John Lester Cadman

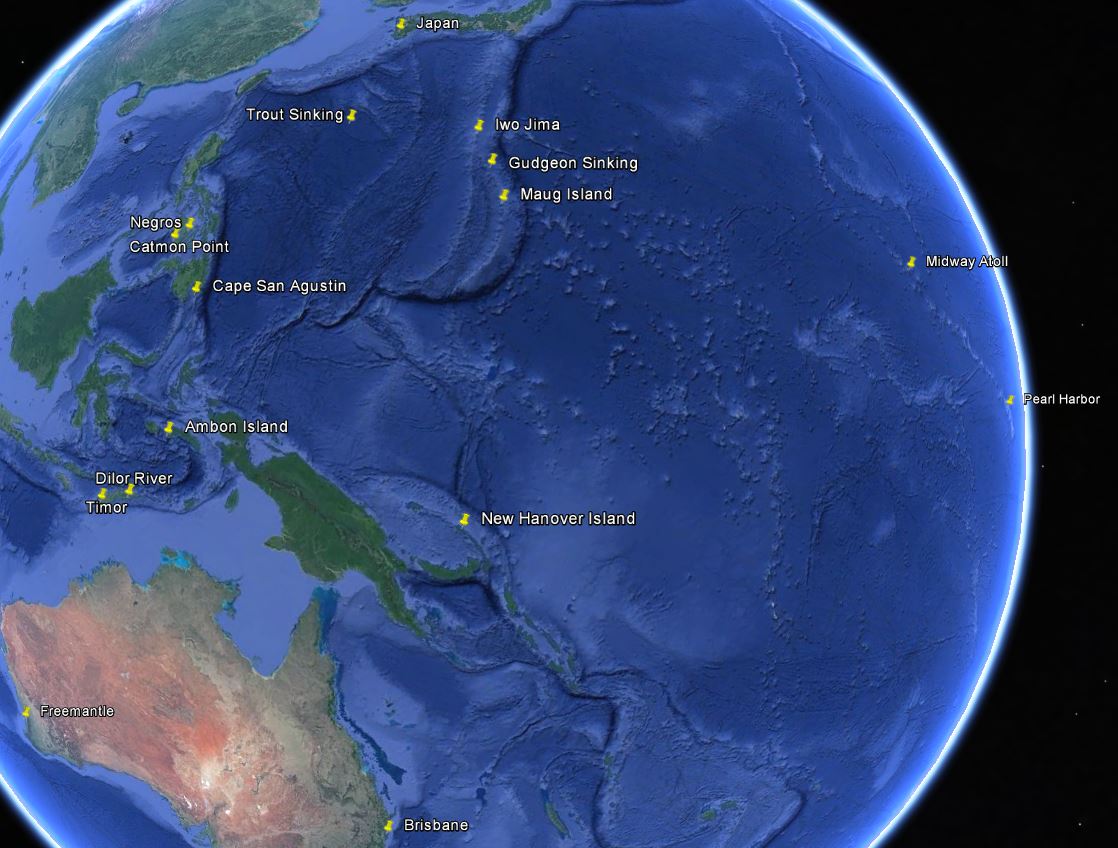

NAVAL WARFARE IN THE PACIFIC

There are no extraordinary men... just extraordinary circumstances that ordinary men are forced to deal with.

- Admiral William F Halsey

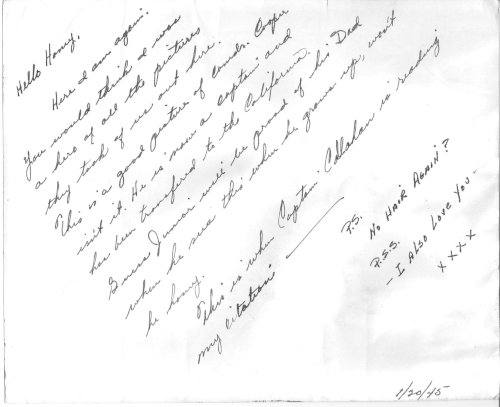

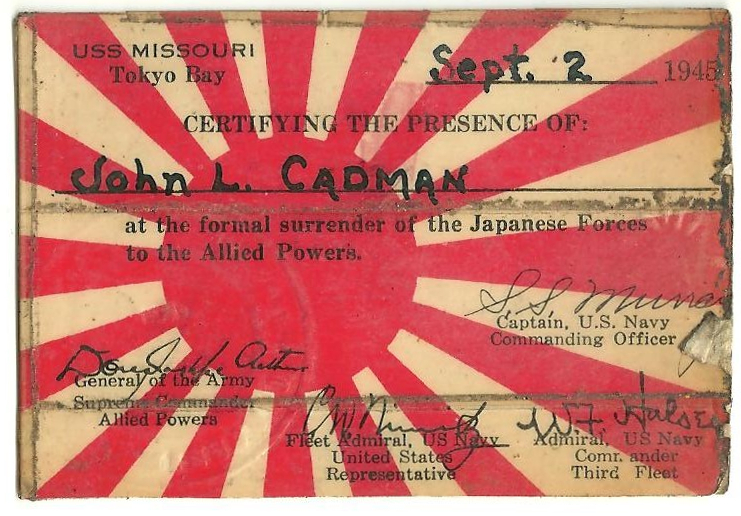

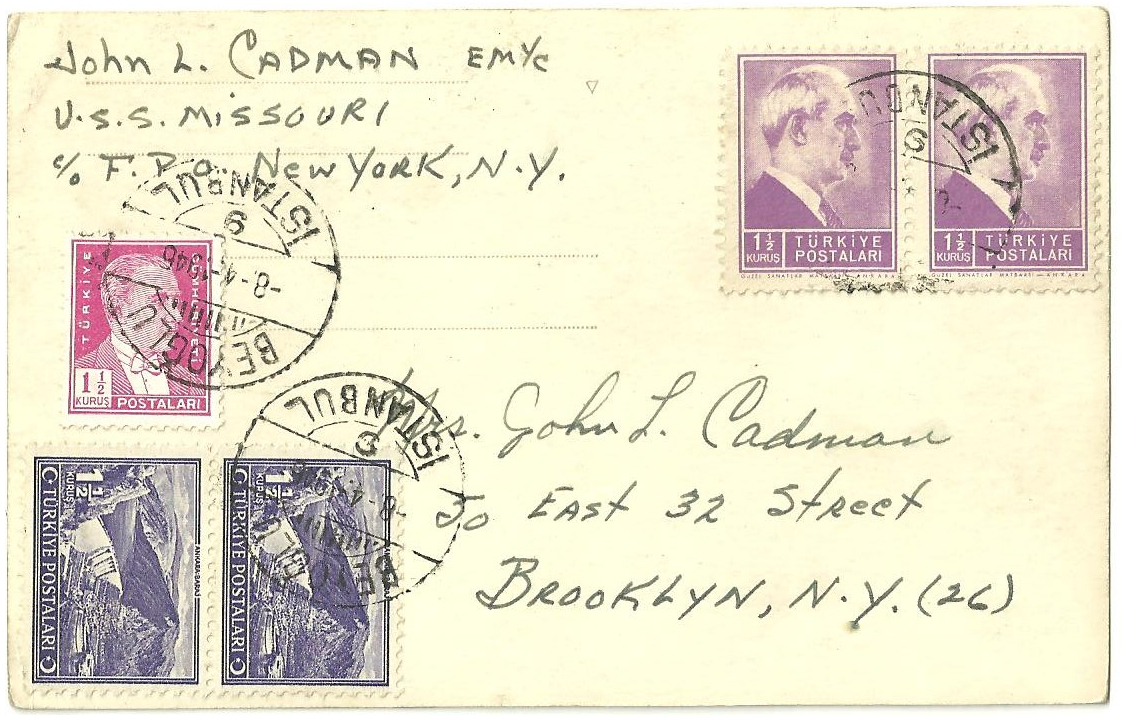

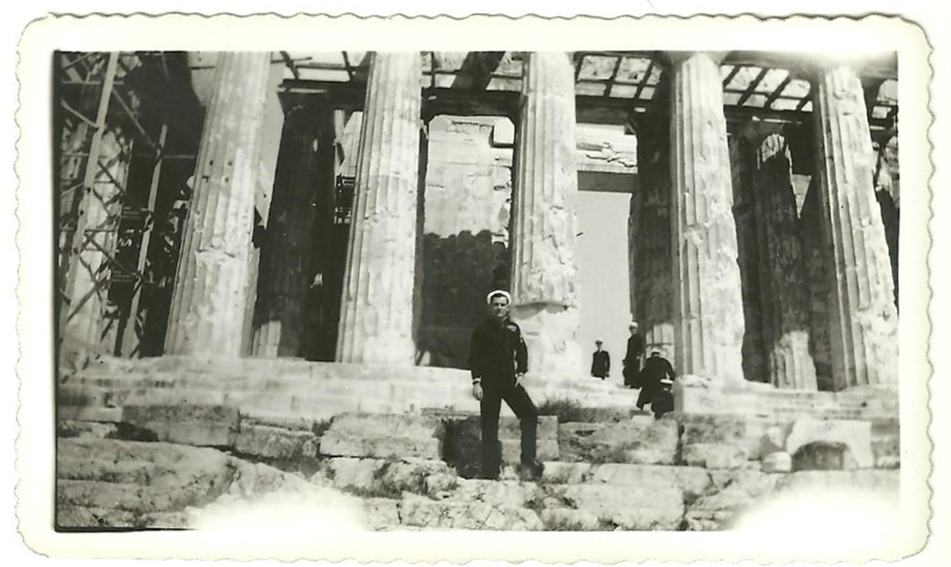

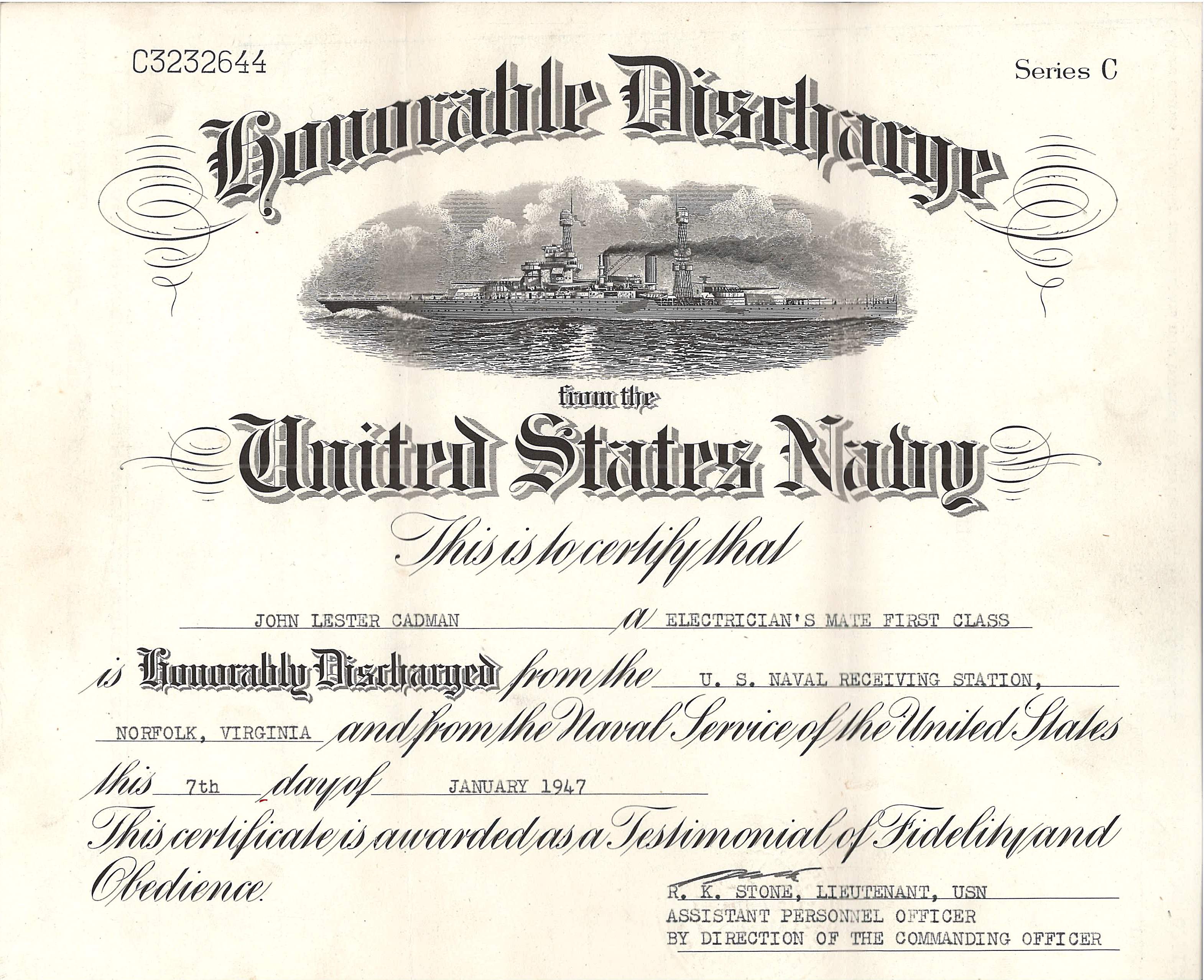

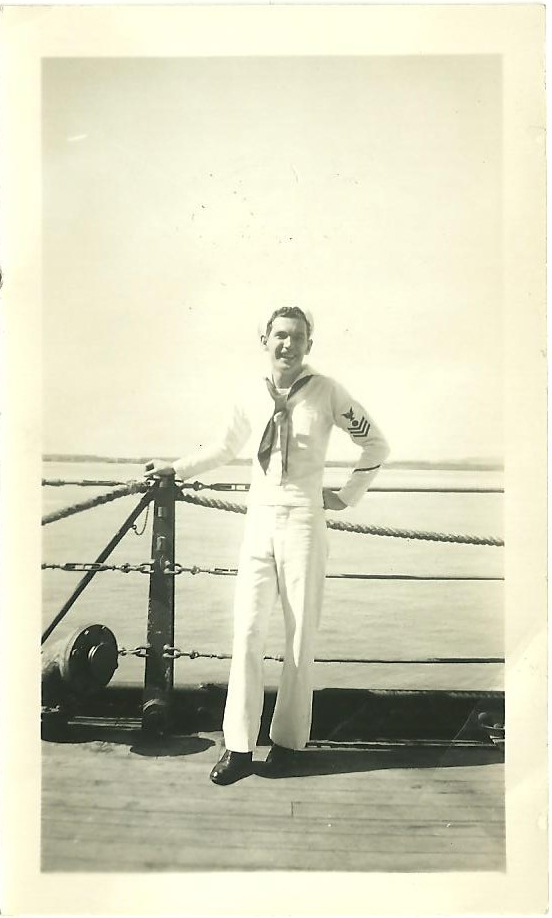

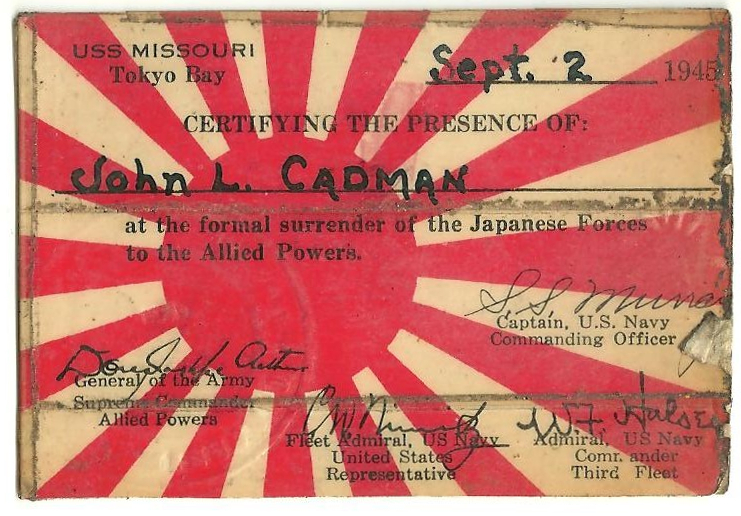

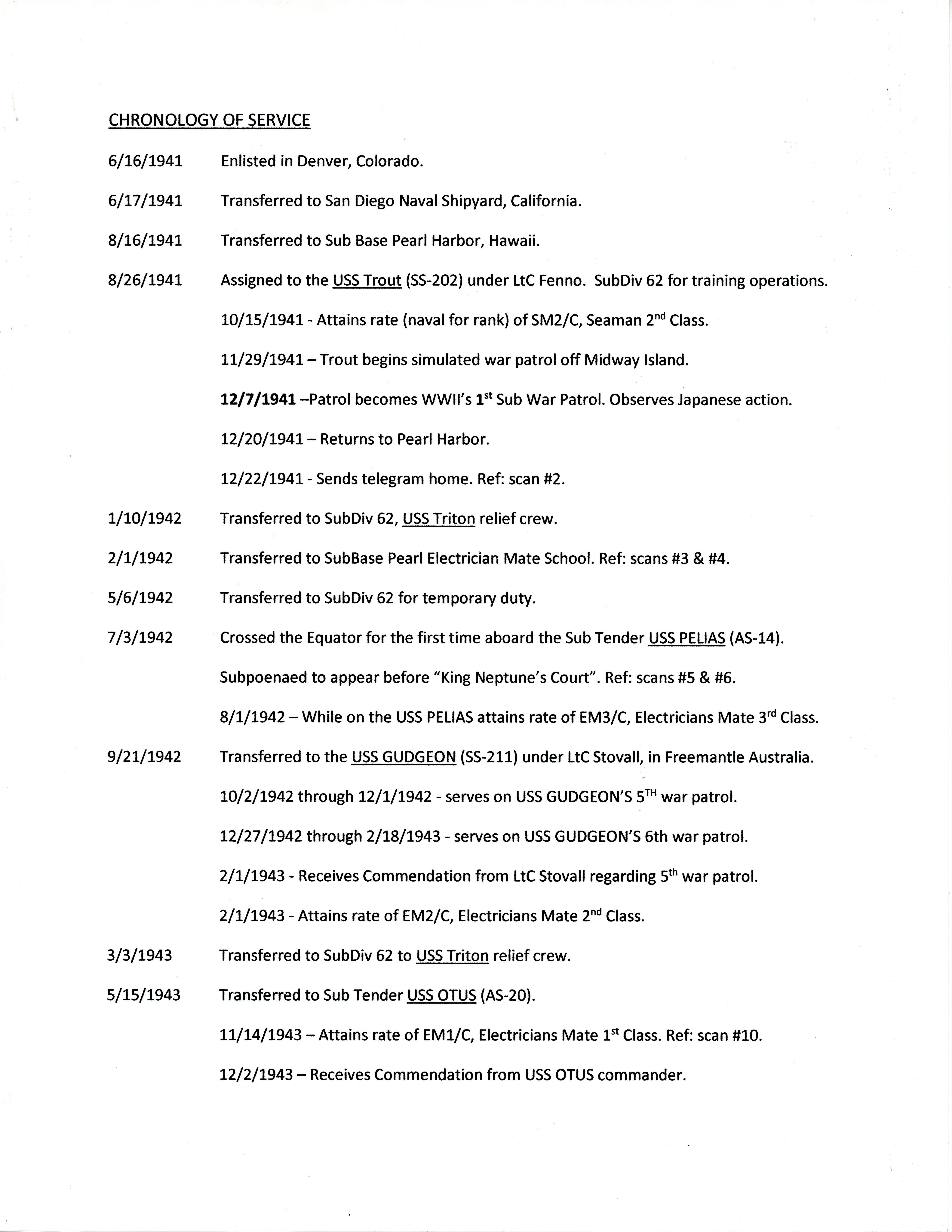

John Lester Cadman, age 21, my mother's brother and my uncle, enlisted in the US Navy on June 16, 1941. After completing basic training in San Diego, California he served in the Navy Submarine Service and the surface Navy throughout World War II. On September 9, 1945, John was present on the USS Missouri for the formal signing of the Japanese unconditional surrender.

