claim the Norwegian government for himself via a coup d'etat.

In opposing the invasion, the Norwegian military was at a distinct disadvantage because of its smaller size and because a movement toward disarmament had taken place in Norway at the end of World War I, leaving the Norwegian military largely underfunded and weakened in the spring of 1940. The sinking of the German heavy cruiser Blücher at the beginning of the conflict as well as spirited defenses of some locations in southern Norway set in motion the creation of a number of military operations that then morphed into an underground resistance movement that persisted throughout the remainder of the war.

The Milorg (military organization), after starting as a small sabotage unit, evolved into the main Norwegian resistance organization. In close cooperation with the British Special Operations Executive (SOE), Milorg's work included intelligence gathering, sabotage, supply-missions, raids, espionage, transport of goods imported into the country, release of Norwegian prisoners, escort for citizens fleeing the border to neutral Sweden, and assisting in the escape, evasion, and rescue of Allied air crews shot down over Norway.

Following the German occupation in April 1940, Milorg was formed in May 1941 as a way of organizing the various groups that wanted to participate in an internal military resistance. At first, Milorg was not well coordinated with the Special Operations Executive (SOE), the British organization to plan and lead resistance in occupied countries. In November 1941 the Milorg became integrated with the High Command of the Norwegian government in exile in London, answering to Department FO. IV, which dealt with sabotage operations, but its British counterpart, SOE, was still operating independently. This lack of coordination led to a number of tragic incidents, creating bitterness within Milorg. SOE changed its policy at the end of 1942, and from then on Milorg and SOE efforts were coordinated.

Milorg was organised into a council and 14 districts. District 13 was the Oslo region. Mainly for fear of retaliation, like the Telavåg tragedy, Milorg kept a low profile at first. But they became more active as the war progressed, especially when Jens Christian Hauge became leader of Milorg. At the time of the German capitulation on 8 May 1945, Milorg had been able to train and supply 40,000 soldiers. They also played an important part in stabilizing the country at this crucial point.

Source: Military-Wiki

Following is a pictorial history of the Milorg, given to Ralph Keeney by former members of the Norwegian underground when he visited Norway after the war.

Tiger's Revenge

The Aircraft

The B-24 aircraft (S/N 42-94816) named Tiger's Revenge made its debut as a member of the 489th Bombardment Group, 846th Bombardment Squadron. The 489th was stationed at RAF Halesworth, Suffolk, England between April and November of 1944. During that period the 489th group flew 106 combat missions, losing twenty-six aircaft.

After the 489th's final mission on 10 November 1944, the group was redeployed to the US to train for the Pacific theater. A number of the 489th's aircraft were reassigned to other groups in the 8th Air Force, including Tiger's Revenge, which first showed up in the 492nd inventory on 6 Feb 1945 as a B-24H. (The original Carpetbagger aircraft were earlier model B-24Ds transferred from the 22nd Anti-Submarine Squadron.) Tiger's Revenge appears in the 492nd's Operations Log for the first time as having flown a night bombing mission on a 20/21 Feb 1945. That date corresponds to night bombing missions flown in Germany on 20 & 21 Feb 1945 as listed in the Keeney crew missions log (Figure 26 below).

A subsequent 6 Mar 1945 492nd inventory lists Tiger's Revenge as a B-24H NB. The "NB" likely stands for night bomber. That inventory also indicated that the aircraft was detailed to another facility, possibly undergoing repairs or a refit. A later inventory on 6 Apr 1945 lists Tiger's Revenge as a B-24H SH NB. The "SH" designation specifies that the H2X blind bombing radar (code-named "Mickey") had been retrofitted as an upgrade to the existing H2S radar in the B-24H, probably during the gap between Keeney crew missions seven (3 Mar 1945) and eight (7 Mar 1945). The H2X radar, used as ground imaging for navigation and bombing, enabled a much higher resolution of the terrain below the aircraft and was particularly adept in overcast weather conditions and night bombing. It implemented a higher frequency band which degraded the ability of the Luftwaffe to detect the radar emissions and locate the bomber (the lower H2S freqency had been compromised by the Germans earlier in the war).

