Charles Gould Moore

THE FIRST MARINE DIVISION AT CAPE GLOUCESTER & PELELIU

People back home will wonder why you can't forget.

- Eugene B. Sledge, With the Old Breed

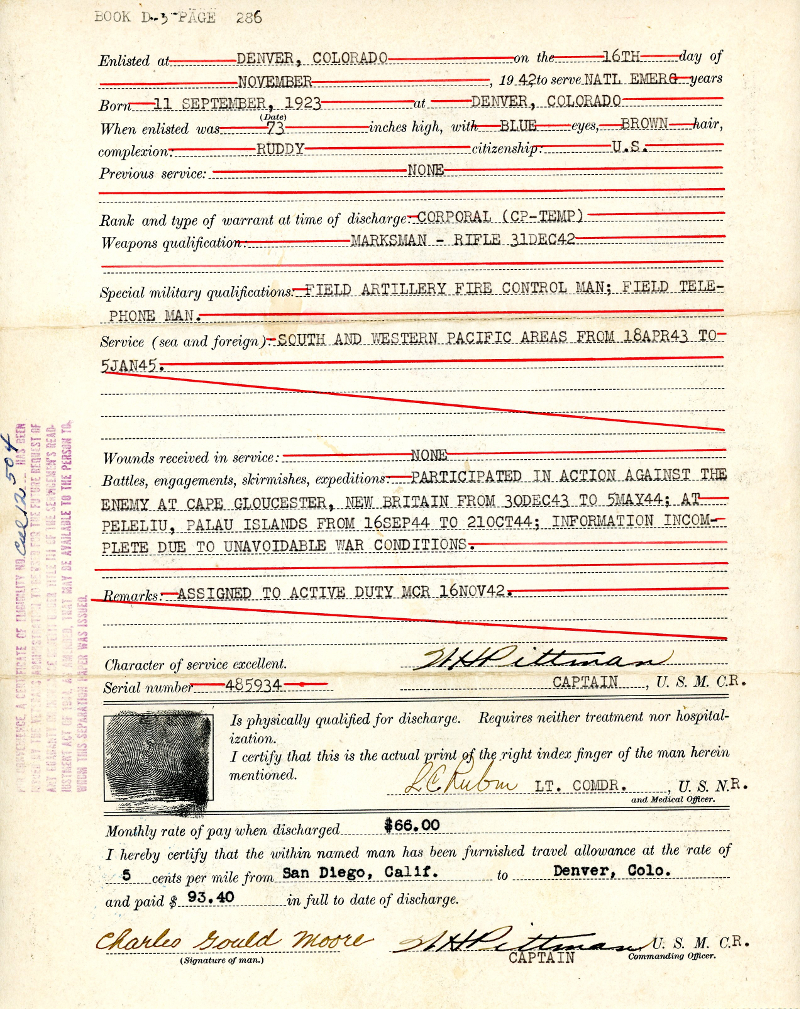

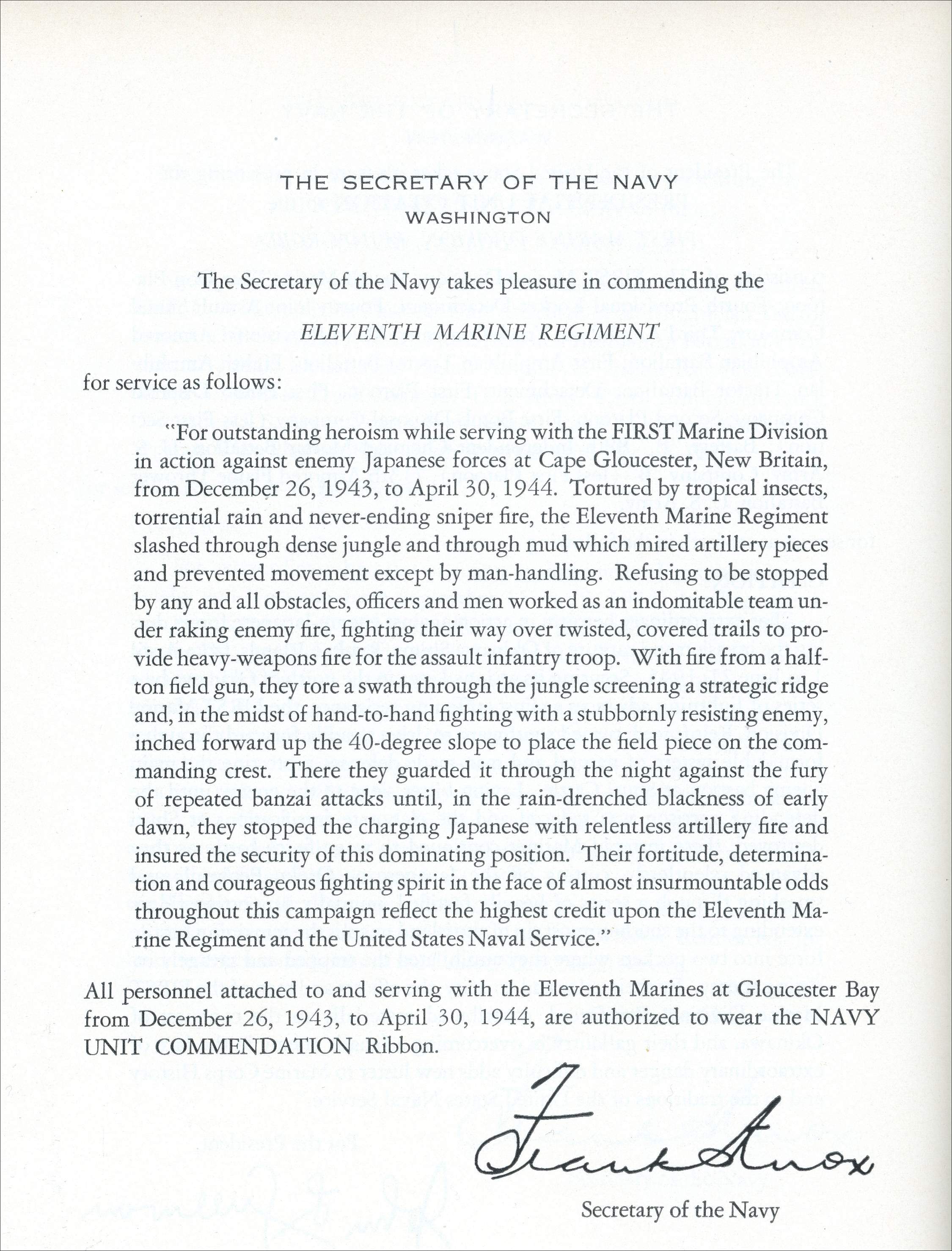

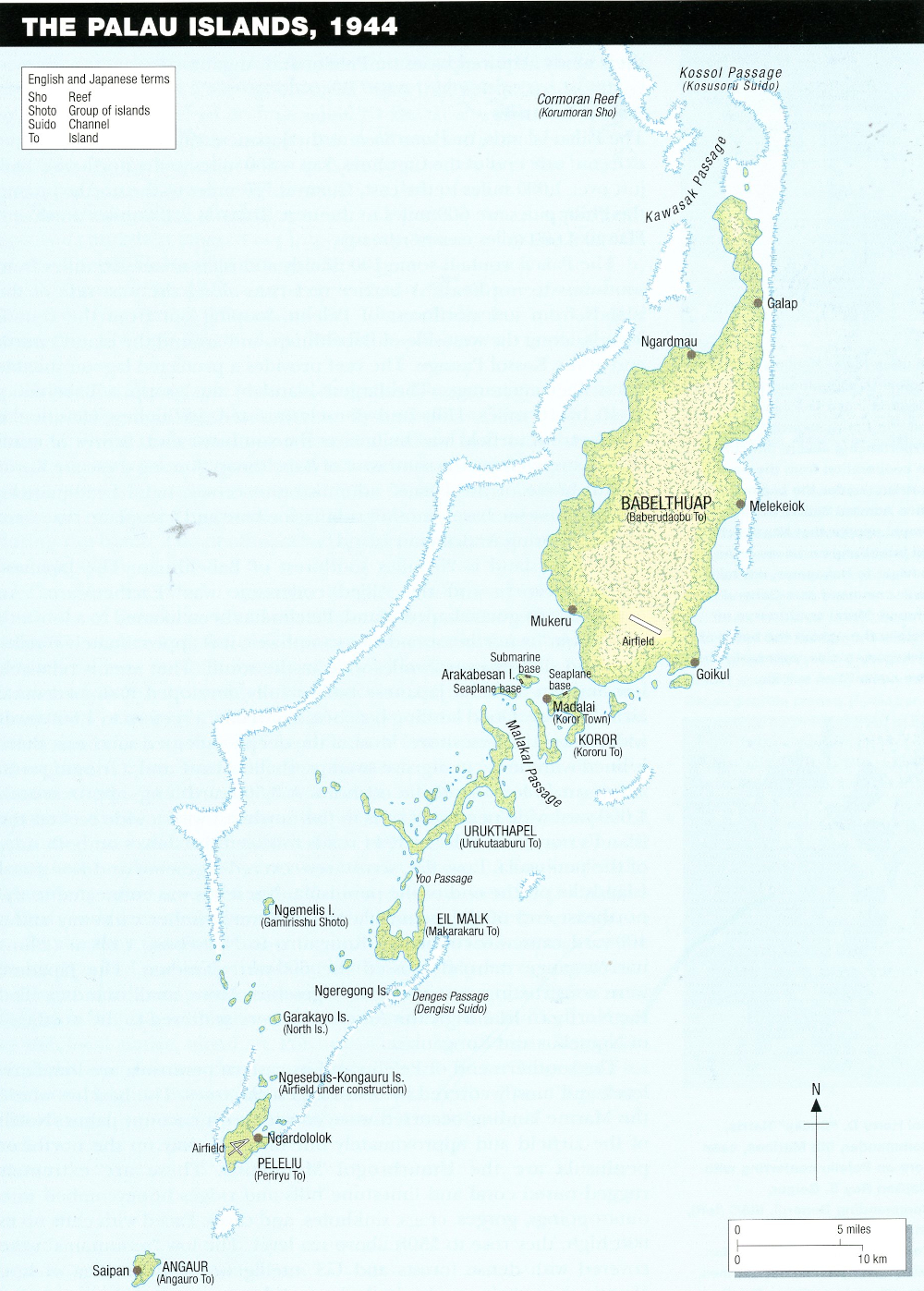

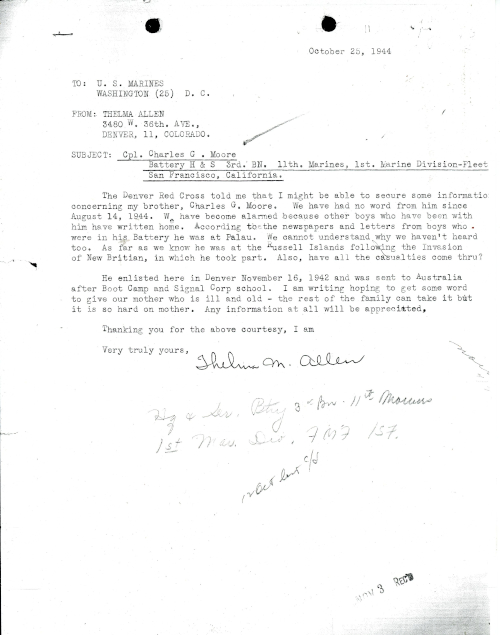

Charles Gould Moore, age 19, my father, enlisted in the US Marine Corps on November 16, 1942 in Denver, Colorado. Upon completion of basic and specialty training, he joined the 11th Marines, 1st Marine Division. While he was with the 11th Marines (an artillery regiment), he participated in major actions against Japanese forces at Cape Gloucester, New Britain, Territory of New Guinea and at Peleliu, Palau Islands as part of the "island-hopping" campaign in the Pacific.