The following narrative of John Cadman's World War II (WW II) service is based on a number of sources including sources outside of the family covering general information about the Navy's WW II activities (see Sources of Information and List of Figures below). Information specific to John's experiences was provided by two family members: 1) John's sister and my mother, Mona Cadman Moore who, serving as the family's de facto genealogist, collected, saved, and compiled photos and documents pertaining to experiences of family members during WW II, and 2) John's son and my cousin Dennis Cadman who also saved and compiled much information about his Dad's participation in WW II.

The album that my mom spent so much time and effort (particularly in the last years of her life) creating for her brother John is provided below.

Some years ago, Dennis and his wife Trudy took a trip to Hawaii to visit Pearl Harbor and donate some of John's memorabilia to the US Navy's archives. His description of that trip and the donated photos and documents are also provided below. Of particular value to me in writing this narrative is John Cadman's "Chronology of Service" that Dennis compiled as part of the donation.

US Navy Submarine Service

After basic training, John was assigned to serve in the Navy's Submarine Service. I don't know how John was selected for the submarine service, but I suspect that he was chosen from a group of newly graduated sailors who had expressed a desire to serve on submarines. I know from my experience in the Navy that, while you are in basic training, you are given the opportunity to select several desired duty stations. Which duty you are finally assigned to depends on the needs of the Navy at that time as well as on your performance during basic training and the results you achieved on aptitude tests.

During his time in the submarine service, John participated in war patrols aboard the USS Trout (SS-202) and the USS Gudgeon (SS-211).

Mike Ostlund wrote an outstanding book on the history of the submarine USS Gudgeon in World War II (John Cadman served on the Gudgeon during its 5th and 6th war patrols). Ostlund focused on the Gudgeon because his Uncle, LTJG William C. Ostlund was serving onboard the Gudgeon when it was lost at sea during its 12th war patrol. The book is entitled, 'Find 'Em, Chase 'Em, Sink 'Em: The Mysterious Loss of the WWII Submarine USS Gudgeon'. In the preface to the book, Mike writes the following with regard to the men, enlisted and officers, who were members of Navy's submarine service:

The video in Figure 2 (1 hour/25 minutes long but well worth it) does an excellent job documenting the WW II participation of the Navy's submarine service. It includes some great interviews with US Navy submariner veterans. During that period, the Navy's submarine force came be known as the "Silent Service", an appropriate appellation with regard to the Navy Department's efforts to keep news of submarine activity under specific restrictions - confining news to only a brief description of damages done to the enemy. In addition to keeping the enemy in the dark about US submarine operations, the Navy's silence served another purpose as described in this quote from the Naval History and Heritage Command website:

It should be noted that, early on, the Japanese navy's low regard for US submarine capabilities (reinforced in part by the poor performance of the US's Mark 14 torpedoes as discussed below) caused Japanese destroyers to significantly under estimate the depth capabilities of the US submarines and so set their depth charges to go off at depths above those that the US submarines had retreated to. Unfortunately, in 1943, US congressman Andrew J May made public the fact that Japanese depth charges were not set deep enough to destroy US submarines. As a result, the Japanese adjusted their depths and their anti-submarine warfare operations became more effective, to the detriment of US submarine crews.

Pearl Harbor

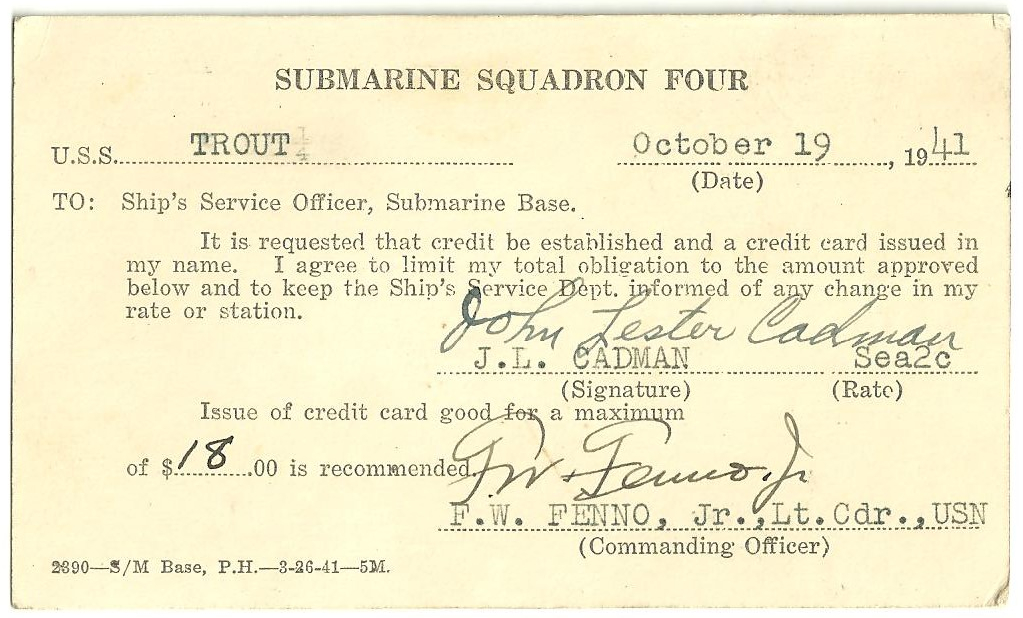

John's first duty station was the Navy Sub Base Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, where he was initially assigned to the crew of the submarine USS Trout (SS-202) (Figure 3).USS Trout

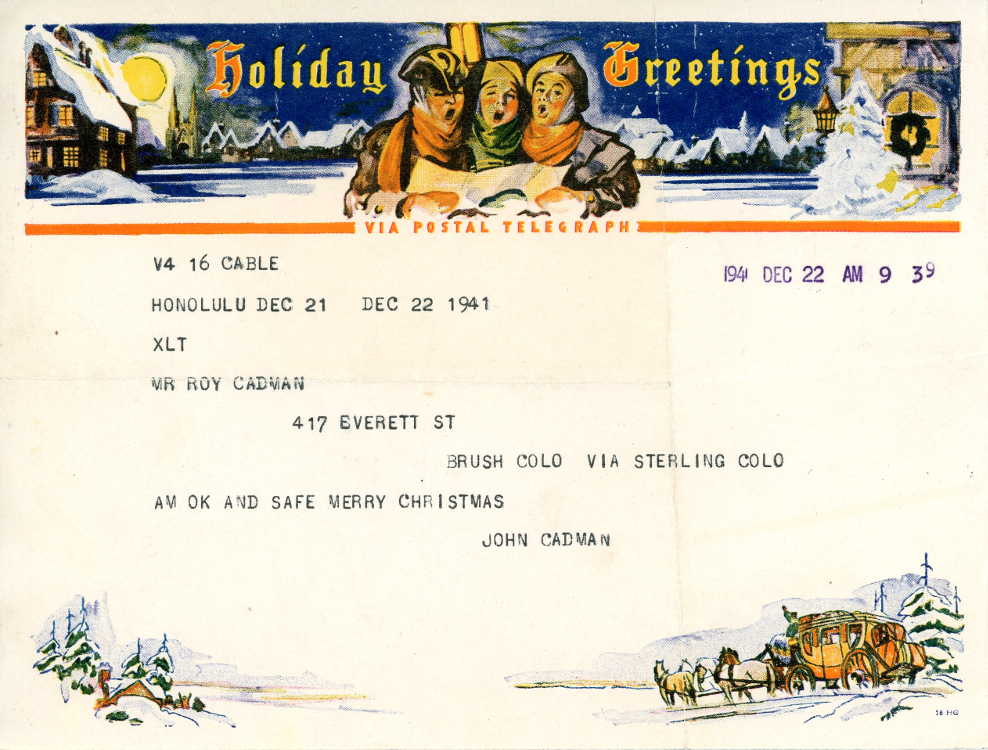

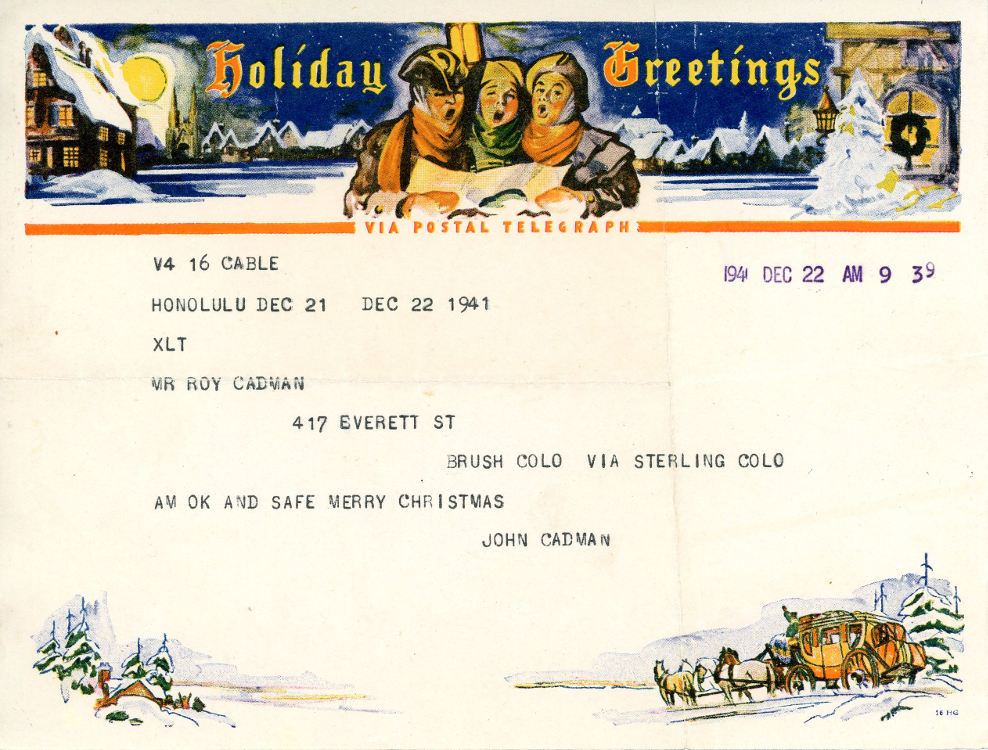

On November 29, 1941, the Trout began a simulated war patrol in waters off of Midway Island. Eight days later, on December 7, 1941, the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor and the Trout's training patrol immediately became the Navy's first WW II submarine war patrol. That night, the Trout observed two Japanese destroyers shelling Midway. After attempting to pursue them, the destroyers retired before the Trout was able to get into firing position. The submarine continued on war patrol until returning to Pearl Harbor on December 20. On December 22 John was able to send off a telegram (Figure 4) to his parents informing them that he was "OK AND SAFE".

When the Trout arrived back to Pearl Harbor on December 20, the visual picture of the wreckage and the ongoing salvage operations must have been devastating for the crew.

One positive circumstance, however, likely stood out to all of the submariners stationed at Pearl Harbor: the Japanese attackers had concentrated all of their efforts on the US Navy's surface assets; the submarine fleet, with a number of subs docked in the harbor at the time of the attack, was completely untouched by the Japanese torpedo planes and dive bombers, as were the navy's repair yards and oil tank farms. This circumstance came about because the main objectives of the attack were: 1) to send a propaganda message and reduce the will of the American people to go to war by destroying their most impressive naval assets, their battleships and especially their aircraft carriers (which fortunately were deployed away from Pearl on December 7th), and 2) to cripple the US Navy's capabilities long enough to conquer needed sources of oil such as the Dutch East Indies and develop an effective defensive posture without American opposition. Given these objectives, the Japanese planners assumed that they could accomplish them without having to expend valuable ammunition on the US subs (Figure 6, 1:35-2:21).

The Japanese planners' decision to forgo an attack on the submarine docks and fuel facilities during the attack on Pearl Harbor proved to be a serious mistake. Within six hours after the Pearl Harbor attack, the US Navy Chief of Staff ordered US Naval commanders to "execute unrestricted air and submarine warfare against Japan". This empowered naval forces to disregard existing pre-war doctrine and execute attacks against any vessels flying the Japanese flag, including commercial and civilian passenger ships. Because the US submarines at sea and in the harbor were undamaged after the attack, and plenty of fuel was available, they were able to immediately respond to the order.

As mentioned above, John's submarine, the Trout, as well any other subs performing surveillance or training missions at the time of the attack, were immediately put on a war footing. On December 11th, the USS Gudgeon, a submarine that John would later be re-assigned to, was deployed on its first offensive patrol. During the 50 days of that deployment, the Gudgeon became the first American submarine to patrol along the Japanese coast, and on January 27, 1942 she became the first US Navy submarine to sink an enemy warship in World War II (Japanese submarine I-73).

Initially after Pearl Harbor, the US Navy's submarine force was ill-prepared for war. A significant proportion of the force was older and essentially obsolete with regard to opposing Japan. Tactics were too reliant on sonar, and skippers had a undue respect for Japanese anti-submarine capabilities and so were not aggressive enough in their attacks. The fleet was spread out with individual units focused on surveillance of Japanese bases and command was too divided. But the biggest problems were the defects in their primary weapon, the Mark 14 torpedo. From Wikipedia:Mark 14 torpedo:

- It tended to run about 10 feet (3.0 m) deeper than set.

- The magnetic exploder often caused premature firing.

- The contact exploder often failed to fire the warhead.

- It tended to run "circular", failing to straighten its run once set on its prescribed gyro-angle setting, and instead, to run in a large circle, thus returning to strike the firing ship.

Torpedo failures often frustrated commanders and crew members. In the early going, subs would fire multiple torpedoes (4, 8, or more) with no apparent hits. Sometimes torpedoes were observed detonating before they got half way to the target. Other times torpedoes could be heard hitting the target but no detonation would occur. Although the Mark 14's problems were not resolved until September, 1943, the Navy's submarines did have some early success in sinking Japanese vessels and the submarine fleet performed many other tasks which contributed greatly to the war effort. These included reconnaissance patrols, landing special forces, search and rescue missions, and special operations. One of the spec ops involved the USS Trout, the submarine John was initially assigned to. It took place in January, 1942 shortly after John had left the Trout for a new assignment and is dramatized in the following video from "The Silent Service", an American syndicated television series of the 1950's:

On January 10, 1942, John Cadman was temporarily re-assigned to the USS Triton relief crew. This was the first of two instances that John was assigned to relief crews. The following quote from the Naval History and Heritage Command website explains the purpose of the relief crews:

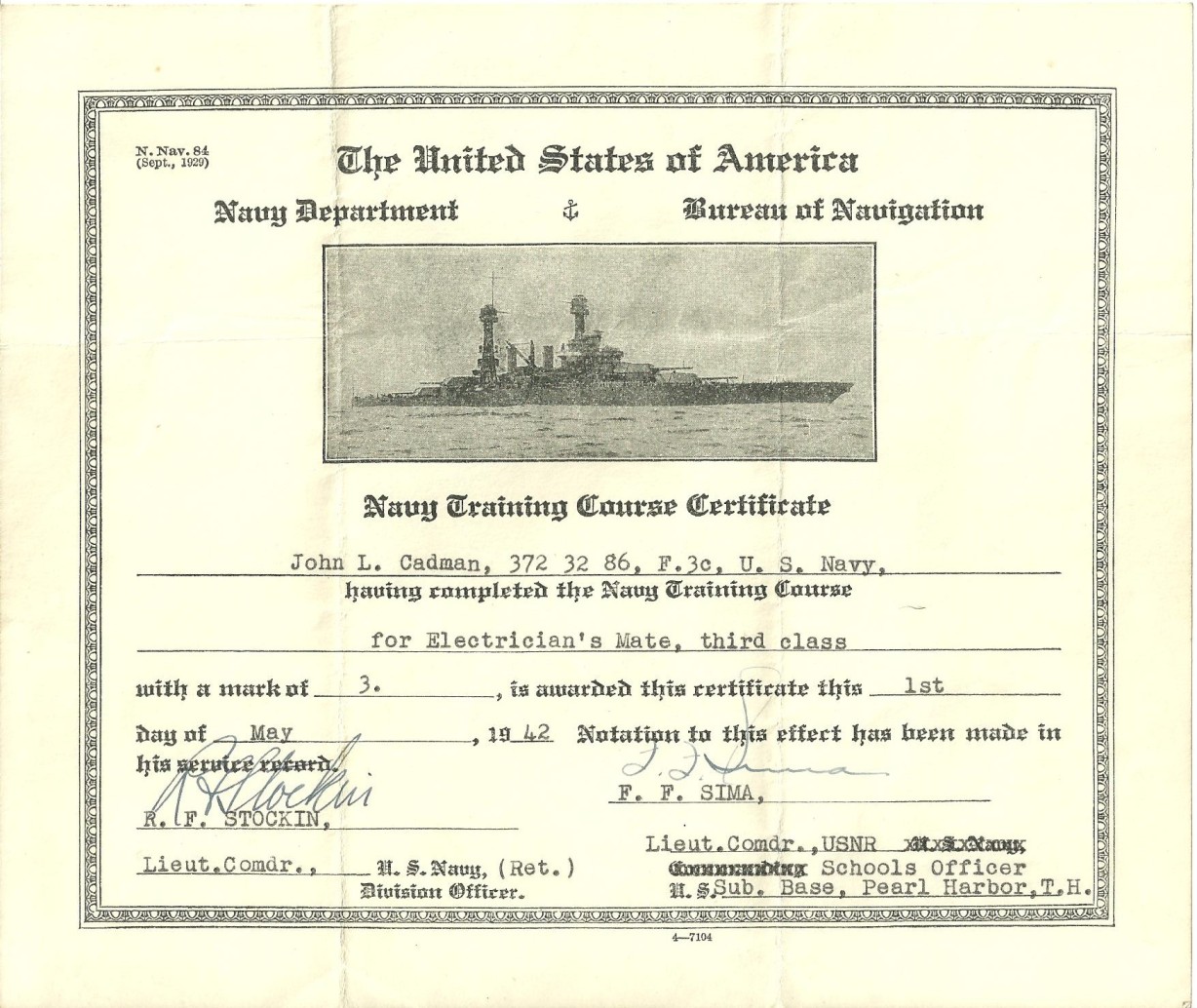

While on relief crew duty, John was selected for Electrician's Mate School and started classes on February 1, 1942.