The H2X on later B-24 Liberators also replaced the ball turret, being made retractable as the ball turret was for landing on the Liberator. The operators panel was installed on the flight deck behind the co-pilot (where the radio operator's normal position was). In combat areas the Mickey operator directed the pilot on headings to be taken, and on the bomb run directed the airplane in coordination with the bombardier. The first use of Mickey was against Ploiești on April 5, 1944.

Source: WikipediaThere are several factors that indicate that Tiger's Revenge was not outfitted with all the modifications characteristic of Carpetbagger aircraft: 1) The H2X radome replaced the B-24s ball turret. The ball turret was the location for the "joe hole", so Tiger's Revenge did not possess a joe hole (this was confirmed in a letter from Arthur Greenwood to Magne Hvilen), 2) as shown in Figure 21, Tiger's Revenge was not retrofitted with the "greenhouse" nose but rather retained the B-24H redesigned bombardier compartment with glazed three-panel bombsight window and the forward-looking nose turret guns (.50 cal w/flash suppressors for night work) above the bombardier's position, 3) the inventory information indicates that Tiger's Revenge was never assigned the "B-24HSA" designation indicative of full Carpetbagger modifications, and 4) 13 out of the 21 missions flown by the Keeney crew (see Figure 26 below), were bombing missions, including the first seven.

The Crew

As documented above, Lt. Keeney's last duty station in the course of his formal pilot training was Tonopah Army Air Field, Tonopah, Nevada where he was joined, for combat crew training, by the other nine members assigned to what would become the Tiger's Revenge crew. By that time, each of the crew members had completed their own training regimes as exemplified by Tail Gunner Art Greenwood's experience: "... I started at Fort Meade, Maryland; took basic training at Miami Beach, Florida, from Essex House Hotel at 10th Collins Blvd; took gunnery training in Harlingen, Texas; then to Hammer Field [gunnery ranges] in Fresno California; more training with a full crew at Tonopah, Nevada ..."

Top Row left to right:

- Ralph Keeney - Pilot

- Hayden Parker - Co-Pilot

- Jack Devine - Navigator

- Steve Marangas - Bombardier

Bottom Row left to right:

- Pete Brabec - Radio Man

- Claude McClure - Armorer / Waste Gunner

- Bob Beard - Assistant Engineer / Nose Gunner

- Eugene Hagaman - Waist Gunner (had sinus problem and was dropped from crew) *

- Arthur Greenwood - Tail Gunner / Assistant Armorer (youngest member, 18 yrs old)

- Bob Broadus - Engineer / Top Turret Gunner

* Ralph Maassen replaced Eugene Hagaman as Waist Gunner.

Ralph Maassen

The Keeney crew is shown in Figure 23. As noted, Eugene Hagaman was replaced by Ralph Maassen when Hagaman was not able to tolerate high altitude flights during training exercises (pain and ruptured blood vessels). Claude McClure was trained to operate a Sperry Ball Gun as the Ball Turret Gunner but the Ball Turret had been replaced by the H2X radar in Tiger's Revenge, so he served as the second Waste Gunner in addition to his Armorer responsibilities. I don't have conclusive information as to who was the Top Turret Gunner but that is a position that was usually assigned to the Engineer (Figures 24 & 25).

The Missions

The missions flown by the Tiger's Revenge crew during their time at RAF Harrington are listed in Figure 26. The locations shown in the annotated listing with square brackets, [ ], were garnered from various interviews and writings of the crew members and are as accurate as I could determine them. All of the missions were flown at night.

Missions:

- 1. 20 Feb 45: Bombing - Germany [Neustadt]

- 2. 21 Feb 45: Bombing - Germany [Duisburg]

- 3. 23 Feb 24: Bombing - Germany [Dusseldorf]

- 4. 29 Sep 44: Gas supply to Allied forces (General Patton's tanks) in France [Lille] (date out of order)

- 5. 30 Sep 44: Gas supply to Allied forces (General Patton's tanks) in France [St. Quentin] (date out of order)

- 6. 29 Feb 45: Bombing - Germany [Wilhelmshaven]

- 7. 3 Mar 45: Bombing - Germany [Dortmund]

- 8. 7 Mar 45: Bombing - Germany [Dortmund]

- 9. 8 Mar 45: Bombing - Germany [Emden]

- 10. 20 Mar 45: Carpetbagger - Denmark [Strandby]

- 11. 23 Mar 45: Carpetbagger - Denmark [Sejerslev]