My dad, like many who experienced the chaos and bloodshed of combat in World War II, spoke very little about his experiences in the war. Regretfully, being involved in the normal trials and tribulations of my own life, I never took the time sit down with him and learn more about that period in his life before he passed away in 2001. I knew that he had been attached to the First Marine Division and that he had participated in the Battle of Peleliu. I had done some reading and I knew that Peleliu was considered to be one of the most brutal and bloody battles in the Pacific theater but I knew little about the details of his participation.

Even though I will never be able to hear his personal rendition of the experience, I have tried to fill some of that gap for the purposes of this website by researching and reading sources available in the public domain. I have also obtained his Official Military Personnel File (OMPF) from the National Personnel Records Center in St Louis MO. I highly recommend this source for anyone who wants to learn more about family members who served in World War II.

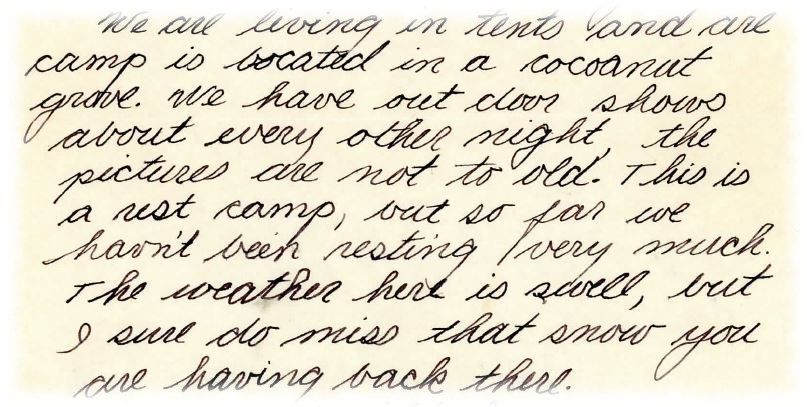

One other significant source of information about my dad's World War II experience is the pictures and documents collected by mom from his time in the Marine Corps. Before she passed away, she served the as de facto genealogist for our family and spent much time and effort compiling albums of the experiences of my dad and two of her brothers during the war. The album she created for my dad can be viewed below.

In keeping with the naming convention I have used for the other World War II (WWII) participants I have documented in this website, from here on down, for the most part, I will refer to my dad as "Chuck", which is the name he went by on an everyday basis.