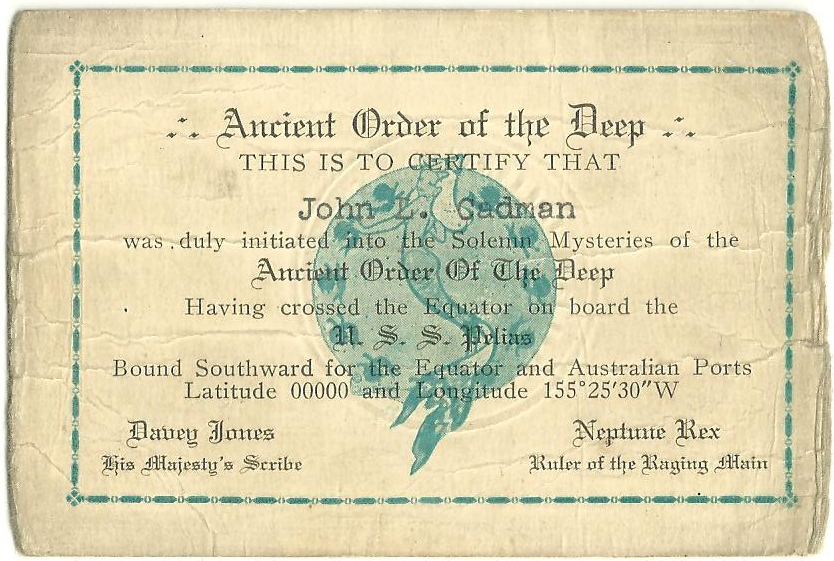

On To Freemantle

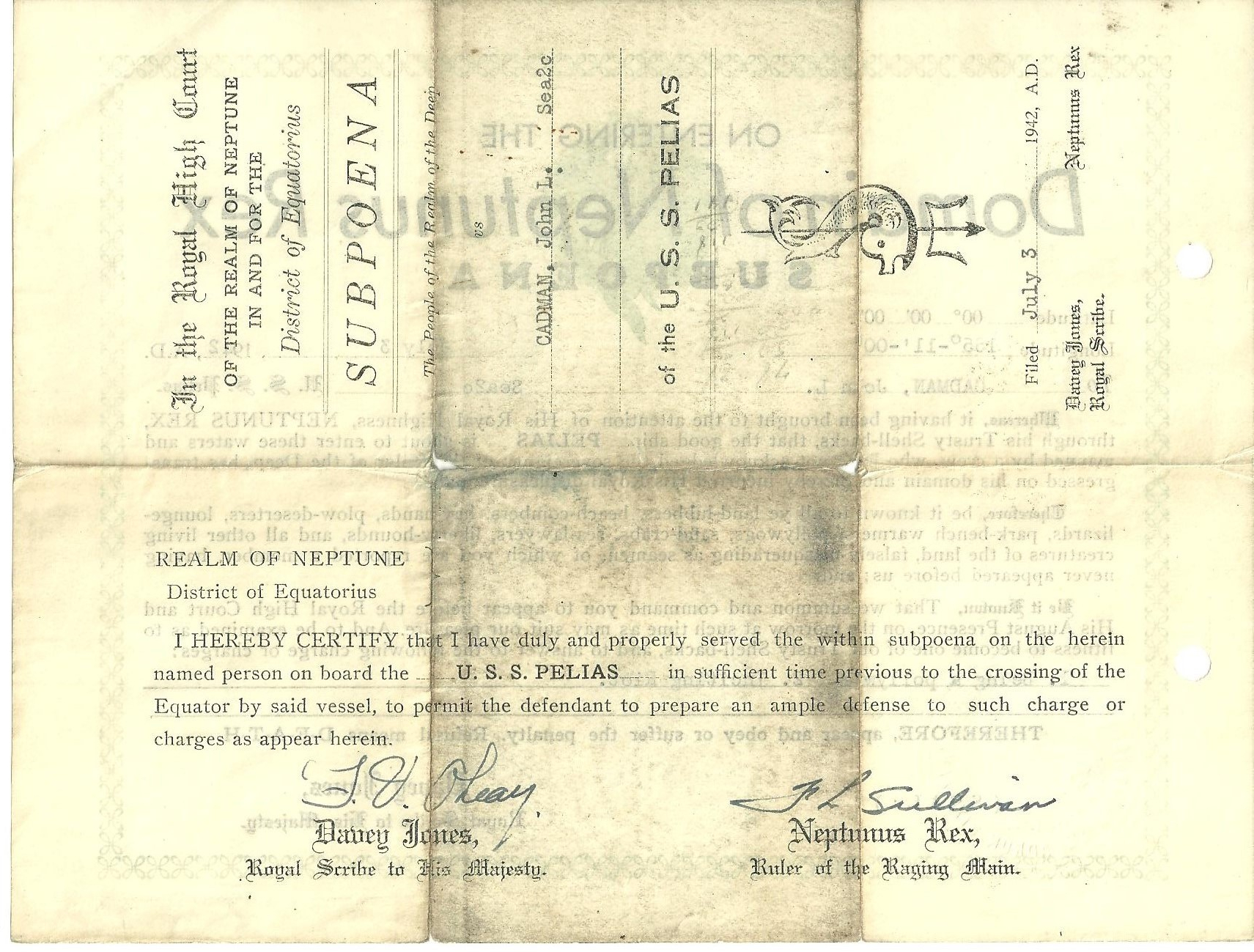

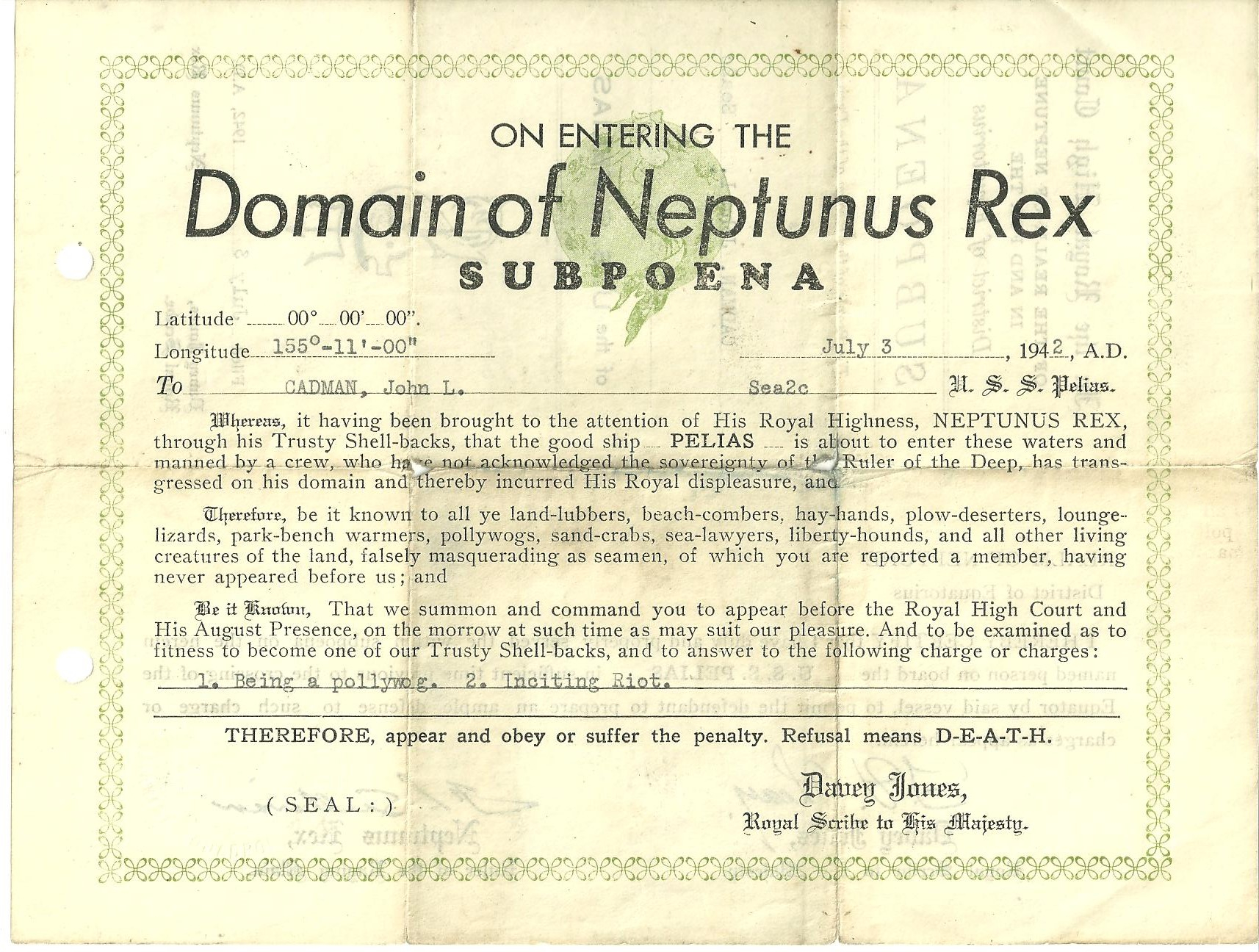

After completing EM school, John was transferred to SubDiv 62 and subsequently embarked aboard the sub tender USS Pelias (AS-14) headed to the US submarine base that had been established in Freemantle, Australia. On July 3, 1942 he crossed the equator for the first time and while in transit, he attained the rate of Electrician's Mate 3st Class (EM3).

On September 9, 1942, after arriving in Freemantle, EM3 John Cadman was transferred to the USS Gudgeon (SS-211) under the command of LCDR William Shirley Stovall.

USS Gudgeon

Note: The following narratives of the Gudgeon's 5th & 6th war patrols are largely paraphrased from Mike Ostlund's 'Find 'Em, Chase 'Em, Sink 'Em: The Mysterious Loss of the WWII Submarine USS Gudgeon'.

USS Gudgeon - 5th War Patrol

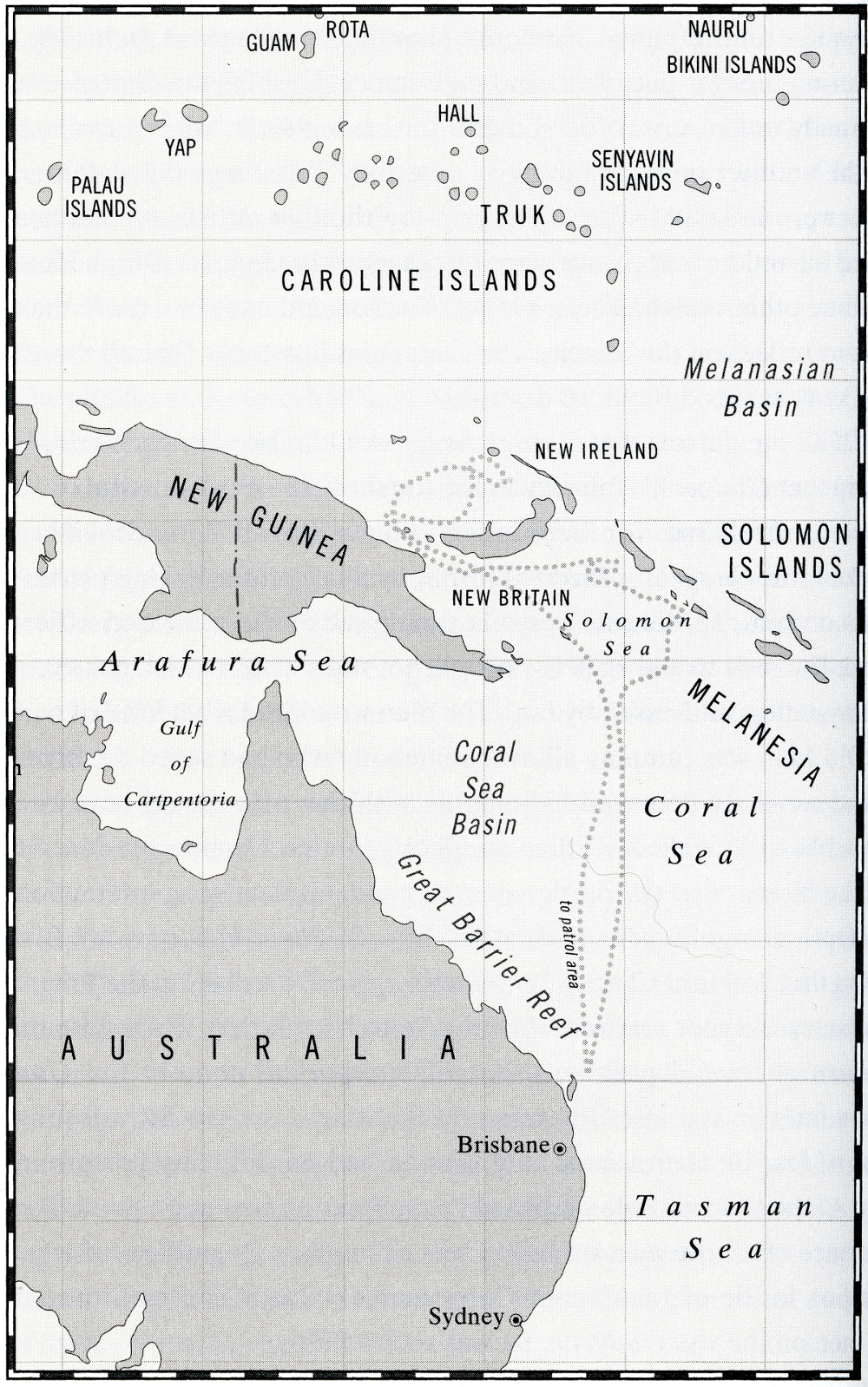

On October 8, 1942, the USS Gudgeon completed a transit from Freemantle and arrived at Brisbane on the eastern shore of Australia. Later that same day, the Gudgeon pulled away from the sub tender USS Griffin and embarked on her 5th war patrol with LCDR Stovall and sixty-seven other men aboard, including EM3 John L Cadman.

First Engagement

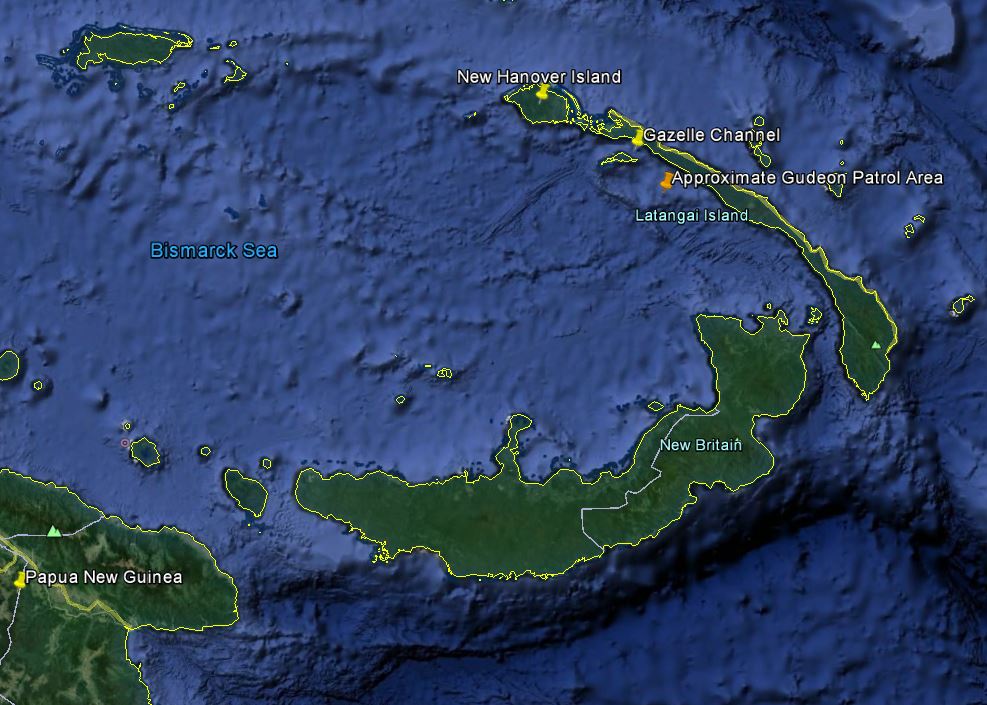

On October 17, the Gudgeon arrived south of New Hanover Island, part of the Bismarck Archipelago, slightly northeast of New Guinea and was positioned to intercept shipping proceeding south from the Gazelle Channel (Figure 14).