- 12. 24 Mar 45: Carpetbagger - Denmark [Skaar]

- 13. 26 Mar 45: Carpetbagger - Denmark [Auning]

- 14. 5 Apr 45: Bombing - Germany [Travemunde]

- 15. 6 Apr 45: Bombing - Germany [Stade]

- 16. 10 Apr 45: Bombing - Dessau, Germany

- 17. 13 Apr 45: Bombing - Boizenburg, Germany

- 18. 14 Apr 45: Bombing - Neuruppin, Germany

- 19. 16 Apr 45: Bombing - Lechfeld, Germany

- 20. 19 Apr 45: Carpetbagger - Norway [Sveindal]

- 21. 20 Apr 45: Carpetbagger - Norway [Granheim] (shot down - last mission flown)

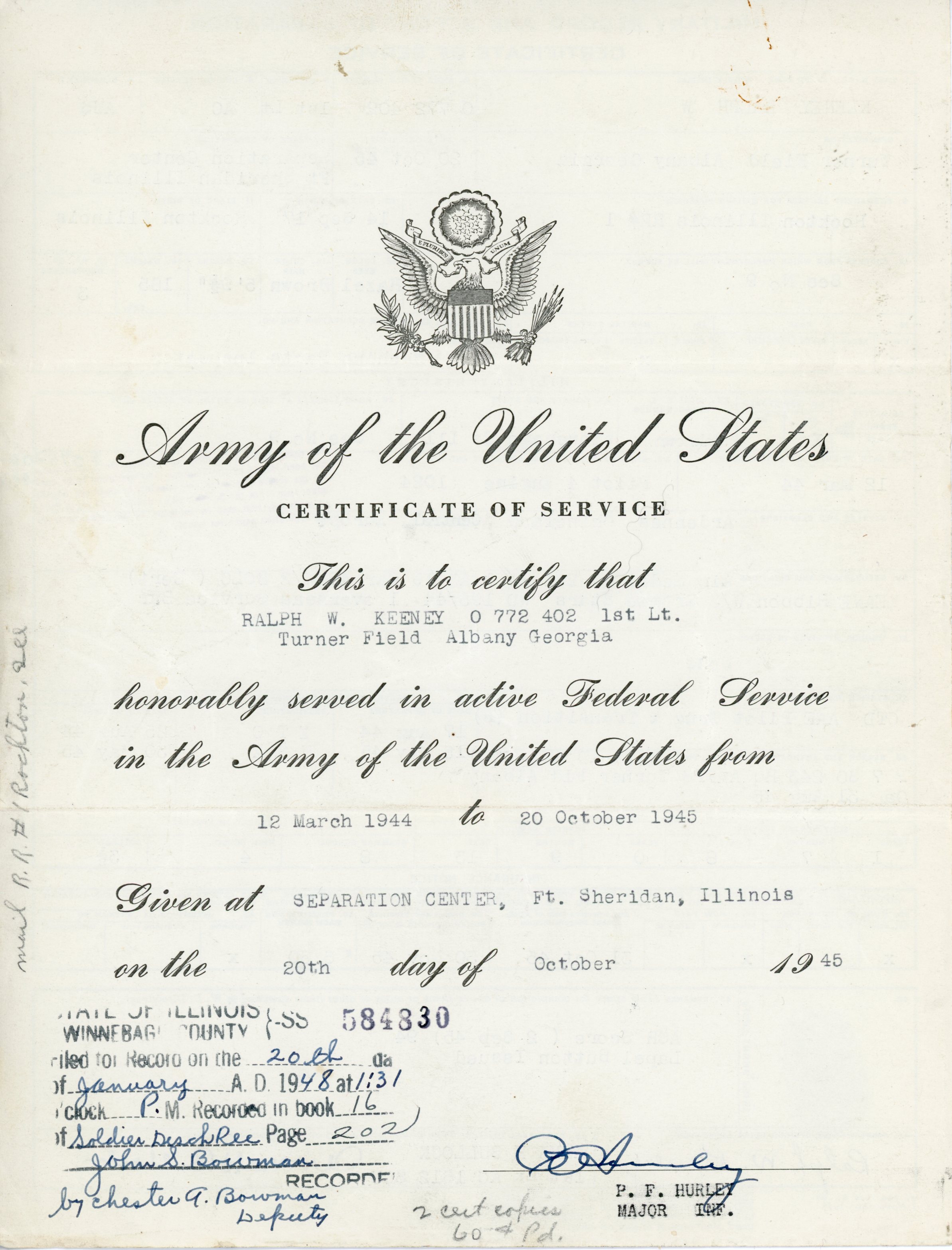

On March 18, 1945, after having piloted Tiger's Revenge for seven combat missions, Ralph was promoted to 1st Lt. (Figure 27). His recomendation for promotion read as follows: ""Subject officer has clearly demonstrated his fitness for promotion by outstanding performance of duty in actual combat during the period in which he has held his present grade. The officer concerned is presently occupying a combat position vacancy, having completed seven missions. The date of his last mission is 9 March 1945. The circumstances involved in this case are in fact exceptional." The reference to "occupying a combat position vacancy" likely refers to the bombing missions flown by Tiger's Revenge which were outside of the Carpetbagger objectives. "Seven missions" refers to the seven bombing missions listed in Figure 26 flown by Tiger's Revenge between 20 February 1945 and March 8/9 1945.

In a brief history of his World War II experience, Arthur Greenwood described some of the activities and missions flown by the Tiger's Revenge crew leading up to the last mission:

Not having an immediate assignment, we trained some more night flying by mock-bombing London which was a scary experience. Especially, if the anti-aircraft gunners (mostly women) got trigger-happy. Their radar equipped lights didn't have to search the sky for enemy aircraft, the radar searchlight was just turned on and it was on you. You were looking down a blue shaft of light while, in turn, several other search lights homed in on you until you could read a newspaper in the plane. After you were identified, all the search lights would turn off. Amazing experience!

While all this was going on, we noticed a lot of activity of British planes and personnel visting us. Mosquito bombers, Spitfires and ranking British officers. Our curiosity was satisfied one day when we had a briefing at operations for all air crews.