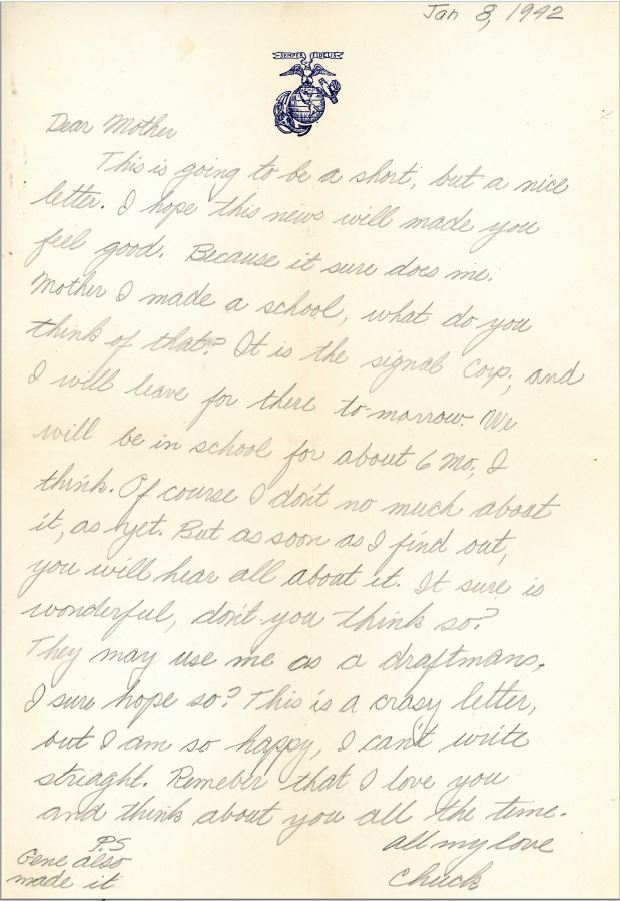

Enlistment in the United States Marine Corps

After Pearl Harbor and upon graduation from high school, Charles Gould Moore felt compelled to serve his country and enlist in the military. He chose the US Marine Corps. The legal age for enlistment was eighteen, but it was common for younger volunteers to lie about their age. Although he was nineteen when he enlisted, he still required a consent form from his parents which in part provided a sworn verification of his birth date (Figure 1).

He was not alone in making this choice, Pearl Harbor motivated thousands of young Americans to join the military:

But first came the new men. All the tenets of discipline, the symbols of an elite corps, would be utterly strange to them. These new men would have to exceed themselves for so quickly taking the title: United States Marine. The NCOs went to work on the new men who would have to be tested even more harshly, to prove themselves worthy of the Corps' first and finest fighting unit.

An officer, who had to do with personnel at the time, says: "They were a strange breed, this bunch that came busting in after Pearl Harbor. Many of them, we discovered, were officer caliber, and could have easily gained that rank if they hadn't volunteered. There's no doubt about it but they wanted to fight. If we resented them at New River ... well, we learned better at the 'Canal."

Source: 'THE OLD BREED: A History of the First Marine Division In World War II'The United States Marine Corps

The history of the Marine Corps goes back a long time. According to folklore, the first Marine was recruited in Philadelphia at Tun Tavern in 1775 under a mandate from the Continental Congress to raise "two battalions of Marines" to serve as landing forces in the Continental Navy. Although the Marines were disbanded in 1783 after American independence was achieved, conflict with Revolutionary France in the following decade led the US Congress to formally establish the US Navy in 1798, and the US Marine Corps as a permanent force under the jurisdiction of the Department of the Navy.

Since their establishment, and up to WWII, the Marines had fought in all US wars, from the Barbary War ("shores of Tripoli"), to the Mexican-American War ("halls of Montezuma"), to World War I and all the wars in between. In most cases the Marines have been first to fight, and they have executed more then 300 amphibious landings on foreign shores since their formal establishment.

Prior to WWII, the greatest expansion of the Marine Corps occurred in World War I (WWI) as a part of the American Expeditionary Force under General Pershing. Total officer and enlisted strength went from 13,725 to 72,400 personnel. Between WWI and WWII many officers envisioned the possibility of a war in the Pacific against Japan. Under Marine Corps Commandant John A. Lejeune, emphasis began to be placed on improvement of amphibious operations needed for such a conflict, including development of better techniques, acquisition of amphibious equipment, and joint exercises with the Army. By 1945, 485,000 personnel were serving in the Regular and Reserve Marine Corps.

The First Marine Division

The 1st Marine Division shoulder patch originally was authorized for wear by members of units who served with or were attached to the Division in the Pacific in World War II; it was the first patch to be approved in that war and specifically commemorated the division's sacrifices and victory in the Battle for Guadalcanal. It features the National Colors - red, white, and blue - in its diamond-shaped blue background with red numeral "1" inscribed with white lettering, "GUADALCANAL." The white stars featured on the night-sky blue background are in the arrangement of the Southern Cross constellation, under which the Guadalcanal fighting took place. Source: MARINES: The Offical Website of the United States Marine Corps

The nickname for the First Marine Division is "The Old Breed". Near as I can tell, the nickname came from an observation made by then 1st LT John W. Thomason, Jr., USMC, after he arrived in France during World War I as a member of the 4th Marine Brigade of the 5th Marines, part of the 2nd Divison, American Expeditionary Forces. After taking stock of his raw new platoon, he later wrote,

"there were also a number of diverse people who ran curiously to type, with drilled shoulders and a bone-deep sunburn, and a tolerant scorn of nearly everything on earth. Their speech was flavored with navy words, and … in easy hours their talk ran from the Tartar Wall beyond Peking to the Southern Islands, down under Manila. … Rifles were high and holy things to them, and they knew five-inch broadside guns. They talked patronizingly of the war, and were concerned about rations. They were the Leathernecks, the Old Timers … the old breed of American regular, regarding the service as home and war as an occupation; and they transmitted their temper and character and view-point to the high-hearted volunteer mass which filled the ranks of the Marine Brigade."