At this point I am temporarily abandoning my effort to paraphrase Mike Ostlund's narrative and instead provide some of the real thing (there are numerous dramatic descriptions such as this one throughout Mike's book - if you have read this far, you probably should go ahead and buy the book):

"Cat-and-mouse games with Japanese ships of war continued until October 21 at 0850 when Gudgeon, still off New Hanover Island, sighted a convoy of five large merchant ships escorted by two destroyers. The convoy was fifteen miles away and smoking enough to attract the hungry Gudgeon. Stovall had Gudgeon in what appeared to be a near-perfect position at about a right angle to the target vessel at periscope depth. The only thing that could make things better was for the destroyers to head in the other direction, turning Gudgeon loose on the convoy like a shark at a crowded beach.

The lead destroyer, always on the lookout for American submarines, continued to guide the convoy from the left-hand side of the cluster of ships, with the second destroyer in position behind the convoy on the right-hand side and quite distant from Gudgeon. Because the sea was like a mirror, Gudgeon’s periscope could be easily seen. Stovall and Dornin decided to fire at the two ships nearest Gudgeon, from the starboard side of the target vessels. This plan would allow Gudgeon the greatest chance of escape.

The ships in this convoy were old and seemed to be badly in need of upkeep, which might have explained their very slow speed. According to the Japanese Merchant Ship Recognition Manual, the target ships appeared to be about seven thousand tons and were similar to the Takatoyu Maru. Each ship was about 450 feet long and decrepit enough that Stovall was certain that one hit would be enough to sink them.

At 1112 the attack began. With the men in the forward torpedo room rubbing the Buddha and about ten-second intervals between fish, Lieutenant Commander Stovall roared, “FIRE ONE. FIRE TWO. FIRE THREE. FIRE FOUR. FIRE FIVE. FIRE SIX.” All six torpedoes, three aimed at each ship, were now in the water seeking their prey. The first target was thirteen hundred yards away. Each torpedo was set to run at a slightly different angle, making it more likely that a hit would be obtained. For the second target, farther away, a less-divergent angle was desired, as the target was actually around 3,500 yards—two miles from the submarine. The torpedoes were set to run at fourteen feet so that they would actually run around twenty-five feet.

Stovall observed that the ships seemed to be running high in the water, as if they were not very heavily loaded. Timed hits were heard at 1113, 1114, and 1117, which suggested that the torpedoes blew up about when they were supposed to, and that two hits were made on the first ship, one on the second. Stovall noted that the third torpedo did not explode for a long time, possibly because the range to the target was underestimated by a thousand yards—or more likely, because the second target was turning away when it was hit, thus increasing the distance between submarine and target ship.

The first hit was observed through the periscope and appeared to be amidships. Stovall saw a great deal of smoke and very little water geyser, causing him to feel confident of a desirable bottom explosion. By the time the second explosion was heard, Stovall was eyeing the two escorts, now angrily searching for Gudgeon. When the third torpedo exploded, Gudgeon was going deep and rigging for depth charges.

Just three minutes after the last torpedo hit its mark, with both destroyers steaming full speed toward Gudgeon, the expected depth charge attack started. Curiously, Stovall noticed that the depth charges were being thrown only one or two at a time rather than in massive barrages, like the ones in the bone-jarring, sixty-depth-charge attack of the fourth patrol. Stovall counted fifty-one explosions altogether, some of which sounded like ships breaking up as they went down. Only about eight had the characteristic sound of good close depth charges.

After each attack ended, the destroyers would stop, listen, and use their sonar. While the attack was going on, Skipper Stovall had cleverly maneuvered Gudgeon close to and behind the second target ship, then between the two merchant ships toward the tail end of the convoy, using the noise of the enemy ships’ screws and their wakes to confound the Japanese counterattack. The clever maneuvers under extreme duress worked. Gudgeon sustained no damage.

Ray Foster remembered this escape very well. He said that Gudgeon “ducked in underneath the first ship. The boilers were blowing out, and we could hear debris hitting on our deck, and the destroyers were going around in circles dropping depth charges, killing everybody that was in the water.” When Foster described the disintegration of the Japanese vessels and, in particular, the boilers blowing up, he is in effect stating that at least one of the ships went to the bottom.

After two and a half hours of skillful maneuvering, Gudgeon rose to periscope depth and saw that one of the destroyers was still in the area of the attack, possibly still searching for the underwater hunter, or for survivors. The destroyer was not close to Gudgeon’s actual location. Many of the Japanese merchant marines endured an awful death. One minute they were boldly traveling through the waters off the Bismarck Archipelago, prideful and superior in their position of service to the emperor, and then suddenly their ship was blown out from beneath them. Those thrown from the ship and still alive instinctively struggled for survival. They reached for lifeboats or wreckage or anything to cling to, floating helplessly as they watched their own destroyers plowing through the waters straight at and around them at full speed. The screams and moans of dying men slowly lessened as they rode the white crests of the waves and then let go, their bodies floating lifeless in the water.

It was not catastrophe for all those thrown into the sea. Dusty Dornin recalled that some of the men made it to safety. “We saw considerable wreckage and life boats and one transport listing heavily to port and the survivors being taken off by the destroyer.” A short while later a seaplane joined the search for Gudgeon. William Stovall decided that it would be wise to move on rather than remain and allow the seaplane time and opportunity to coordinate a fatal attack on his submarine. At 1946 Gudgeon surfaced far from the chaos she had created. By 2209 recovery from the attack was interrupted by another patrol vessel, which smelled blood and was quickly closing on Gudgeon. Stovall ordered the crew to dive to 270 feet and rig for another depth charge attack. At this time in the war, the commonly held belief was that if the submarine went two hundred to three hundred feet down, she would be safe because the Japanese tended to set their depth charges to explode at a much shallower depth. This time, a depth charge attack did not occur because of Stovall’s evasive maneuvers. The maneuvering must have been particularly skillful, because at one time the little ship was actually rather close astern. Gudgeon would be given wartime credit for having sunk an unknown seven-thousand-ton cargo ship and postwar credit for having sunk the 6,783-ton Choko Maru."

Second Engagement

Gudgeon's next significant encounter with the enemy occurred in the vicinity of New Hanover Island on the night of November 11, 1942 when a trail of smoke was observed on the far horizon. After LCDR Stovall changed course and headed for the smoke, they spotted a convoy of five merchant-type ships of about 7,500 tons, escorted by two destroyers. Remaining on the surface, Gudgeon first lined up for a straight bow shot on the second ship in the convoy and fired three torpedoes from the bow tubes. One explosion was heard and the men in the sound room reported that one of the two screws that they were hearing close together had gone silent.

Before the hit could be observed, the Gudgeon quickly swung left and lined up for a shot on a second merchant ship. Three more torpedoes were fired from the bow tubes and three timed explosions were heard. Gudgeon again swung left to line up for her final shots. At that point LCDR Stovall, on the Gudgeon's bridge, observed two hits on cargo ship four.

The Gudgeon was then positioned so that the three stern tubes were brought to bear on cargo vessel five. Three more torpedoes were fired and resulted in two hits with one seeming to blow the vessel apart. The powerful concussion was felt "severely" on the bridge and the underwater shock experienced below decks on the Gudgeon was "a great deal more severe than that experienced from other hits". The officers speculated that the ship must have been carrying ammunition although there was some confusion as to which ship was hit or whether one of the destroyers was the victim. There was not time to stop and evaluate as the first destroyer was now observed steaming toward them. Using all four engines, the Gudgeon was able to put distance between the escorts and escape. At that point, LCDR Stovall ordered that the torpedo tubes be reloaded but a follow-up attack was stifled by a sudden tropical rain storm. While retreating from the area, occasional explosions were heard far behind the submarine. These were interpreted as coming from the stricken ships. Gudgeon received wartime credit for having sunk two 7,500 ton merchant ships and damaging a third.

Third Engagement

The final significant encounter with the enemy during the Gudgeon's 5th war patrol occurred about midnight on November 24, 1942. Another small cluster of enemy ships comprised of two merchant vessels and three destroyer escorts, three ahead and one astern, was sighted. Disregarding the challenge of taking on three destroyers, LCDR Stovall began maneuvering the Gudgeon to attack.

Again, from Mike Ostlund's book:

At 2037, with the bright moon putting the surfaced submarine in even greater peril, he ordered that Gudgeon pull in from the starboard bow, remaining very low in the water with the deck awash in order to stay out of the moon track. Gudgeon closed to about six thousand yards and was preparing to dive when a flash from the right-hand lead destroyer was seen. With a three-gun salvo ringing in the distant night, Gudgeon dove deep and rigged for depth charges. The shots all missed, having been fired long. So long, in fact, that the men on the deck did not have any real idea where they had hit. With the klaxon sounding “dive” and the men hurrying about, the destroyers fired no more shells from the deck guns. As the submarine passed ninety feet, a loud swishing noise was heard moving past the hull. The object had not been accompanied by the characteristic crack of a shell hitting the water. It was a torpedo passing dangerously close to the submarine.

Having avoided being sunk by the torpedo, the men on sound could now clearly tell that the three Japanese destroyers were bearing down on them at high speed. Gudgeon started evasive tactics utilizing radical course changes. The boat was once again in mortal jeopardy. Three destroyers. One submarine. Frightening odds indeed. The Japanese knew about where Gudgeon was, a fact that had been made obvious by the torpedo—sounding very much like a truck—missing Gudgeon by the narrowest of margins. Only clever defensive maneuvers would save her, and lots of luck.

The destroyers would periodically make way at full speed and then stop abruptly, hoping to catch Gudgeon in movement so they could line up a fatal depth charging. At 2053 the attack continued. The air conditioners were turned off. The heat was stifling. The men on board were silent, sweat streaming down their bodies onto the submarine’s deck, their hearts pounding. Flight was impossible. The men were stuck in a 307-foot submarine with three enemy destroyers above them dropping depth charges. The patrol report indicates that thirteen charges were dropped at various intervals. The spacing was not regular because two destroyers were dropping their charges at the same time. To the men on the submarine, the lack of an expected rhythm made the attack even more unnerving.

Dusty Dornin [LT Dusty Dornin, the sub's torpedo officer] would say later, “Upon reaching 180 feet, a barrage of approximately nine depth charges was dropped fairly close, within one hundred yards.” BOOM. BOOM. BOOM. BOOM. BOOM. BOOM. BOOM. BOOM. BOOM. “These three destroyers proceeded to work us over for one hour. Two departed and one remained in the area to keep us down and prevent us from making a further attack on this convoy. We were able to surface approximately four hours after these antisubmarine measures, but we were never able to close the convoy again.”

At 2212 Gudgeon sustained another four-depth-charge barrage. BOOM. BOOM. BOOM. BOOM. With the destroyers heading east and Gudgeon making way southwest, the attack was soon over, with neither the Japanese nor Gudgeon being much worse from the encounter. Gudgeon surfaced at around 0120 the next day about twelve miles from the place of the attack. No ships were in sight. One thing seems certain: If the torpedo had been fired a little more accurately, Gudgeon’s war would have ended right there and then.

When asked later in the war whether he ever got accustomed to a depth charge attack such as the one he had just suffered through, Dusty Dornin replied, “Well, I’ve read in our prewar dope, it said that due to experience and training and discipline that you get accustomed to it. Personally, I don’t think I will ever get accustomed to it. I don’t like them; they scare me. I think they scare everybody. But after all, you just go ahead with your business; it just makes your heart pound a little more, that’s all. I don’t think I will ever get accustomed to depth charges.”

Return To Brisbane

After 49 days at sea, the Gudgeon ended her 5th war patrol and arrived at her port at Brisbane on December 1, 1942. She had successfully engaged two enemy convoys and eluded an aggressive attack from the destroyer escorts of a third without suffering significant damage. Although, owing to insufficient evidence, the Joint Army Navy Assessment Committee (JANAC) would eventually only acknowledge that the Gudgeon had sunk one enemy vessel (6,733 ton Choko Maru), Admiral Christie, commander of Task Force Twenty-Two, endorsed the efforts of the Gudgeon and wrote that it was "beyond doubt" that three enemy merchant vessels were sunk and one damaged; with the possibility that an enemy destroyer was also damaged. Christie also praised the excellent efforts of the entire Gudgeon crew.

Admiral William F "Bull" Halsey, Commander South Pacific Area, was initially mildly critical of LCDR Stovall's fuel expenditures in the first six days of the patrol, and for having been detected in the course of several attacks, but later issued a statement commending the Gugeon's efforts: “The patrol in general was thoroughly satisfactory and the performance of the ship, its officers, and crew commendable throughout. The skill displayed in accomplishing the multiple-target attacks was outstanding. It is noted that Lieutenant Dornin is given credit for largely contributing to the successes attained.”

As for young John Cadman, no doubt he had his eyes opened wide regarding the nature of intense submarine warfare and gained valuable knowledge and experience that would serve him well in the upcoming 6th war patrol of the USS Gudgeon.

USS Gudgeon - 6th War Patrol

After 3 weeks of R&R for the crew and repair and overhaul for the submarine, the Gudgeon pulled away from Brisbane on December 22, 1942, destined for her 6th War Patrol. Her initial departure was soon curtailed 150 miles out after the subs' first dive revealed leaks that not been repaired, followed by the crankcase for the number two engine blowing up. The damage caused LCDR Stovall to turn the Gudgeon around and head back to Brisbane, arriving on the 24th.

Villamor Landing

On the 25th, while still undergoing repairs, the Gudgeon was given a new assignment to carry out on her 6th war patrol. About 2,000 pounds of special gear were loaded onboard to support a special operation to be carried out by Major Jesus S Villamor. Villamor was a Filipino pilot who had proved his courage countering Japanese aircraft over Manila following Pearl Harbor. After being awarded the Distinguished Service Cross by General Douglas MacArthur, Villamor requested, and was granted permission by MacArthur, to lead to lead a group of commandos in an operation to his homeland to coordinate anti-Japanese guerrilla activities and establish an intelligence network in the Phillipines.

Villamor and five accompanying commandos, disguised as submarine mess boys for security purposes, boarded the Gudgeon and were bunked in the forward torpedo room. The group came be known as the "Planet Party" because of Villamor's decision to use planet names as code words for the various Philippine islands. They were described by one crew member as an impressive group of "fierce looking" fighters but blended in well with the submariners. On December 27, 1942, the Gudgeon departed Brisbane for the sub's 6th war patrol.

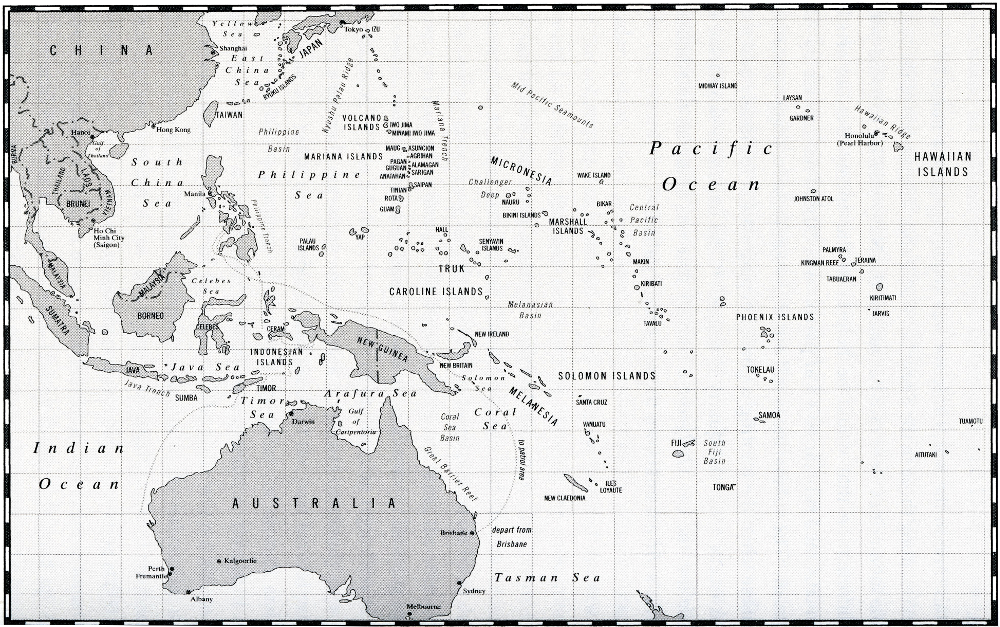

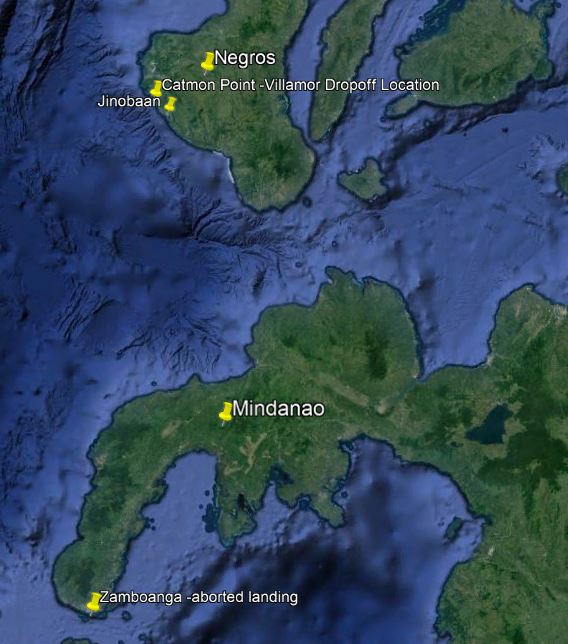

The transit to the drop off location for the Planet Party required navigating through the hundreds of islands between the Solomons and New Guinea, past the Admiralty Islands, and northwest toward the Philippines (Figure 15). Although LCDR Stovall was on the hunt for targets along the way, the passage was relatively uneventful. On December 31, Gudgeon executed a precautionary dive upon getting a report that a Japanese sub was in the area but no further action was initiated. Navigation during the trip was difficult because of overcast weather. The first fix obtained indicated that the Gudgeon was fourteen miles off course. The weather cleared by the time they reached Mindanao and on January 11th, they closed on a Japanese submarine running on the surface but the target dove or was lost over the horizon. At that point they began searching for a landing place for Villamor and his men.

The plan was to land Villamor on the southern island of Mindanao. As they approached Zamboanga (Figure 17), a Japanese-occupied location on the tip of southwest Mindanao, they passed numerous small fishing boats. At 1859 on January 12, 1943, the Gudgeon surfaced to identify a drop off location. On the evening of the 13th, as she began to approach the selected location, numerous fishermen with lit torches were observed on the beach and the landing was canceled.