Along with our usual American squadron commanders, we had a host of RAF top-brass along with them. When we learned what our mission was to be, you could have heard a pin drop! We were to fly diversion in conjunction with the Royal Air Force.

While we were preparing to initiate this plan, we bombed pill boxes containing German Wehrmacht in France that the advancing Allied Forces had passed up; hauled gasoline to General Patton's tanks in Lille and St. Quentin, France; dropped French Maquis underground personnel, supplies and French invasion Franc's to the Allied Forces. And, eventually, did the same thing for Denmark and Norway.

When we flew diversion for the Royal Air Force, the 492nd Bomb Group would precede on a course toward a designated target, throwing alluminum foil (strips) to attract German radar. Later on, the main RAF bomb Groups would follow in our path, but at a specific time divert to their INTENDED target. For example: Cologne, Dusseldorf, etc.

By the time the Luftwaffe discovered the ruse, the RAF had dropped their bombs and were heading home without losing a plane. This worked only for two or three raids, but was effective.

British bombers were made up of Lancastars and Halifaxes. The Lancaster carried the 10-ton "Blockbuster". This bomb was so large that the planes couldn't close their bomb bay doors. It was quite a treat to witness them following us over the white cliffs of Dover in the setting sun.

When we started supplying the Danish and Norwegian underground with their needs, we had to be fully armed as we had no fighter escort. Our black colored planes were almost undetectable in the night skies, but this didn't make us invisible.

On one flight to Denmark, we got the correct code from the Danes in the drop zone, but we noticed an exchange of gunfire on the ground and decided not to drop. Instead, we headed back to England. We crossed a railroad track while just a few hundred feet off the ground and we were fired upon by German soldiers riding on a flatcar. Being taken by surprise, my gunsight light was not on. However, I was able to train my guns on the attackers and get enough hits through watching the tracers and armor-piercing incendiaries exploding on contact. Just like spraying with a water hose!

We didn't get off scott-free, as the German ambush on the railroad flatcar hit our no. 1 engine and we had to feather it. Flying across the channel on three engines with a full load gave us some thought as to what our landing back at the base held in store. Our pilot having experienced one other crash back in Tonopah, Nevada, gave him confidence through experience he needed and we landed safely.