Source: The United States World War One Centennial CommissionThe precursor to the First Marine Division was the 1st Advance Base Brigade. The unit was activated on December 23, 1913 at Philadelphia, Pennsylvania and was re-designated a number of times, finally settling on the 1st Marine Brigade. Between April 1914 and August 1934, elements of the Brigade were deployed to Mexico, Haiti, the Dominican Republic, and Cuba and received campaign credit for service in each nation. The brigade's participation in WWI warranted award of the World War 1 Victory Medal Streamer. In its final form the Brigade was comprised of the 1st and 2nd regiments and, on the cusp of WWII in October 1940, was deployed to Guantanamo Bay, Cuba.

During its existence, and particularly in exercises conducted in the Caribbean in 1940/41, the First Brigade honed the amphibious techniques and equipment that later contributed immensely to the Pacific operations that would be carried out during the oncoming war. Their development and testing of the Higgins landing boat resulted in recommending mass production of the Higgins in the latter part of 1940. By the end of their stay in Guantanamo, they were declared to be "the best amphibious fighters in the world."

The First Marine Division was activated from First Brigade on board the USS Texas on February 1, 1941. There is no record that any ceremony was held and the old hands aboard simply went about their business as before but under a new name.

The FIRST MARINE DIVISION was old before its time.

No use to look in its history for the helplessness of childhood, the misadventures of youth, the respectability of middle age. It was always a crotchety, cantankerous, prideful and intolerant, but wise and fearless, old man.

The First was born with a beard. Like Minerva, an ancient goddess, the First leaped forth from the brain of the Marine Corps "mature and in complete armor" -- mature in the deep folkways of an elite military body, armored with amphibious science its stubborn, aristocratic parent had made a specialty.

Source: 'THE OLD BREED: A History of the First Marine Division In World War II'Initially, the First Division was comprised of three regiments constructed by forming the 5th Marines out of the First Brigade, splitting a portion of the 5th off to form the 7th Marines, and then building the 1st Marines from portions of the 5th and 7th. The ability to do this sort of dividing was enabled by calling up Marine Corps reserves in the fall of 1940. The 11th Marines was added a month later on March 1, 1941.

The 11th Marines

Prior to joining the First Marine Division, the 11th Marines had a history extending back to World War I. The 11th Regiment was an outgrowth of the Mobile Artillery Force and was activated as as artillery regiment on January 3, 1918. At that point in the war, more infantry men were needed in France and, at the request of Headquarters Marine Corps, the Commandant of the Marine Corps granted permission to convert the 11th into an infantry unit. On September 5, 1918, after intensive infantry training in the summer of 1918, the 11th Regiment Joined the 5th Marine Brigade.

By November 2, 1918, the 11th Marine was present and organizing in Tours, France. On November 11, the armistice was signed and the war was over. Having seen no combat, the Marines of the 11th were disbursed throughout France to perform post-war administrative duties. Nine months later, on July 29th, the 11th was headed home embarked on the USS Orizaba. After disembarking at Hampton Roads, Virginia on August 6th, the 11th was deactivated there on August 11th.

The 11th Regiment was once again reactivated in 1927 when unrest in Nicaragua involving US citizens prompted Washington to send in the Marines. The 11th arrived in Nicaragua on May 22, 1927 as part of the 2nd Marine Brigade. The mission of the 2nd Brigade was to help resolve a dispute between the conservative government (backed by the US) and revolutionaries looking to overthrow it. A peace plan between these two entities was agreed to in April, 1927. Called the "Peace of Tipitapa", one of the requirements was that American forces were to stay in Nicaragua to enforce the provisions of the agreement and to supervise subsequent elections.

Enforcement of the Tipitapa agreement proved to be a significant challenge, primarily because the most powerful leader among the revolutionary guerrillas refused to accept its terms. After two years of struggle, including constant jungle patrolling and conflict with the revolutionary forces and sympathetic Nicaraguan peasants, supervision of elections threatened by terrorism, and training of the Guardia Nacional to eventually take over treaty enforcement, conditions in the country were deemed stable enough to begin extracting Marines. In August of 1929, the last of the 11th regiment left Nicaragua and the 11th was deactivated on August 31 en route to Marine Barracks, Quantico.

As with the experience gained by the 1st Advanced Base Brigade, no doubt institutional knowledge was gained by the 11th's experience in Nicaragua that was carried over when the unit was reconstituted as part of the First Marine Division. Of particular note were techniques developed during jungle warfare in opposition to the Nicaraguan revolutionaries. One of the prominent carriers of such information would have been General Alexander Archer Vandegrift who, as a young officer, served in Nicaragua in 1912/13 and would later become the first Division Commander of the First Marine Division at the start of WW II.