In the book he later wrote, "They Never Surrendered: A True Story of Resistance in World War II", Villamor described his thoughts as he looked upon his Japanese-occupied homeland that evening:

The Gudgeon proceeded north toward the island of Negros, code-named Neptune by Villamor. The next evening, recognizing the Planet Party's disappointment in having to cancel the drop off, Gudgeon cooks prepared a special meal jokingly referred to by one of the crew as the "The Last Supper" in anticipation of a successful landing the next day.

From Mike Ostlund:

On January 14, 1943, LCDR Stovall had his boat on the surface and cruising up and down the coast of Negros looking for a good landing spot. An uninhabited sand beach was identified at Catmon Point (Figure 17) that was also near to the little village of Jinobaan, which presented an opportunity for Villamor to make immediate contact with the natives.

Stovall called for the Planet Party to join him on deck. They agreed to start loading the rubber rafts and execute the landing. Loaded on the rafts were arms, ammo, clothing, batteries, generators, spare parts, gasoline, dynamite blasting caps, two small radio sets, canned rations, gems worth 4,000 pesos, and 350,000 pesos from the Bank of Australia. Villamor crawled into the lead raft with two of his party and a Thompson submachine gun.

As the rafts separated, Villamor told helping crew members that he would entertain them at the Manila Hotel once the war was over. At 1927, the landing party disembarked from the rafts and began dragging them to the shore as the Gudgeon's guns were brought to bear on the beach in case the Japanese showed up. Once the party was safely on the beach, the Gudgeon retreated to a position further off shore.

Shortly after landing, Philippine guerrillas, unaware of the commando operation, captured one of two Planet Party groups that had formed. The other group, comprised of Villamor and two companions, were able to hide in the woods. At that point, realizing that the Gudgeon was still in a vulnerable position on the the surface off shore, Villamore used his lamp to flash a prearranged signal and the Gudgeon moved further out to sea and dove. The following morning Villamor's group was also captured. Initially, the guerrillas were convinced that the Planet Party were Japanese collaborators. While their prisoners were being held at gun point, an old man appeared from the dense undergrowth and walked toward them. After inspecting the prisoners, the old man, who turned out to be the guerrilla leader, Captain Jorge Madamba, huddled with the guerrillas and explained to them that they had captured Major Jesus A Villamor, already known even in this remote location, as a hero to his people for his exploits as a pilot.

Jesus Villamor with his commando companions, went on to complete one dangerous wartime mission after another. As a commando intelligence officer, Villamor's reports from the field were later publicly lauded by President Eisenhower, he was awarded the Philippine Medal of Valor, and the Philippine Air Force's principal facility in Manila was renamed Colonel Jesus Villamor Air Base.

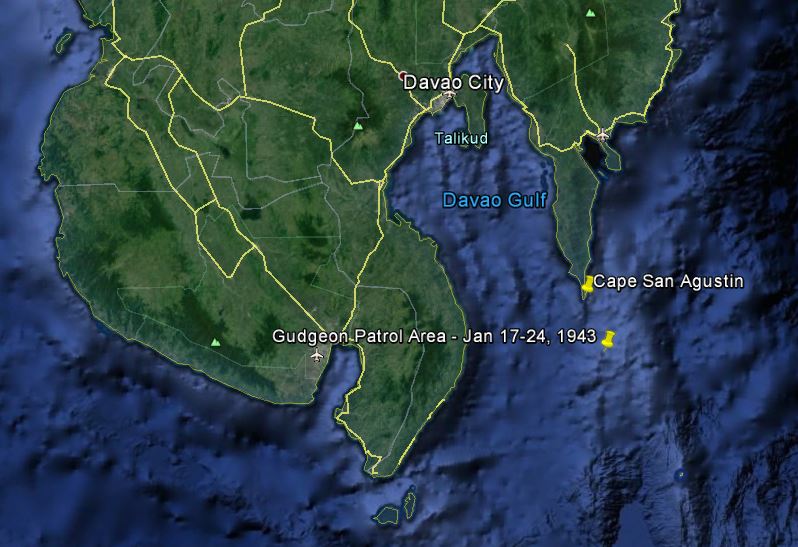

After completing the drop off of Villamor and the Planet Party, the Gudgeon headed toward it's next patrol area. On January 17th, she arrived at Cape San Augustin, adjacent to the Davao Gulf (Figure 18) in what LCDR Stovall hoped would be a busy merchant traffic lane off the southeastern coast of Mindanao.

Concurrently, with the Gudgeon's arrival at Cape San Augustin, a small group of Allied commandos operating on the Japanese-occupied island of Timor and lead in separate groups by English Captain Douglas Broadhurst and Australian Lieutenant Frank Holland, received word that the Japanese were closing in on them. Thus began a race for their lives west across Timor that would ultimately end in a desperate extraction from the island involving the Gudgeon a month later. Their story would later be told in a book about Holland's life called "El Tigre".

Ambush At Ambon

The Cape San Augustin patrol did not prove fruitful for the Gudgeon. Only one small boat was sited and when the sub maneuvered ahead of the boat in hopes of encountering an accompanying merchant ship, none was found and the small vessel was lost due to poor visibility. On about the 23rd of January, LCDR Stovall ordered the Gudgeon out of the Cape San Agustin area and headed southeast toward Ambon Island in the Indonesian provice of Maluku (Figure 19).

On the 25th, in route to Ambon, the Gudgeon had to dive to avoid being bombed by a Japanese patrol plane. Otherwise, the Gudgeon commander and crew continued to be frustrated by the lack of targets after thirty some days without firing a shot. Upon arriving at Ambon, the Gudgeon began trolling for targets at the entrance to Ambon Bay. What happened next is best described by Mike Ostlund's narrative in Find 'Em, Chase 'Em, Sink 'Em:

A scrawny patrol craft seventy-five to one hundred feet in length was sighted. Gudgeon approached slowly as the little boat employed echo ranging to search the seas for enemy submarines. At 0735 Stovall set up for a torpedo attack from the stern tubes at one thousand yards. A few minutes later, as Stovall eyed the Japanese vessel, her gun crew and lookouts in their khaki shorts were in turn scanning the seas with binoculars. Stovall decided that the little boat was too small for a torpedo attack and ordered Gudgeon to start moving away to avoid being detected.

It was then that the Japanese ship picked up Gudgeon by short-scale pinging. The Japanese fired up their engines and turned toward the submarine. As the patrol vessel turned, Stovall feared that his periscope had been seen and that the enemy knew exactly where Gudgeon was positioned. He was correct. The skipper later wrote in the war patrol report that only two feet of scope had been exposed for ten seconds. That is all it takes sometimes, especially with the sea as flat and calm as it was on that day. The small ship was now speeding toward Gudgeon; within four minutes, she threw a cluster of four depth charges close astern to the underwater vessel, causing what Stovall said was “considerable jar” but no serious damage. Stovall started evasive tactics.

Even depth charge attacks that are not particularly close can be jarring to the nerves because sound travels best in dense hosts like salt water and steel. In an ocean at fifty-nine degrees Fahrenheit, for example, sound travels four times faster than above the surface. Because of the rapid speed, the human ear cannot discern which direction the sound is coming from, since both eardrums are struck at the same time with equal intensity. When a depth charge blows up at a distance of seventeen hundred yards, the explosion is heard one second after the detonation. Because the sound is traveling so fast, it gives the illusion that the depth charge is much closer than it actually is. The experienced submariner knows that the submarine is safe when the depth charge clicks before the deafening explosion. The clicking noise signals that the charge is surely some distance off. After the charge went off a shusssh sound could be heard through the boat. This was the sound of the water moving through the superstructure created by the explosion.

They had excellent sound gear and knew how to use it. The little ship was running almost parallel to Gudgeon from back to front. The men on board were certain that their luck had run out. All the enemy had to do now was drop the depth charges at the right depth and Gudgeon would be nothing more than a forgotten name in the war records. Sure enough, the Japanese skipper dropped four more depth charges, which rocked Gudgeon like she had never been rocked before. Damage was especially severe in the after part of the boat. The charges were very close to the starboard side of the submarine and set to explode at approximately 250 to 330 feet. With Gudgeon at 315 feet, the Japanese had estimated the submarine’s depth rather accurately and nearly sent the men to the bottom.

Stovall later wrote that the latter four depth charges caused the most severe shock ever felt on Gudgeon. Damage from the tiny ship with the accurate depth charges was considerable. In the forward torpedo room the emergency freshwater tanks were split and the QC sound head shafts were binding. The forward battery compartment, the control room, the conning tower, the pump room, the after battery, the engine room, the maneuvering room, the motor room, the after torpedo room, and topside also sustained damage. Leaks sprayed water and air all over, gauges broke, oil leaked, lightbulbs shattered, and the ship started to vibrate, mainly aft. In all, sixty-two damaged units were listed in the post-action report. Most sobering of all was the dished-in hull in the after torpedo room; this damage confirmed that the charge was at about Gudgeon’s depth and close aboard, starboard of that compartment, and had all but ruptured the submarine’s hull. Miraculously, electrician’s mate John L. Cadman was the only man to have sustained a wound. He was cut on his knee by flying glass. Two other sailors sustained injuries when they were knocked out for a while after being thrown against the bulkheads. Some of the men sported bruises for some time after the attack.

George Seiler was at his usual post in the forward torpedo room at the time the side of the boat dished-in and vividly recalled the frightening encounter. He was certain that the depth charges were unusually large and said that he thought they were being towed by the Japanese patrol vessel and were cut loose when the Japanese gauged that they were above Gudgeon. These bombs really ripped the submarine. Seiler said he actually saw the pressure hull of the submarine cave in. He also had the sobering experience of having one of the manifolds come loose and fly across the torpedo room into his lap. “It happened so fast you didn’t have time to get scared,” he said of the experience.

Seaman First Class Ron Schooley of Berkley, Michigan—on board for the second of what would be five runs on Gudgeon—recalled the attack and called it the most severe one that he ever experienced on a submarine. Schooley, a man of few words, offered a succinct and vivid description of what it was like to undergo a close depth charging. He said that the experience was something that you had to be there to “appreciate” and added, “It’s like putting yourself into a [metal] garbage can and having somebody beat the god-damned thing with a club.” By this time in the war, Ray Foster, known as “Guts,” would show those around him the reason that he had acquired the nickname. His shipmates vividly recall him lying in his bunk during these attacks, eyes upward as if he were challenging the Japanese, yelling at them as if they could hear him, fist clenched as if ready to strike, “That’s right, you bastards, use up all of your god-damned ammunition.”

In the midst of this brutal attack, the men on the submarine heard rain off in the distance. The clever Shirley Stovall seized the God-given opportunity and quickly headed toward the squall. Arthur Barlow recalled the evasive maneuvers used in silent running and the eventual escape made by Gudgeon at Ambon. “It’s a combination of trying to be quiet and get out of there. So every once in a while we would get a full blast from the screws to get running. In the distance we heard a squall. When rain hits hard on the surface of the water, it sounds like drums. So we headed for the squall. If you can imagine fifty to sixty drummers like the beating of a drum. We just maneuvered and got rid of them. We got rid of them through the squall.”

Chuck Ver Valin recalled the exhilaration of reaching the surface in the rain squall. “We just got the hell out of there. We put all the main engines online and run on batteries only. We had to come up. Our air was low and everything else, and the power was practically down to nil. When we came up, we thanked the Lord it was raining like hell and the seas were up. I’m telling you when they opened that fricking hatch and that air come down there, oh what a feeling that was. Everyone was standing on the ladders just sucking in that air.”

Barlow explained that it was very important to go deep because the deeper you went, the greater the water pressure. The water pressure would condense the size of the blast, meaning of course that to damage the boat, the depth charge would have to be much closer to the boat. This also meant that the explosion would be magnified by the increased water pressure. The deeper water offered further protection for the same reason that it is harder to find a minnow in a river than a shallow creek. Finally, at 1000 hours, in the heavy rain, the distant echo ranging died out. The men on board could breathe a deep sigh of relief. Gudgeon had nearly been destroyed, but the tiny pest that packed such a huge wallop was gone. Repairs began immediately. After the attack, a crumpled piece of paper was found in the wastebasket in Gudgeon’s control room. On it someone had written, then tossed into the garbage can the following, “I wish to hell we had wings sometimes—sometimes!!!”

Once again Shirley Stovall was proud of his veteran crew. Stovall commented that about “75 percent of the gauges and lights throughout the ship were broken; the entire ship was pretty badly shaken around. However, the crew took it splendidly; it was nothing new to them, they had had close depth charging before and they had always stood up in an excellent fashion.”

With Gudgeon’s crew licking their wounds, the submarine moved slightly south. For several days Gudgeon patrolled far off Ambon Bay, all the while working on repairs. Damage was severe throughout the submarine, quite a lot more so aft than forward. Among the items that were broken or damaged were the emergency freshwater tanks, inclinometers, gyro, QC sound head shafts, depth gauges, and one of the propellers. There were air, hydraulic, oil, and water leaks. Various units on the Gudgeon shook and vibrated and did not work as they were supposed to. Of great alarm was the fact that only two of the submarine’s ten torpedo tubes were functional.

As stated in Mike Ostlund's description above: "Most sobering of all was the dished-in hull in the after torpedo room; this damage confirmed that the charge was at about Gudgeon’s depth and close aboard, starboard of that compartment, and had all but ruptured the submarine’s hull. Miraculously, electrician’s mate John L. Cadman was the only man to have sustained a wound." Aboard Navy vessels, every crew member has a "general quarters" (GQ) station or battle station. When a naval action is imminent, such as an enemy attack, the call of "general quarters, general quarters" goes out indicating all hands must man their battle stations. In some cases, general quarters stations are the same as a normal work station but often a crew member must occupy a different location and perform a different task than is his normal assignment. As indicted in his service record below (Figure 20), John Cadman's general quarters station on the Gudgeon was the after torpedo room acting as a loader. When general quarters was called out during the Ambon attack, John would have proceeded to his battle station. He would have been there when the after torpedo room hull was caved-in. It is hard to image the noise, shock, and concussion he would have experienced when that charge went off.

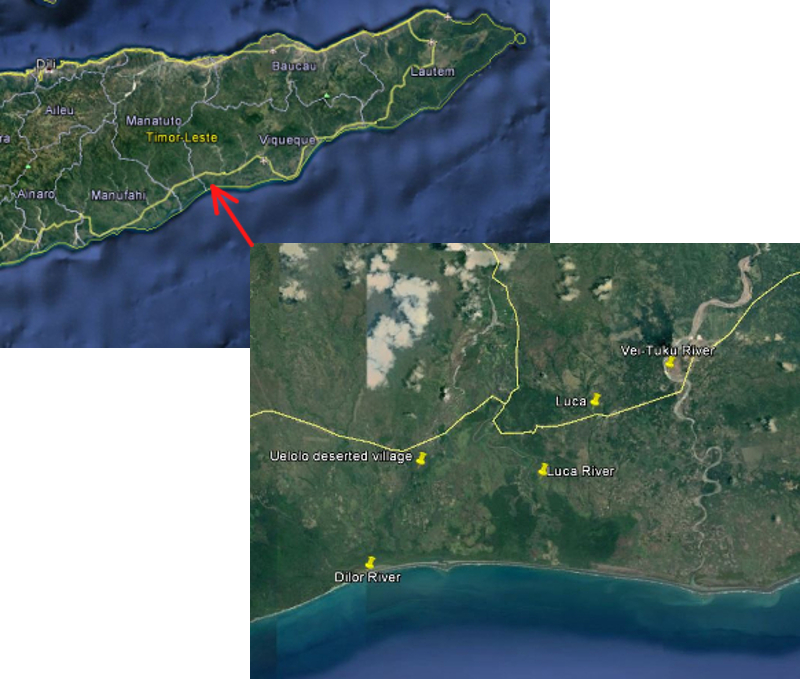

Commando Rescue

Meanwhile, the Holland/Broadhurst commando group had been moving in a southwesterly direction through the eastern end of the island (then known as Portuguese Timor) desperately trying to stay ahead of Japanese troops pursuing them with horses and large dogs. The commandos had to deal with intense rain while traversing dense undergrowth and steep mountainsides bordered by deep gorges (Figure 21). Many of the natives that accompanied them had fled in fear of being captured and tortured and took weapons and ammunition with them. Because allegiances were changing in recognition that the Japanese might soon be the the only rulers on the island, many of the natives they encountered along the way became less than friendly and provided little information about Japanese locations. Eventually Holland encouraged the remaining natives to scatter for their own safety and the safety of the commandos. Supplies were running low and food was being strictly rationed.

As Japanese encountered locations where the commandos had camped overnight, they slaughtered men, women, and children and burned the villages and encampments to the ground. Several times the commandos were virtually surrounded by the Japanese only to escape by moving along creek beds in order to leave no signs that would allow the Japanese and their dogs to track them.

On the evening of the 23rd the commando group came upon the Vei-Tuku River (Figure 22) and found that only 500 yards upstream a fire was burning at a Japanese encampment. Everyone who was wearing boots took them off so no boot marks would be left as they moved along the river for the remainder of the night.

On the 27th the commandos reached the village of Luca where they met up with a group of Portuguese who were also fleeing the Japanese. At that point their radio, which had been damaged along the way, could only transmit but not receive. They sent a message to command headquarters in Darwin to ask them to constantly monitor their frequency and air drop another radio so the could coordinate their escape efforts and they proceeded on to the a deserted village known as Uelolo. After stopping there for a short time to rest and bath, they learned that the Japanese had crossed the Luca River and the commandos were forced to move on in a hurry.

At sea on January 31, the Gudgeon had spotted a Japanese destroyer heading in the opposite direction at 15,000 yards. The ship was moving at too high of a speed for the Gudgeon to close and soon disappeared. Later the same day, a plane spotted their periscope and got in close to drop "two heavy objects" which did not explode. The crew speculated that they were depth bombs or depth charges that were duds. After some additional looking, the Gudgeon moved south to patrol in the area of the Banda and Kai Islands.

On February 3rd, while stopping to rest, the Holland group encountered a second group of Australians known as the Lancer commando group that had also been fleeing the Japanese. The Lancers had lost 5 five men and their radio along the way. The two groups decided to join up and continued on.

By that time, several attempted air drops to the commando group had been unsuccessful, largely because of the malfunctioning radio. That evening some dropped parachutes were located with food and batteries but the wireless radio that was dropped could not be found. Later, on February 6th, a low-flying Hudson successfully dropped food and two radios. At that point the commandos had been able to put some distance between them and the Japanese but by the seventh or eighth, the Japanese were again hot on their trail.