Source: "Air Corps Career Account" attached to letter from Arthur Greenwood to Magne Hvilen, June 30, 2007On April 2, 1945, after the Tiger's Revenge crew had flown their initial four Carpetbagger missions, Lt. Keeney was awarded an Oak Leaf Cluster for wear with the previously awarded Air Medal (Figure 29).

The Last Mission

In the late evening hours of April 20, 1945, Tiger's Revenge took off from RAF Harrington on a mission to supply a Norwegian Milorg base northwest of Oslo. After crossing the North Sea at an altitude of 1,000 ft., the B-24 began to climb and crossed the coast heading northward toward the objective. About 12 to 15 miles inside the coast, near the town of Risør, it was attacked by a Messerschmitt 110 or a Junker JU-88 night fighter * which, in the words of the the B-24 pilots, "did a good job" (Luftwaffe aircraft were known to have been stationed at Kjevik, about 50 miles south of Risør along the Norwegian coast). According to a later intelligence debrief, the navigator, Lt. Jack Devine, ".. felt the plane shudder. He thought it had been hit by flak, but then, looking down, he saw an ME-110 below the B-24. The B-24 turned in attempt to escape, but it was losing gasoline rapidly. A large hole had been knocked in the main gasoline tank. No. 1 engine was hit and the flaps and aileron on the left side were shot out. The ME 110 stuck with the B-24 for ten minutes but it could not line up for another attack. The pilot decided to try to reach Sweden. Besides the damage to No 1 engine and to the left wing, a large hole had been ripped between the right wing and the fuselage; and the inter-phone system was shot out."

The Final Flight Path

Although the night fighter broke off the attack, Lt. Keeney realized that the B-24 was no longer capable of completing the mission, and ordered the load to be jettisoned before attempting to gain altitude and head east toward Sweden. According to the tail gunner, Art Greenwood, a water ditch was considered at one point but was rejected because the aircraft was too badly damaged, "aside from #1 engine being on fire; #2 was feathered; #3 was losing fuel profusely, and #4 was the only reliable engine we had." Soon, the damages to the aircraft's engines and control surfaces made it impossible for the pilot to maintain course, and the B-24 gradually drifted northward, eventually crossing the coastline near the Norwegian town of Stavern. At that point, intense anti-aircraft ground fire was encountered which rendered the aircraft virtually unflyable. The anti-aircraft fire likely emanated from guns stationed at the German-built Rakke fort, located south of Stavern. Miraculously, none of the crewmen were seriously injured by the night fighter attack or the subsequent anti-aircraft fire.

Once over land, with no ability to control the aircraft or gain altitude, Lt. Keeney gave the order to bailout. From Art Greenwood, "To add insult to injury, the intercom system wasn't working. I was fortunate enough to hear the co-pilot say to go on (wireless) command. Other members of the crew did not hear this, so I had to keep the ones informed of what the pilot planned to do. Which was to bailout! I got a very worried expression from the two waist gunners, but they prepared themselves."

Greenwood was the first to exit the aircraft (in the vicinity of Stavern),"As I stood with my parachute in place, straddling the open hatch waiting for the jump signal, ground anti-aircraft fire opened up and I just put my feet together and dropped. Needless to say, I couldn't wait for a signal."

The remaining flight path of Tiger's Revenge, once it crossed over Stavern, is the subject of some controversy. The initial portion of the path can be traced by the distribution of the crew member's bailout locations. As can be seen in Figure 33 below (yellow line) after Greenwood exited near Stavern, the aircraft drifted into a wide left turn and crossed over the Brunlanes region from east to west. The bailouts (with the possible exception of Keeney who was the last to bail out) took place along this east-west traverse. The bailout sequence after Greenwood, as inferred from the landing locations, was Parker, Beard (and possibly Devine whose bailout location was not well documented in my sources but was likely somewhere in the vicinity of Larvik), Brabac/Broaddus, and Maassen/McClure.