After disbanding in 1929, the 11th Regiment disappeared for over a decade. It did not return until, the Marine Corps, living up to its reputation as a force in readiness, began to greatly increase its strength in 1940. On 1 September 1940, the 1st Battalion, 11th Marines, lst Marine Brigade, FMF [Fleet Marine Force] was organized at Marine Barracks, Quantico. On 10 October, 1/11 left Quantico and sailed to Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, arriving there on 21 October. On 1 January 1941, 2/11 was activated at Guantanamo, and, three weeks later, on 23 January, 3/11 was organized there. On 1 February, the 1st Marine Brigade was officially re-designated as the 1st Marine Division, and, on 1 March, Headquarters and Service Battery, 11th Marines, Colonel Pedro A. del Valle commanding, was activated in Cuba. The organization of the 11th Marines was then complete, although two more battalions were added at various times later.

The 11th Marines had now become the artillery regiment of the 1st Marine Division. From 1940 to the present, this has been its role. There were a few scattered instances when units of the 11th were used as infantry for short periods of time, but the 11th was no longer an infantry regiment as it had been in World War I and Nicaragua. At Guantanamo Bay, the 11th began its artillery training, starting with 75mm pack howitzers, which were used by 1/11 throughout the war and by 2/11 for most of the war. The 3d Battalion used 105mm howitzers at Guadalcanal and afterwards.

Source: A Brief History of the 11th MarinesA fourth battalion (105mm howitzer) was added to the 11th on October 22, 1941 at Parris Island. The scattered units of the 11th were all assembled, along with the rest of the 1st Marine Division, at New River, North Carolina in January, 1942 where they underwent combat training until June, 1942. A 5th Battalion (105mm howitzer) was added prior to the 11th mobilizing to San Francisco on June 14. On June 22, the 11th, along with the rest of the First Division departed San Francisco and sailed for Wellington, New Zealand where the First Division would soon receive orders to conduct an amphibious operation against the Japanese at Guadalcanal.

Note: A Brief History of the 11th Marines indicates that a 5th Battalion was added to the 11th Marines prior to June 14, 1942. However, the Command Organization for the Battle of Guadalcanal (August 7, 1942 to February 9, 1943) provided in 'THE OLD BREED: A History of the First Marine Division In World War II' does not list a 5th Battalion for the 11th Marines, but it does list "11th Marines (less 1st,2d,3d, & 4th Btns)" as a Support Group under Col. Pedro A. delValle, the acting Commander of the 11th at Guadalcanal. The Wikipedia entry for Battle of Guadalcanal order of battle does list a 5/11 commanded by Lt. Col. E. Hayden Price. The Wikipedia entry for 3rd Battalion, 11th Marines indicates that 3/11 participated in Guadalcanal but states that the "3rd Battalion 11th Marines was activated 1 May 1943 at Victoria, Australia as the 5th Battalion, 11th Marines, 1st Marine Division, Fleet Marine Force. The Battalion was re-designated 3rd Battalion, 11th Marines on 7 May 1944." The activation date of 1 May 1943 is after Guadalcanal but before Cape Gloucester. The re-designation (from 5/11 to 3/11) is after Cape Gloucester but before Peleliu. So, was there a 5/11 at Guadalcanal? If so, perhaps it is listed in THE OLD BREED as the 11th Marines' Support Group member.