Meanwhile, passing through the Wetar Passage of the Indonesian Islands, the Gudgeon encountered another small ASW patrol boat similar to the one that had done them harm off Ambon, but this time they weren't attacked. At 1200 on the 8th, not having fired at a single target during the patrol, LCDR Stovall made the determination that the damage they had sustained at Ambon was compromising their effectiveness and making them too vulnerable to attack and so he directed the sub to head home. On the 9th, the Gudgeon received a message that they were to execute an evacuation of the commando team as they passed by Timor.

On Timor, the Holland/Broadhurst group had reached the Dilor River and moved south through a mangrove swamp far enough to halt just short of the open sea. The swamp, with it's miserable combination of mosquitos and water to the waist, had made the travel slow and taxing but encouraged Holland in that he felt that the conditions made it very difficult for the Japanese to locate and access the commando group. Late on the 9th, they received a message from Australian headquarters that they were to be evacuated the following day and that they were to display a white shirt visible to the vessel that would be picking them up. Although no white shirts were available, one of the accompanying natives did have a white cloth that they rigged up on two bamboo poles and set up on the beach at a location visible from the sea but not to the Japanese in the nearby villages of Beaco and Kicras.

LCDR Stovall had been reconnoitering the coast for several days and using landmarks to help locate Australians. On the 10th he had found the general location and was able spot the white cloth. After monitoring the cloth for several hours and scanning the beach above and below for signs of Japanese presence, he made the decision to do the pickup after sundown the same day.

Over the radio, Darwin had coordinated the recognition signals to be flashed from the Gudgeon ("C") and from the commandos ("Z"). After dark, two Hudson bombers flew overhead and dropped bundles of rubber boats, lifebelts, and coils of rope with cork attached so the commandos could retrieve them as they floated on the water (Figure 23). Unfortunately, they were only able to retrieve two serviceable rafts for the 28 men they needed to evacuate.

At 1907, the Gudgeon and the commandos exchanged recognition signals. At 1945, Gudgeon came to rest a half-mile off the beach. At 2002, the first group from the beach came aboard. Upon their arrival, the shortage of rafts was discovered and it was decided that three seven-man rubber boats that the Gudgeon had standing by would be taken ashore by four sailors from the Gudgeon crew. This increased capacity enabled the addition of a Portuguese officer that had joined the commandos and five of the natives to the twenty-three Australian and English commandos included in the evacuation.

From Mike Ostlund's narrative:

Two of the four crew members had to make two round trips to secure all of the evacuees, which extended the time the operation remained vulnerable to Japanese discovery. On the first trip they had left a submachine gun with Broadhurst and the second return of the rafts was taking so long that he was afraid he would have to use it. Broadhurst said later: "“We believed that the craft had been forced to leave. We began clearing the beach when to our joy a signal flashed out and shortly afterwards two of the large rubber boats came in. We set out through the surf and one boat capsized. Our natives could not swim, and for a few moments we had great difficulty in getting them ashore and setting out again. This time we rode the surf successfully."

Before the last raft arrived back at the Gudgeon, her four diesel engines were running and ready for departure. At 2225, the last raft finally arrived and the rafts were deflated and shoved down the hatch, followed by those still on deck. At 2229, the Gudgeon pulled away.

The capture of Timor by the Japanese was a significant blow to the Allies and particularly to the Australians because of Timor's strategic proximity to the Australian continent. But the efforts of the commando and guerrilla operations during the rest of the war resulted in an estimated 1000 Japanese casualties and prevented critical Japanese assets from participating in the greater war effort. The Gudgeon's extraction of the Holland/Broadhurst commandos contributed to those efforts.

Return To Freemantle

The Gudgeon departed Timor with ninety-two men aboard, including twenty-eight under-nourished, injured, and diseased (malaria was common) men. Their obvious hardships brought home to the crew the sacrifices that others were undertaking in the fight against the Japanese. Exposure to these men's aliments put all those on board at risk but none of the Gudgeon's sailors complained. On February 18, 1943, after 53 days at sea, the Gudgeon's 6th war patrol ended when she reached port in Freemantle and moored alongside the submarine tender Pelias.

The lack of success in interdicting Japanese shipping during the 6th war patrol garnered some criticism of LCDR Stovall for not being aggressive enough in seeking out targets - the Gudgeon had only sighted six ships, all naval vessels rather than merchants, and only two had been deemed potential targets. Regardless, the Gudgeon was awarded her sixth straight Battle Star and its crew was praised for its efforts in supporting the Villamor landing and the successful evacuation of the Holland/Broadhurst commandos. Upon nomination by LCDR Stovall, the four crew members who had gone ashore to rescue the commando group were awarded the Navy and Marine Corps Medal.

The attack and near sinking of the Gudgeon by the small Japanese patrol boat off Ambon provided some important intelligence to the ranks of the Silent Service. LCDR Stovall was impressed by the excellent sound gear of the patrol boat which indicated possible ongoing improvement in Japanese ASW capabilities. In addition, the fact that the patrol boat had set its depth charges at much greater depths (250-300 feet) than was normal in Japanese ASW operations caused the American submarine community to rethink their evasion tactics.

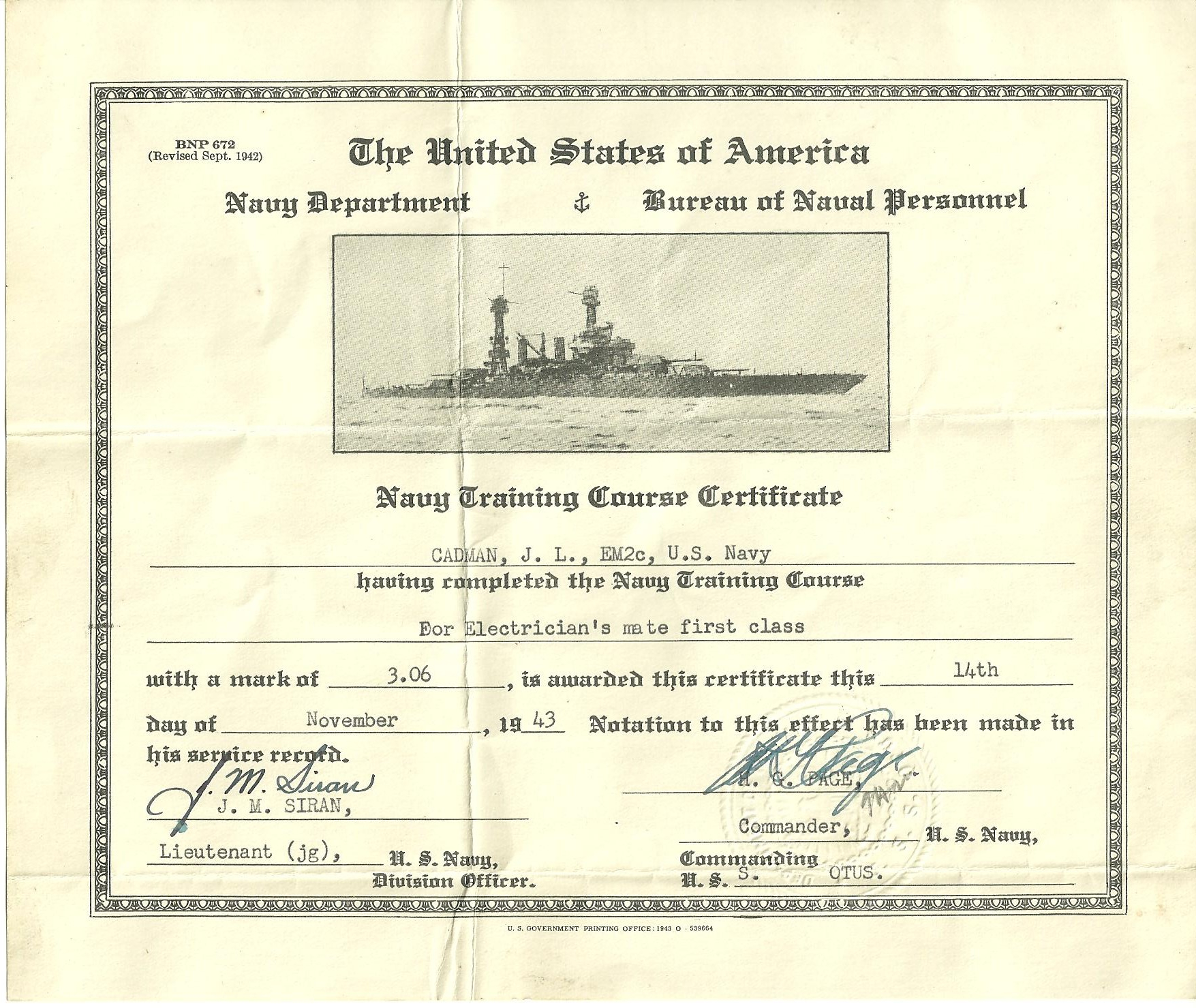

On February 1, 1943, John Cadman received a Unit Commendation from LCDR Shirley Stovall and attained the rate of Electricians Mate 2nd Class (EM2). This would prove to be the last war patrol he would undertake as a member of the Silent Service.

Up to this point in the war, John Cadman had been engaged in war patrols on two different submarines: USS Trout and USS Gudgeon. A total of 52 US submarines were lost in WWII. The U.S. Navy's submarine service suffered the highest casualty percentage of all the American armed forces, losing one in five submariners. Some 16,000 submariners served during the war, of whom 375 officers and 3131 enlisted men were killed. Both the Trout and the Gudgeon were among the 52 along with the entire crews manning them at the time that were lost. It is hard to imagine what John must have felt upon learning of those losses.

Sinking of the USS Trout

The loss of the USS Trout is described as follows on the website On Eternal Patrol:

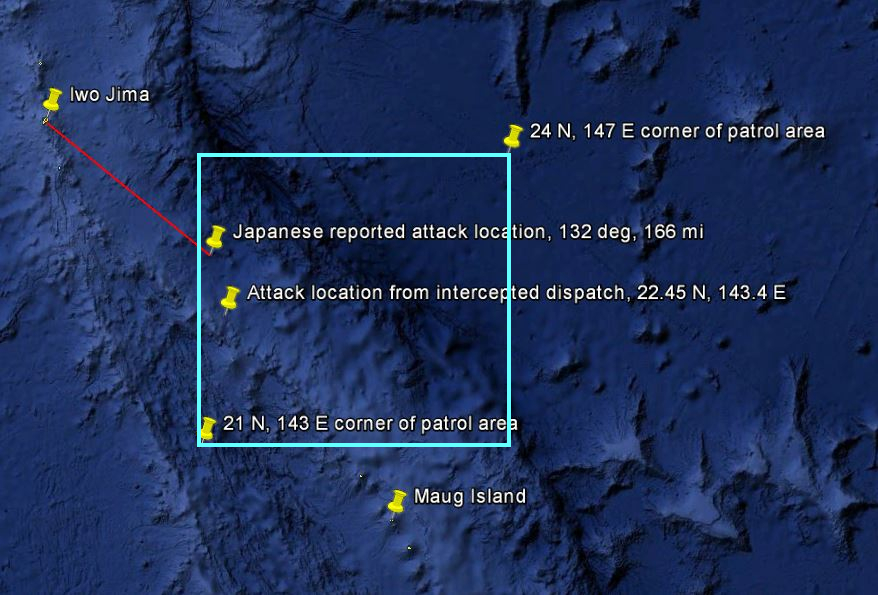

The veteran patroller TROUT (LCDR A. H. Clark) left Pearl Harbor on 8 February 1944, enroute to her assigned area for her eleventh patrol. She topped off with fuel at Midway and left there on 16 February, never to be heard from again. She was to patrol between 20° 00'N and 23° 00'N, from the China coast to 130° 00'E. TROUT was scheduled to leave her patrol area not later than sunset on 27 March 1944 and was expected at Midway about 7 April 1944. When she did not arrive, she was reported as presumed to be lost on 17 April 1944.

From information received from the Japanese since the close of the war, the following facts have been gleaned. On 29 February 1944, SAKITO MARU was sunk and another ship badly damaged in position 22° 40' N, 131° 45' E. TROUT is the only U.S. submarine which could have made an attack at this time in this position (Figure 24). Since TROUT did not report this action, it is assumed that she was lost during or shortly after this attack.

Sinking of the USS Gudgeon

As he noted in his book, 'Find 'Em, Chase 'Em, Sink 'Em: The Mysterious Loss of the WWII Submarine USS Gudgeon', Mike Ostlund was motivated to write it by the presence of his uncle LTJG William C Ostlund on board the Gudgeon when it was lost and by the desire to tell the story of one of the most decorated submarines in WWII. But he also hoped to uncover a clearer picture of where and how the Gudgeon met its end. The latter turned out to be an interesting detective story:

Mike's research started with a book his brother found at a garage sale that stated:

He then found several other books that addressed the Gudgeon sinking:

The patrol area that the Gudgeon was assigned to on April 18, 1944 was located northwest of Maug Island in the northern Mariana chain and southeast of Iwo Jima. "Maug" did not seem to be a likely match for "Yuoh" but Mike noticed that "Yuoh Jima" sounded very similar to "Iwo Jima" and found that "jima" is another word for "island" in Japanese. Further investigation revealed that "yuo" was the Japanese word for "sulfur" so "Yuoh Island" was effectively "Sulfur Island" (with an incorrect phonetic spelling of "yuo"). That corresponded to the fact the Iwo Jima is a volcanic island with active and noticeable emissions of sulfur, indeed the word "iwo" is Japanese for sulfur so Yuoh Island was in fact Iwo Jima.

Further research revealed that the Japanese had located an ASW unit on Iwo Jima. Mike was put in touch with a retired Japanese Navy captain, Noritaka Kitazawa who was affiliated with the National Institute for Defense Studies located in Tokyo:

He sent several photocopied handwritten pages from the war diary of the “Chichi-Jima Houmen Advanced Base Group” for the time around April 18. Chichi Jima is an island just north of Iwo Jima. The term “Houmen” suggests that the Chichi Jima base was administratively responsible for the antisubmarine units on Iwo Jima.

Captain Kitazawa translated the material and paraphrased it for me. In his letter dated August 30, 2001, Captain Kitazawa wrote: “War diaries of the 901st Kokutai in this archive has no records concerning this case, but War Diary of the Chichi-Jima Houmen Advanced Base Group contains some records of this attack. According to the War Diary of the Chichi-Jima Houmen Advanced Base Group, No. 1 aircraft of Iwo-Jima dispached [sic] team from 901st Kokutai reported 0845 JST (Japanese Standard Time) 18th April that Bombed Enemy Sub. 132˚ Iwo-Jima 166 Nautical miles, Sunk certainly 0630.”

He continued, “And according to the same War Diary, at 1815 JST from Commanding officer of Iwo Jima dispached team was reported that No. 3 aircraft of No. 1 subdivision which took off 0500 from Iwo-Jima, at 0630, on 132˚ Iwo-Jima 166 Nautical miles. Bombed an Enemy Sub. Just after his submergence, with two 250 kg bombs. And 1st bomb hit sub’s head and 2nd bomb hit sub’s bridge straight, and the aircraft sighted on the center of hull to spring big yellow-green explosion, and to spring up tall oil piller [sic] and enlarged thick crude oil circle about 150 meters in diameter, so this target evaluated sinking.”

The Japanese records confirmed that the attack was 166 miles, at 132˚ T off Iwo Jima. The 250-kilogram bombs that had been used in the attack were massive, each weighing around six hundred pounds.

A second letter was received a few weeks later. Captain Kitazawa explained that he had reread the material and concluded that only one aircraft was involved in the attack. He had misunderstood the old diaries. He could find no additional information or the names of the crew involved in the attack.

I made contact with Rick Dunn, an expert on Japanese aircraft during the war, who found a dispatch from the 901 Kokutai for April 20 that gave the specific location for an attack that had occurred on a U.S. submarine on the eighteenth. The dispatch stated that the attack took place at 22-45˚ N, 143-40˚E. The distance from Johnston Island located at 16.45˚ N, 169.31˚ W to this proposed sinking site is around 2,700 nautical miles. Could Gudgeon have made it to the proposed sinking sites by April 18? The Chief of Naval Operations (in United States Submarine Losses World War II) indicated that Gudgeon would have been in her assigned patrol area as early as April 16 if nothing unusual had been encountered en route.

Although the submarines of the Silent Service suffered significant losses during WWII, they were instrumental in opposing Japanese aggression in the early months after Pearl Harbor and went on to inflict devastating damage to the Japanese merchant fleet and the Imperial Japanese Navy. By the end of the war, the Japanese merchant tonnage was one quarter of what it was in 1941. US submarines were responsible for 55% of that reduction in the course of sinking an estimated 1300 Japanese merchant ships. The USS Gudgeon was credited with being the first US Navy submarine to sink an enemy warship in World War II and the Silent Service was credited overall with sinking 200 Japanese warships. In the words of Fleet Admiral Chester Nimitz, USN: "We shall never forget it was our submarines that held the lines against the enemy while our fleets replaced losses and repaired wounds."

At the end of Mike Ostlund's book, he offers, in the Afterword, the following thoughts regarding all of the men who served on the Gudgeon, including John Cadman:

What a great opportunity this was to learn about the Gudgeon and the men who served on her with my uncle. How often does a person get to mingle with truly heroic men? How can one who has never lived through the Great Depression understand what those men went through? How can one who did not ride Gudgeon even “touch” those experiences? What was it really like when Gudgeon moved slowly past the sunken fleet in Pearl Harbor toward Japan to finally settle alone, deep in the waters off Japan? How can anyone who was not present understand what it was actually like to have undergone the soul-shaking depth charge attack off Ambon? Or Truk Island? Can anyone really know what it was like to have your submarine, considered to be a loved being by those who served on her, sunk, taking countless former friends and loyal shipmates with her to the bottom, somewhere, somehow in the spring of 1944? How can one comprehend how difficult it was to once again pick one’s self up and continue serving, knowing full well that any day it could be your turn to go? Will we ever know what it was like to be nineteen, twenty, or even fifteen years old standing on the deck of a World War II submarine as the shells of Japanese gunners are flying past your head? Can we comprehend the exhilaration of sinking one of the submarines that helped carry out the attack at Pearl Harbor or the rather gruesome thrill of sending thousands of your sworn enemy to the bottom as compensation for the horrors they had inflicted upon your countrymen?