When Ralph Keeney's grandson Kevin Moore visited Norway in 2007, in addition to being given a tour by Magne Hvilen and his wife Kjetil, he learned of an ongoing debate over the nature of Tiger's Revenge's flight path after the next-to-last crew man had bailed out (Lt. Keeney being the last to bail). Kevin met a Norwegian gentleman named Hans Oddane who was involved in the debate and had done an analysis of Tiger Revenge's flight path leading up to the crash. His analysis was based in part on information provided by his brother and another individual who observed a "heavy aircraft" flying at a low altitude with flames coming from the "outer starboard engine" early in the morning of April 21, 1945. Here, in Hans Oddane's own words (and my very rough translation), is what these observers told him:

I have an older brother, Halvard. He watched air traffic over the country for days and many bright nights. Our family lived at the time in Nevlunghaven in a house for 20 years and we had a good view of the north east and west. On the night of April 21, 1945, he sits up for hours. That night there were more planes to look at heading North in higher Air Layers, 0125-0130. Then he sees from his window, a big plane, (heavy aircraft low level) at low altitude heading south-southwest towards Nevlunghavn. The plane is on the right turn and a loud engine sounded. The plane completes the turn. My brother rushes into the kitchen, opens the window to the west. He hears the roaring engine sound in the direction of Amli, Søndersrød [Søndersrød is a general locality in the Larvik Municipality and Amli is a farm located within the Søndersrød area about 1 1/4 miles north and slightly west of Nevlunghaven]. After a while, the sound diminishes, it lasts even a while. He registers dark smoke coming up in the north-north east direction of Halle and Sandene [Halle is a hamlet north of the Sandene farm (where Lt. Keeney's parachute came down) and the Eikelund farm (where Tiger's Revenge crashed - see Figure 33)].

Charles Rudskjar of Nevlunghavn, 18 years old, woke up by strong engine drive from the North. Quickly coming to the window in the west, he sees a large aircraft, in a right turn, very low. A visible flame stands out from the outer starboard engine. (Charles makes notes in his diary) (Halvard notes day book 1945.) Word of mouth spreads on the morning of 21 April. An American plane has crashed at Eikelund. My brother took his bike and went to the place. German guards were in place at the plane, not all the guards were paying close attention to the security. He got parts from the plane, some parts lay loose. A guy with several parts was chased several times. The next day comes an open German staff car with higher officers, they rise and look around and note that spectators have come too close. He gives the guards verbal lecture for poor watching, and being physically dull. Keep people away from the plane, explosion may occur from the wreckage. One of the officers steps on the wreckage from the wing, tears off the duct from the rudder, and extracted despicable paper [likely some sort of insignia]. The big question over the past years, was it Tiger's Revenge in the right turn that was seen over Nevlunghavn that night?

Shown below are diagrams of two possible final flight paths that Hans Oddane provided to Kevin Moore when Kevin visited Norway.

Figure 34 depicts an "Alternative B" flight path that Oddane drew to explain the observations made by his brother Halvard and Charles Rudskjar (this flight path is also depicted by the yellow line in Figure 33). After all but perhaps the Keeney bailout, the aircraft turns south and heads in the south-southwest direction as described by Halvard. Once past Nevlunhaven it completes a 180° right turn and heads back north which corresponds to Halvard and Rudskjar seeing an aircraft out to the west of Nevlunghaven and heading north toward Amli (annotated on Oaddan's diagram). Although he doesn't describe them in the narrative above, he included the names Anders Flekke and Sue "in Nordal" on his diagram, implying that they were also witnesses along the B-24's flight path toward it's eventual crash landing at Eikelund farm. The descriptions of the altitude and size of the aircraft, and the engine noise, visible flames from one engine, and subsequent smoke rising on the horizon in the direction of Halle (which is just north of Eikelund farm) certainly comport with what you would expect to see and hear from a badly damaged B-24 in a death spiral.

One important factor to consider in the flight path debate is the location (Figure 36) and timing of Lt. Keeney's bailout.

The close proximity of the crash site and Lt. Keeney's landing location implies that Ralph's bailout occurred very soon before the crash. If Lt. Keeney had bailed out somewhere along the loop around Nevlunghavn as shown in Oddane's Alternative B, it would be highly unlikely that these two locations would be so close to one another. This appears to be why Hans annotated "Pilot in airplane?" at several locations along the Alternative B flight path and why he chose to diagram a downward spiral around the area of the Eikelund farm/Sandene house. The scenario being that Lt. Keeney remained in Tiger's Revenge, perhaps attempting to direct the aircraft to crash in an uninhabited area before bailing out. Once the aircraft began it's final death spiral, he had no choice but to jump before his bailout minimum was reached. The spiral would account for the aircraft coming back around to crash nearby to Ralph's landing location (in accordance with both A and B alternatives). That possibility is inline with a conversation my son Kevin and I had with Ralph, in which he stated that he heard and saw the crash a very short time after he hit the ground. As can be seen in Figure 35, the direction of the B-24 at the time of the crash appears to be to the northeast as is reflected in both alternates.