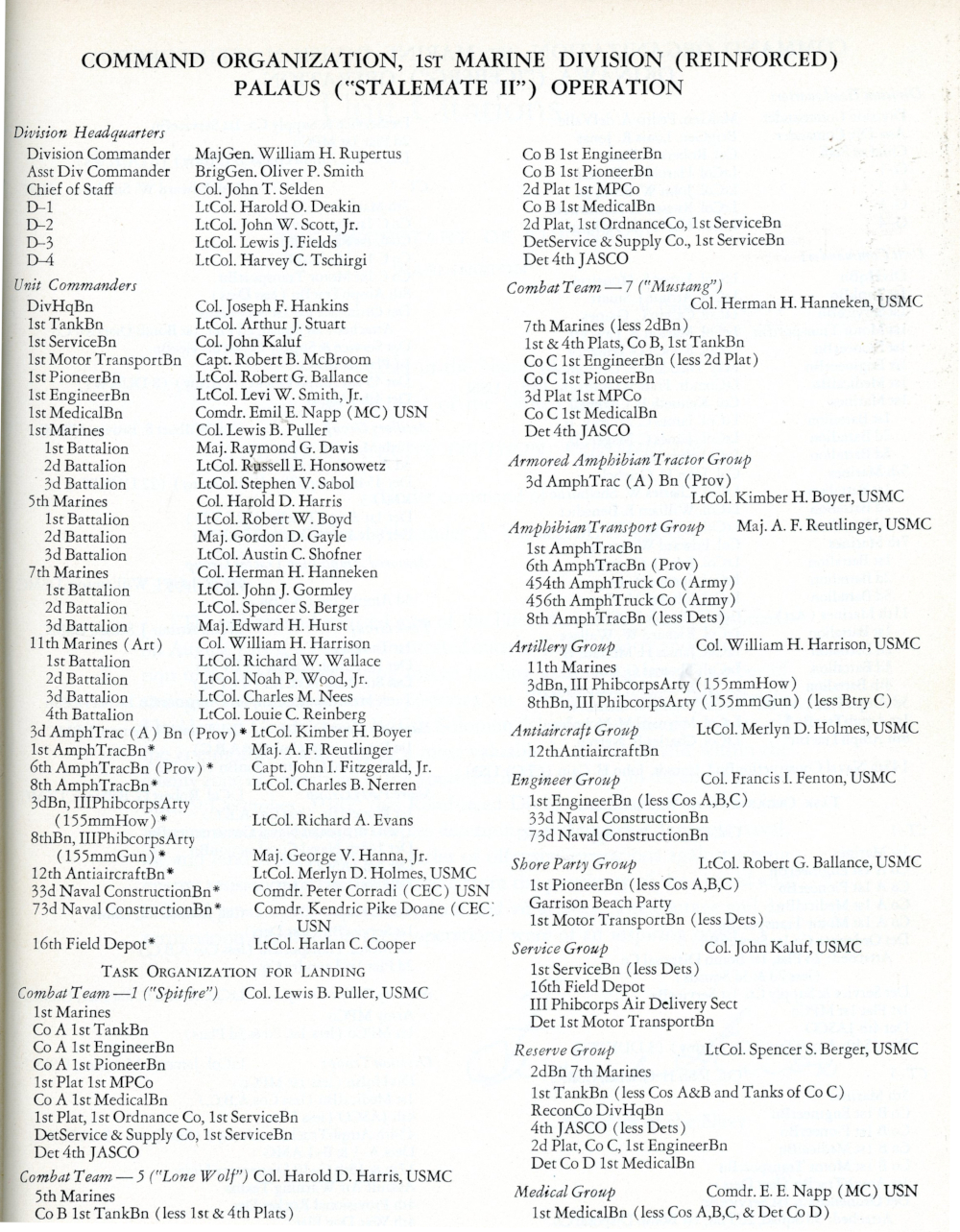

Finally, THE OLD BREED lists a 3/11 and 5/11 for the Cape Gloucester Command Organization, and a 3/11, but no 5/11, for the Peleliu Command Organization. This corresponds to Chuck Moore's personnel record which documents that he joined the 5/11 prior to Cape Gloucester and the 5/11 became the 3/11 after Cape Gloucester and before Peleliu.

Chuck Moore's Job Description With the 11th Marines

In order to best understand the nature of Chuck Moore's participation in the events of the war, it was necessary to have an understanding of what specialty training he received and what his job description was within the unit he served with. The best source of that information proved to be his personnel file (OMPF).

He attended basic training (boot camp) with the 8th Recruit Battalion at the Marine Corps Recruit Depot (MCRD) in San Diego California from November 18, 1942 to January 8, 1943, the standard 7-week period that was in place at that time:

After completing basic training, newly minted Marines were given their forward assignments. Eugene B. Sledge, in his excellent chronicle WITH THE OLD BREED at Peleliu and Okinawa, explained the process as it was for him at the MCRD, on December 25, 1943:

Before dawn the next day, Platoon 984 assembled in the front of the huts for the last time. We shouldered our seabags, slung our rifles, and struggled down to a warehouse where a line of trucks was parked. Corporal Doherty told us that each man was to report to the designated truck as his name was called out. The few men selected to train as specialists (radar technicians, aircraft mechanics, etc.) were to turn in their rifles, bayonets, and cartridge belts.

As the men moved out of the ranks, there were quiet remarks of, "So long, see you, take it easy." We knew that many friendships were ending right there. Doherty called out, "Eugene B. Sledge, 534559, full individual equipment and M1 rifle, infantry, Camp Elliott."

Most of us were infantry and we went to Camp Elliot or Camp Pendleton. As we helped each other aboard the trucks, it never occurred to us why so many were being assigned to infantry. We were destined to take the places of the ever mounting numbers of casualties in the rifle or line companies in the Pacific. We were fated to fight the war first hand. We were cannon fodder.

When Chuck Moore graduated almost exactly one year before Sledge, he was, from Sledge's point of view as expressed in the above quote, one of the lucky ones selected for specialist training and not a member of the infantry "cannon fodder". But as it turned out, both Eugene Sledge (Company K, 3rd Battalion, 5th Marines) and Chuck Moore landed on the beaches at Peleliu on the same day and were exposed to same Japanese "cannon". The difference was that Chuck Moore had to experience Cape Gloucester before Peleliu and Eugene Sledge had to endure Okinawa after Peleliu. (Not to ascribe any special meaning, but I was startled to find out that Eugene Sledge passed away on the same day as my dad, March 3, 2001.)