It is impossible to know. It can only be sought, and if one is lucky, it can be touched so that in some way, while it is being acknowledged at the thinking level it is also being felt in the heart.

US Navy Pacific Surface Fleet

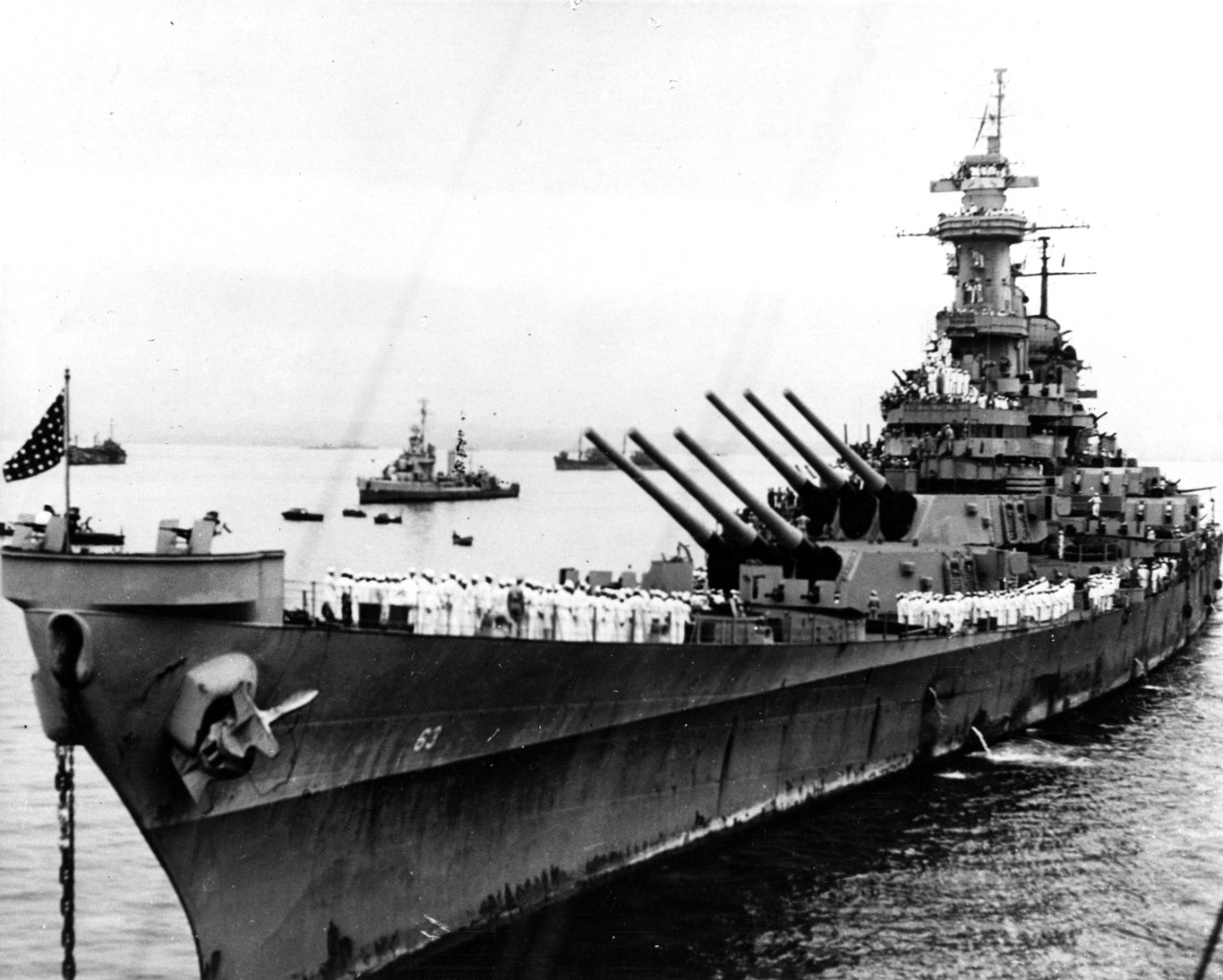

After serving two war patrols on the USS Gudgeon, John Cadman's next major duty station was to be the Navy's brand new battleship USS Missouri (BB-63), still under construction at the Brooklyn Navy Yard, New York.

USS Missouri (BB-63)

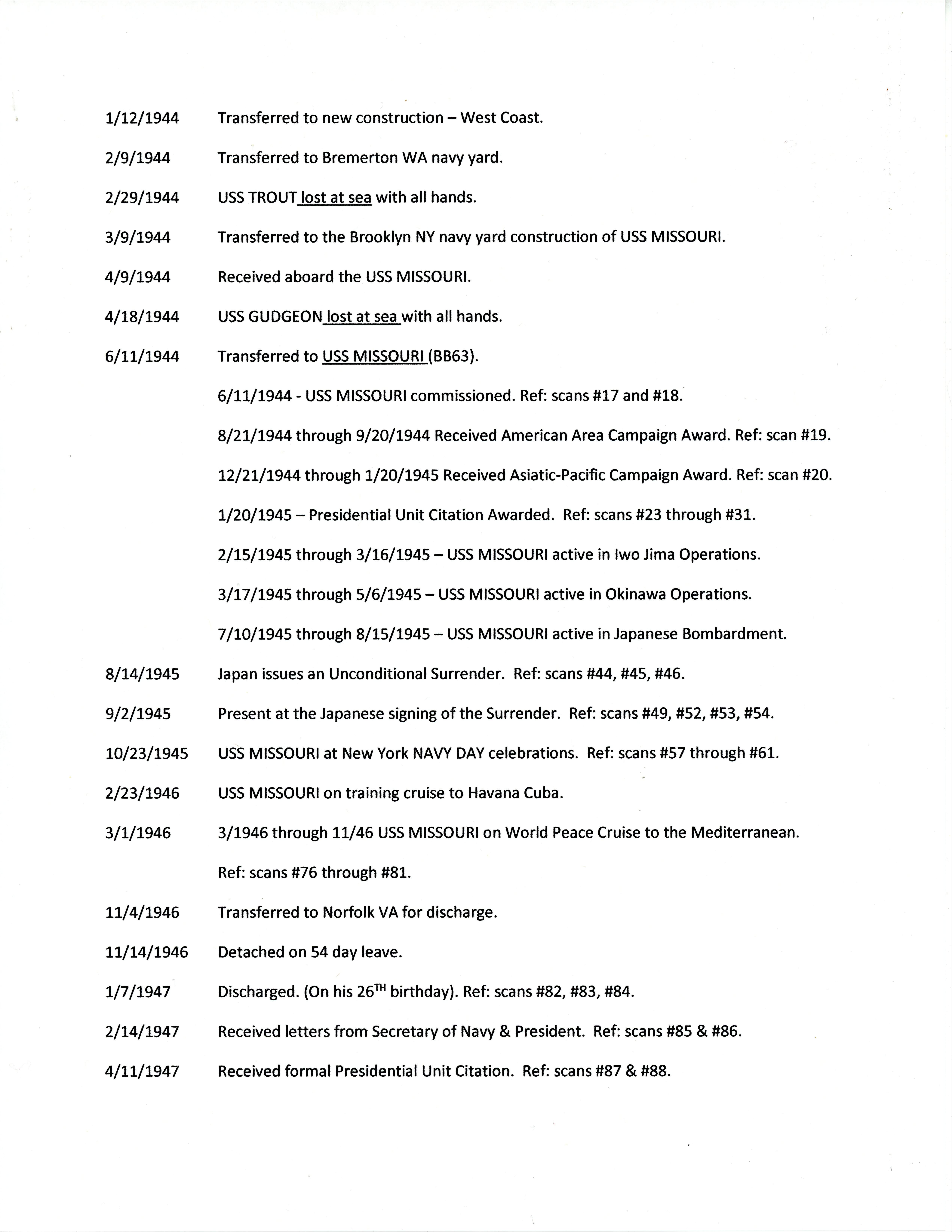

Before becoming a member of the USS Missouri's crew, there were a few intermediate steps along the way. Thanks to Dennis Cadman's "Chronology of Service", we know what those steps were:

- March 3, 1943 - transferred to the submarine USS Triton (SS-201) relief crew.

- May 15, 1943 - transferred to submarine tender USS Otus (AS-20).

- November 11, 1943 - attained the rate Electrician's Mate 1st Class (EM1).

- December 2, 1943 - received a Unit Commendation from the commander of the USS Otus.

- January 12, 1944 - transferred to new construction on the west coast.

- February 9, 1944 - transferred to the Bremerton, Washington navy yard.

- March 9, 1944 - transferred to the Brooklyn, New York navy yard (ongoing construction of the USS Missouri).

- April 9, 1944 - received aboard the USS Missouri.

- June 11, 1944 - USS Missouri commissioned. EM1 John Cadman's transfer to the USS Missouri was made official upon the commissioning.

The Missouri is Launched and Prepared for Battle

After sea trials, a shakedown cruise, and battle drills in Chesapeake Bay from August 21 through September 20, 1944 (Figure 29), John Cadman was awarded the American Area Campaign Medal. This medal was created through an executive order by President Franklin D Roosevelt to recognize military service in the American Theater of Operations during World War II.

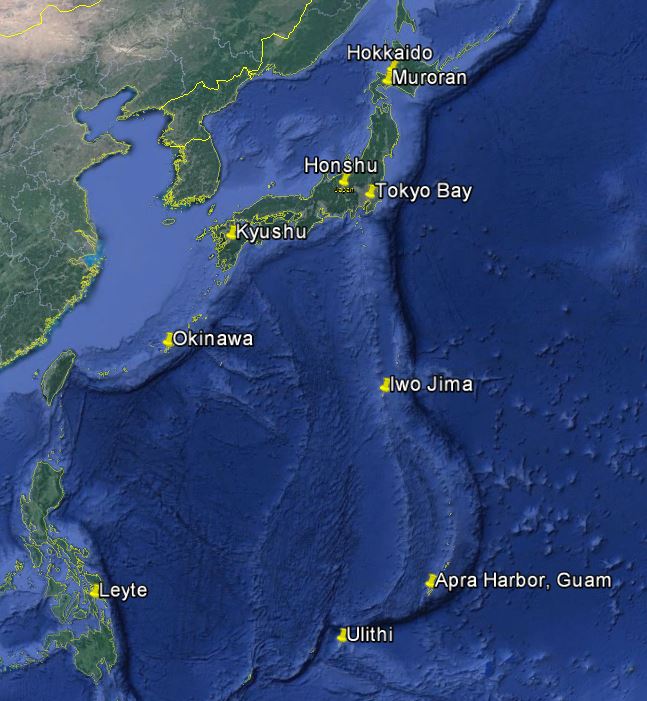

Back to the Pacific

On November 11, 1944, Missouri departed Norfolk, Virginia and steamed toward San Francisco for a final fitting out. On November 18, she transited the Panama Canal (Figure 30). On December 14, 1944 she left San Francisco Bay and headed to Pearl Harbor, arriving on December 24. On January 2, 1945, Missouri departed Hawaii and headed toward the western Pacific to serve as the temporary headquarters ship for the Task Force 58 Commander. She arrived in Ulithi, West Caroline Islands on January 13 (Figure 32). For this period of service, John Cadman was awarded the Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal for service in the Asiatic-Pacific Theater under criteria similar to his American Campaign Medal.