Hans Oddane's "Alternative A" flight path is approximated in Figure 33 by the blue line by excluding the southern loop. It differs from Alternative B in that it either ignores the possibility that the witness accounts are valid evidence for a southern loop around Nevlunghavn, or it assumes that Halvard, Rudskjar, and other possible witnesses were either mistaken or that they had observed a different aircraft.

In summary, Alternative A discounts the observations made that night by Halvard, Rudskjar, and other possible witnesses. I have no reason to doubt those observations, as they correspond well to one another, and there is no evidence that a another large aircraft flying low and on fire was present in the area that night. Alternative B accounts for the witnesses' observations as well as the locations of the crash site and Ralph's landing. Therefore, even though there is no definitive data showing the actual flight path, I am more inclined to accept Alternative B as being closer to the truth of what happened in the final stages of Tiger Revenge's last flight. No doubt some of the Norwegians involved in the debate over the years since, would not agree with me.

A Missing Air Crew Report (Figure 38) was compiled shortly after Tiger's Revenge failed to return to Harrington after the April 20 mission. The report was later updated by hand after the statuses of the ten crew members were determined.

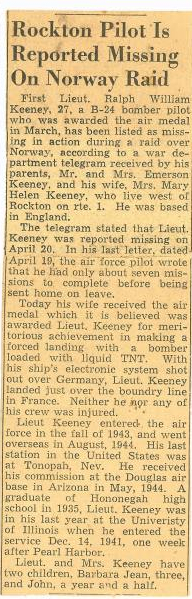

Soon after the crash and before the Secretary of War's office was aware of Lt. Keeney's rescue, a "missing in action" telegram was sent to his family in Rockton, Illinois (Figure 39). Turns out his mother was right!

Once the family had been notified, Lt. Keeney's status became the subject of the local news in his hometown (Figure 40).

The Rescue

Very early in the morning of April 21, 1945, Severin Sandene was made aware of the presence of a stranger who had dropped from the sky and landed outside his front door (Figure 41). That was the starting point for Ralph's rescue journey (Figure 33 - red line). Later, in a letter (dated October 29, 1945) to Ralph Keeney, Severin described the experience:

"Of course we got quite surprised and quite a shock when you landed outside our doors that night at 2 a.m. We understood at once that you belonged to one of our Allies, and started to think how we best could help you. Be sure, we would have liked to have kept you as our guest for awhile, but we expected the Germans would soon be looking for you, which also happened. Six armed Germans arrived at 4 a.m or about three quarters of an hour after you left and they kept everyone in the house. As a matter of fact my house was the first they searched. Everyone here was then in bed, except myself, and I firmly told them that they would not find any American in my house.

Do you remember my trousers you first tried on? The Germans were surprisingly interested in them. I don't understand why, but at last they left without finding anything. Olaf Holhjem who took you from here, arrived back while they were still searching. Fortunately he avoided to catch any suspicion. We had of course to send you to some in the Underground Movement who understood English, and the first man you came to was a teacher in English, a good Norwegian, but his nerves were on edges, and he didn't dare to help you. From there you were taken to a man by the name of Lillestølen, who with his family had been 6 years in the U.S.A. and whose son was a member of the Home Front."

The "man by the name of Lillestølen" was Pastor Robert Lillestølen, who lived on Gusland farm and who wrote the following narrative entitled, "American Airmen on a Short Visit to Brunlanes in Norway, 21, April 1945", describing his experience during the time that Lt Keeney was in his protection:

Brunlanes, Norway

Early one morning before the break of day, I suddenly woke up hearing somebody throwing stones at my window. Outside in the darkness I saw two men. One of them said: "I am Olaf Holhjem. I bring with me an American airman who has crashed with his aircraft. But I cannot speak English. Can you take care of him?" Brave Olaf Holhjem - he had walked quite alone with pilot Keeney for almost an hour over fields and through woods - where German soldiers could popup every minute - to seek for a person who could speak English and could help Captain Keeney to escape.