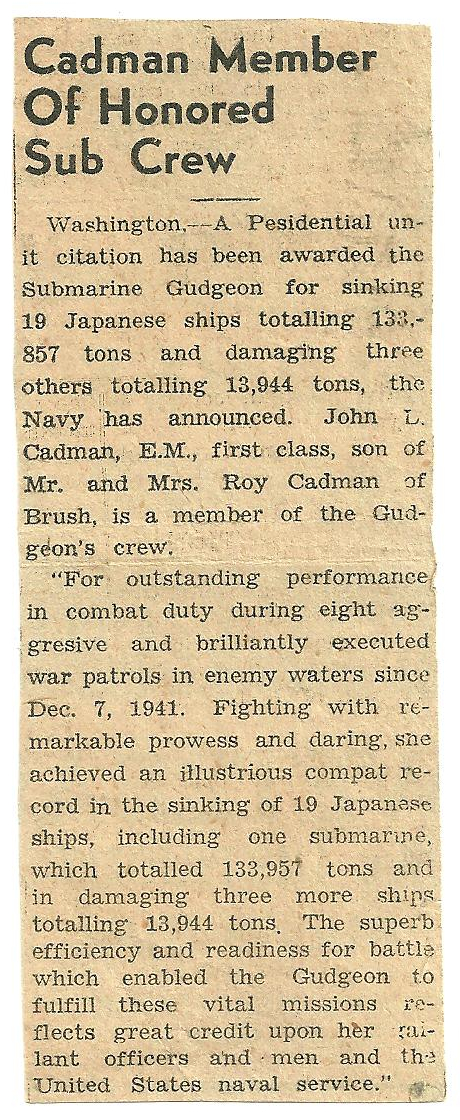

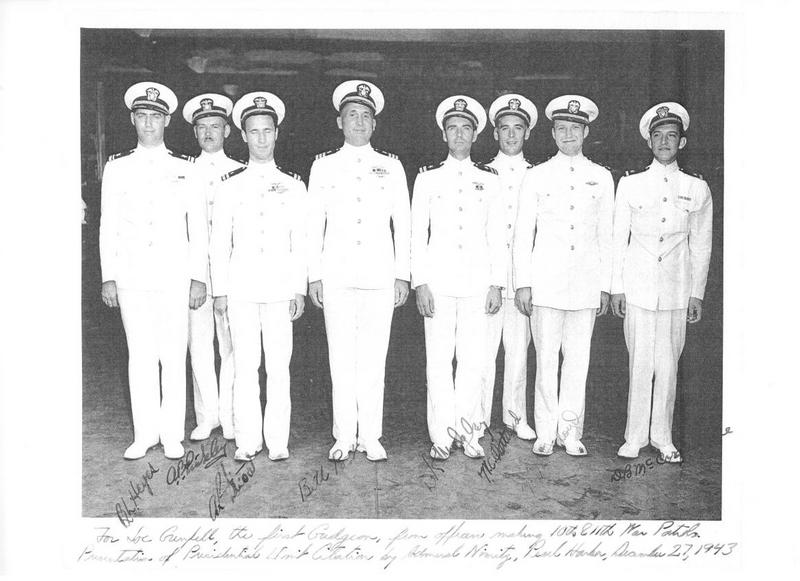

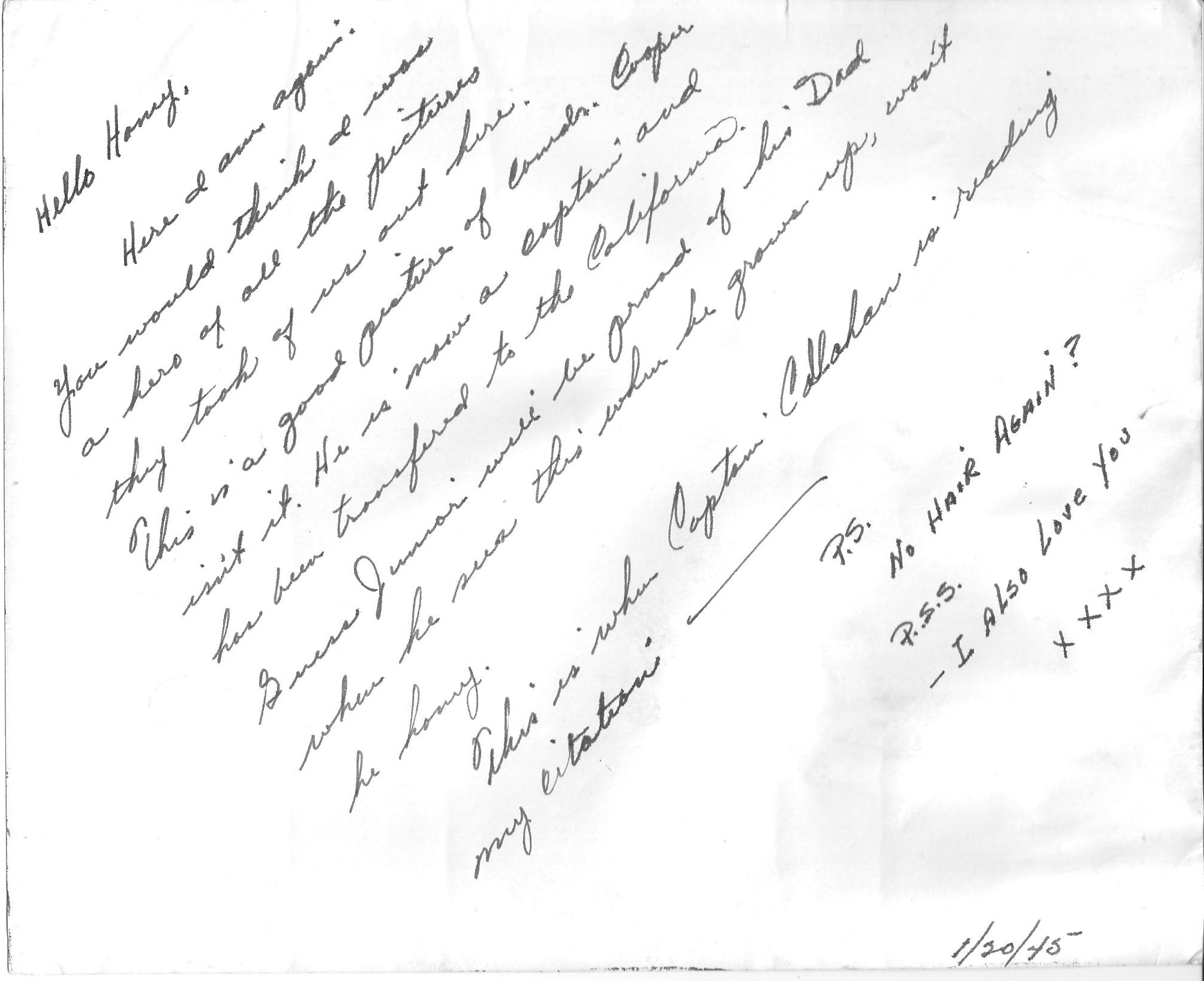

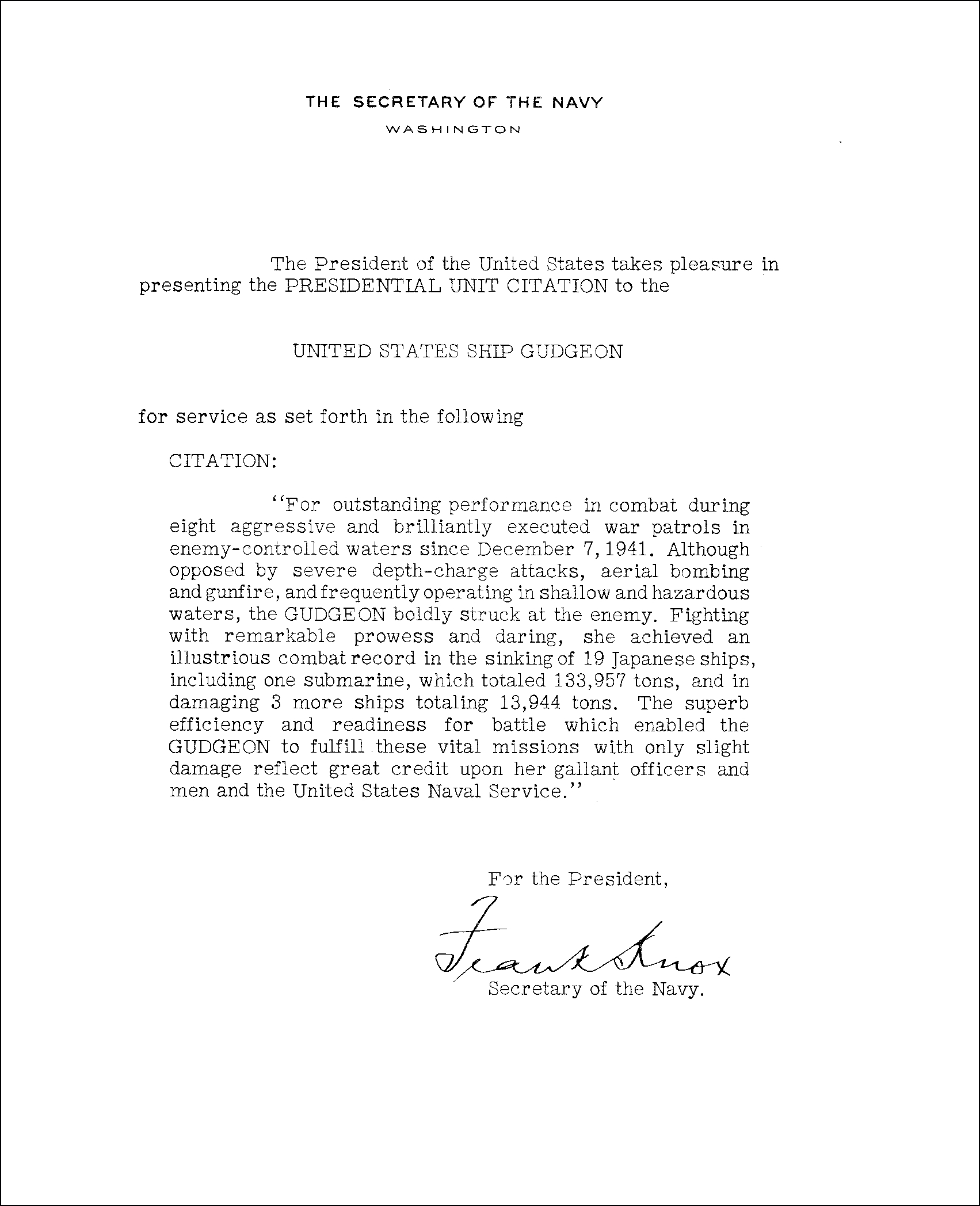

The Presidential Unit Citation

On January 20, 1945, while the Missouri was still in port at Ulithi, John Cadman was presented with a Presidential Unit Citation in a formal ceremony on board the ship (Figures 33 & 34). The PUC is awarded to units of the uniformed services of the United States for extraordinary heroism in enemy action on or after December 7, 1941. The PUC is the unit equivalent of the Navy Cross awarded to individual Navy and Marine Corps service members. According to news releases (I don't have a copy of the actual award text) John's award was for his service on the USS Gudgeon (the unit) in February of 1943. In February of 1943, the Gudgeon was engaged in the rescue of Australian and English commandos from the island of Timor (see above). John was also authorized to wear a silver star on his ribbon decoration, signifying that this was the second PUC that the Gudgeon had received. The first PUC was awarded to the Gudgeon crew in a ceremony at Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1943 (Figure 37). This was after the time that John had left the Gudgeon so he was not present at that ceremony, but the award was in recognition of the Gudgeon's performance during its first eight war patrols after Pearl Harbor. John was on board the Gudgeon for the fifth and sixth war patrols (see above). In receiving the second PUC, John was representing the crew on the Gudgeon which had been lost at sea with all hands ten months previously on April 18, 1944 during its twelfth war patrol.

The Missouri Goes to War

For her first enemy engagement, the Missouri was assigned to the Lexington aircraft carrier task group of Task Force 58. The Missouri was armed with 129 anti-aircraft guns which provided formidable defense against enemy aircraft attacking the carrier task group. On January 27, 1945 the Missouri departed Ulithi, and on February 16 the task group's carriers launched the first naval air strikes against Japan since the Doolittle raid.

Bombardment of the Japanese home islands was curtailed when the task group was directed to proceed south to provide support for the battle of Iwo Jima. Starting on February 19, the Missouri provided naval gun bombardment to soften the heavily defended island in advance of the Marine assault. The video in Figure 39 was produced by the US Navy to illustrate how the pre-assault offensive was conducted and the key contributions of the naval heavy gun bombardment. Although the Missouri is not explicitly mentioned in the video, she was an integral part of the operation and the actual footage of the battle included in the video is indicative of what John Cadman experienced as part of the Missouri crew.

After Iwo Jima, Missouri returned to Ulithi on March 5 and was assigned to the Yorktown carrier task group. Her mission was to provide anti-aircraft screening for the task group as it steamed toward the Japanese mainland. In the course of providing support for strikes along the coast of the Inland Sea of Japan, Missouri shot down four Japanese aircraft.

The Yorktown task group returned to Ulithi on March 22 and, by March 24, Missouri had left port and arrived at Okinawa to provide naval gun bombardment in support of the planned invasion. After the landing on April 1, she maintained off of Okinawa to provide ongoing naval support. At approximately 1400 on April 11 she was attacked by a low-flying Kamikaze aircraft which managed to evade the Missouri's guns and impact the ship on the starboard side just below main deck level (Figure 41).

Following is the account of the photographer (Harold "Buster" Campbell - ship's baker and unofficial photographer) who took this picture:

"Well this day will live forever in my memory as the most exciting incident I've ever experienced! Pat and I were in the Photo Lab. 1404 the "Air Alert" was sounded and we both ran up to the bridge [08 level] and broke out our cameras. I used the K-20 as always and Pat the F-56. Well we saw a bit of firing on the horizon, then the Jap planes entered our area and all the ships in our Task Group opened up. We hit one and he exploded, I got a few shots [photographs]. While we were shooting this one, another came up off our stern. I got him in the sight of my K-20 and started shooting shots. He kept coming in through the greatest ack-ack [anti-aircraft gunfire] I've ever seen. 5", 40's and 20mm; about 100 yards off the starboard quarter he was hit slightly but kept coming. I keep shooting pictures. He then banked toward the ship about 25 ft above the water. I had taken approx 10 shots since I picked him up. He then came direct at the ship and hit us on the starboard quarter on the main deck, burst into flames. I was shaking but felt relieved after he hit. I took a beautiful shot of him as he hit and several as he came burning all along the starboard side till he ended at Mt. #1 [5" gun mount]. All in all I got 18 shots. Poor Pat was in back of me and couldn't get a thing. They put out the fire and believe it or not, we didn't have a single casualty, not a person was hurt. This I really believe is a miracle as I'll get the pictures to show just what happened. It only lasted about 5 minutes but it sure was something to see."

And here is the account of Captain Roland W. Faulk, a Commander on board the Missouri at the time:

"...Following the sinking of Yamato, it was obvious that for a time, prime targets of Japanese kamikazes were the battleships. Thus on April 11, 1945, we had our first kamikaze hit. I happened to be making my way up the inside ladder of the superstructure to the navigation bridge and just as I stepped out into the cross-passageway I was almost trampled in a rush of officers and men moving from the starboard to the port side of the bridge.

Their action was prompted by the sight of a kamikaze coming from directly astern and apparently headed for the bridge. The young Japanese pilot had obviously chosen to make his run to death by coming in low – just above the water. He was picked up when he was two or three miles astern and all the guns that could be brought to bear were firing at him, not only from Missouri but from other ships in the formation.

The members of the forty millimeter gun crews on the stern described to me the way the plane came in. The pilot had apparently been untouched by the hail of gunfire and was riding his plane in like a jockey on a race horse - squatting in his seat. He hit just abaft of turret three, shearing off the port wing of the plane which flew a hundred feet forward and landed behind a five inch gun mount at an intake vent which provided ventilation to the fire rooms. His torso fell on the main deck and the whole rest of his plane and portions of his body went into the water - all without a bomb exploding.

The next morning a military funeral was conducted for the Japanese pilot who appeared to be a young man about eighteen or nineteen years of age. To some of the crew who grumbled because military honors were rendered, I reminded them that a dead enemy is no longer an enemy. As far as I was aware, this was the only instance of its kind in World War II where such honors were rendered under such circumstances."

Missouri continued support of the Okinawa operation through the end of April and into early May. During that period she experienced another Kamikaze attack (aborted by gunfire) and participated in an ASW operation that resulted in the sinking of Japanese submarine I-56. On May 5, Missouri departed the Okinawa area and headed for Ulithi and on from there to Apra Harbor, Guam where Admiral William F Halsey, Jr. of the 3rd Fleet brought his flag aboard. She departed Guam to conduct the following operations for the next 2 months:

- May 27 - conducted bombardment of Okinawa

- June 8 - conducted bombardment of Kyushu, Japan

- June 13 - conducted bombardment of Leyte, Philippine Islands

- July 8 through August 9 - performed screening for the 3rd Fleet's carriers

- July 13 and 14 - Supported carrier strikes on Honshu and Hokkaido, Japan

- July 15 - attacked the facilities of the Nihon Steel Company and Wanishi Ironworks at Muroran, Hokkaido (first time Naval gunfire destroyed a major installation on the Japanese home islands)

- July 17 and 18 - conducted nighttime bombardment of industrial targets on Honshu

- July 19 through July 25 - continued to support carriers conducting air attacks on the Japanese home islands

- August 9 - Resumed support of strikes on Hokkaido and Honshu on the day the second atomic bomb was dropped on Nagasaki

The Japanese Surrender

After hearing rumors of impending Japanese surrender on August 10th, the official announcement to the crew came on August 15, the same day that the Japanese Emperor Hirohito used a recorded radio broadcast to announce the surrender to the people of Japan. Following is a transcript of that broadcast:

After pondering deeply the general trends of the world and the actual conditions obtaining in Our Empire today, We have decided to effect a settlement of the present situation by resorting to an extraordinary measure.

We have ordered Our Government to communicate to the Governments of the United States, Great Britain, China and the Soviet Union that Our Empire accepts the provisions of their Joint Declaration.

To strive for the common prosperity and happiness of all nations as well as the security and well-being of Our subjects is the solemn obligation which has been handed down by Our Imperial Ancestors and which lies close to Our heart.

Indeed, We declared war on America and Britain out of Our sincere desire to ensure Japan's self-preservation and the stabilization of East Asia, it being far from Our thought either to infringe upon the sovereignty of other nations or to embark upon territorial aggrandizement.

But now the war has lasted for nearly four years. Despite the best that has been done by everyone—the gallant fighting of the military and naval forces, the diligence and assiduity of Our servants of the State, and the devoted service of Our one hundred million people—the war situation has developed not necessarily to Japan's advantage, while the general trends of the world have all turned against her interest.

Moreover, the enemy has begun to employ a new and most cruel bomb, the power of which to do damage is, indeed, incalculable, taking the toll of many innocent lives. Should we continue to fight, not only would it result in an ultimate collapse and obliteration of the Japanese nation, but also it would lead to the total extinction of human civilization.

Such being the case, how are We to save the millions of Our subjects, or to atone Ourselves before the hallowed spirits of Our Imperial Ancestors? This is the reason why We have ordered the acceptance of the provisions of the Joint Declaration of the Powers....

The hardships and sufferings to which Our nation is to be subjected hereafter will be certainly great. We are keenly aware of the inmost feelings of all of you, Our subjects. However, it is according to the dictates of time and fate that We have resolved to pave the way for a grand peace for all the generations to come by enduring the unendurable and suffering what is unsufferable.

The next day Admiral Sir Bruce Fraser, Commander of the British Pacific Fleet, boarded the Missouri to award Admiral Halsey the Order of the Knight of the British Empire.

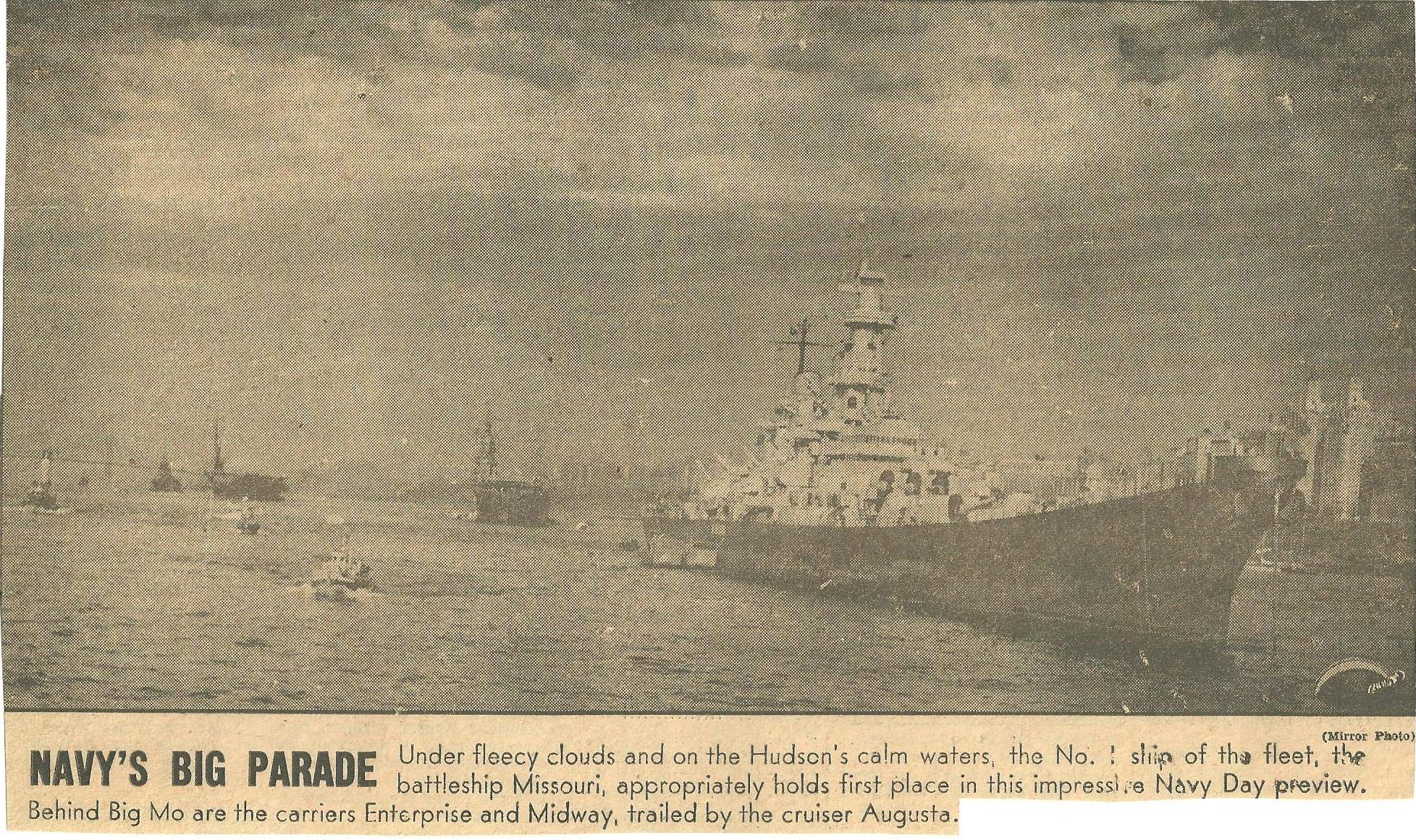

President Truman selected the Missouri (named after his home state) for the formal Japanese surrender ceremony. On August 20, in anticipation of the ceremony which was to take place in Tokyo Bay, a 200-men party from the Missouri was transferred to the USS Iowa for temporary duty with the Tokyo occupation force (Figure 44).

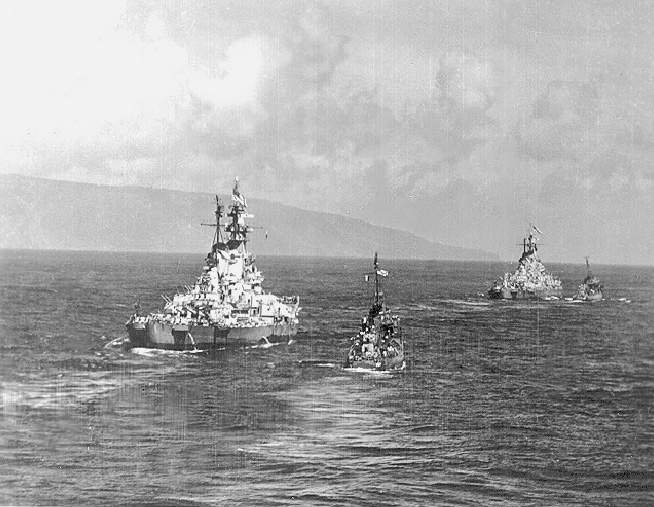

Early on the morning of August 29, the USS Missouri entered Tokyo Bay (Figure 45). Among the crew on board was Electrician's Mate First Class John L Cadman.