As the war progressed from December 7, 1941, the growing complexity of the Marine amphibious operations caused the need for additional specialist training to go from acute to chronic. At the beginning of the war the existing selection process for specialty training was inadequate as evidenced by attrition rates of 30 percent or more in many of the specialty classes:

At the outset of the war, the Marine Corps had in effect a selection system based on three criteria: education, previous experience, and aptitude. Of the three, only the first could be measured objectively. A definite level of academic achievement was often stated as a prerequisite for certain courses, e.g., two years of high school, four years of high school, or perhaps two years of college. The candidate might also be required to have completed certain courses, e.g., high school mathematics, physics, etc. There was no objective measurement of the other two requirements.

A man might be required to state that he had been a carpenter or auto mechanic in civilian life, but he was not obliged to prove his ability by any sort of test. Where aptitude was a prerequisite, the judgment of the commanding officers was employed to advantage in cases where students were selected from organized units. A subjective measurement of aptitude for a large number of men just completing recruit training, however, was of little value.

One exception to the general rule was communications training. Written examinations in mathematics, spelling, code, tone perception, and general intelligence were required.

Source: Marine Corps Ground Training in WWIIBy the time Chuck Moore entered basic training, approximately 40 percent of recruits were being designated for further training in formal specialist schools. Starting in October of 1942 a new and improved selection process had been adopted from a scheme that the US Army already had in place. Testing of the new process showed it to be an outstanding success as it cut the average rate of academic failures from 40 to 5 per cent.

Chuck Moore benefited from this process and from the fact that prior to enlisting he had graduated from high school, had taken a number of technical and mathematical courses at Denver University, and was taking engineering courses through the International Correspondence School (ICS). During World War II, ICS was given the War Department contract to develop the department's training manuals.

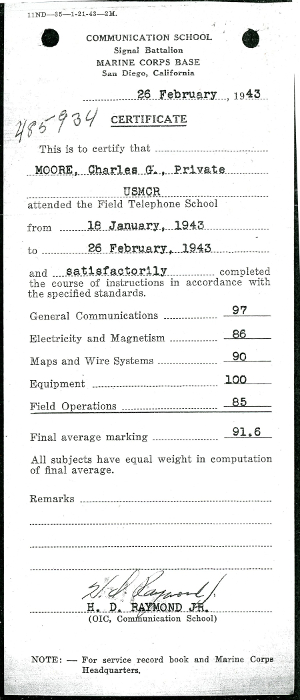

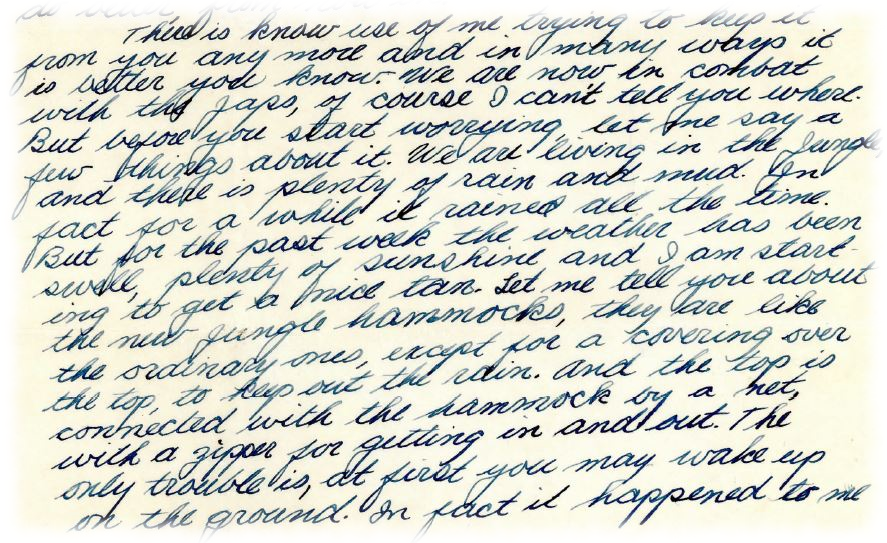

After basic training, Chuck was selected for communication school. The communications training program was conducted by the 2nd Signal Company. Located at San Diego, the company conducted elementary radio operator and field telephone courses. The mission of these schools was to provide personnel for the Fleet Marine Force (FMF) trained in the setting-up, operation, and maintenance of radio and telephone systems in the field.

As expressed in the above letter, Chuck was thrilled about being selected for a school and was certain his parents would be as well, but for different reasons. The extra schooling he received and the correspondence courses he had been taking after high school were aimed at his becoming a draftsman and later an engineer (which indeed happened). So, being selected for a school gave him hope that he might be learning and performing a skill related to that ambition. His parents, on the other hand, were hoping that specialty training would lead to an assignment at an established Marine base rather than in a combat zone. Neither he nor his parents quite got what they were hoping for.

Field telephone men pursued a course of six weeks. This corresponds well with Chuck Moore's service record which indicates that he was assigned to the "Hdqtrs. Co. Signal Bn." on January 7, 1943, reassigned to the "Telephone Co. Signal Bn" on January 16, 1943, and completed his course work (listed in his separation record as "Fld Tel. Lineman and Switchboard 41.1") by February 26, 1943.

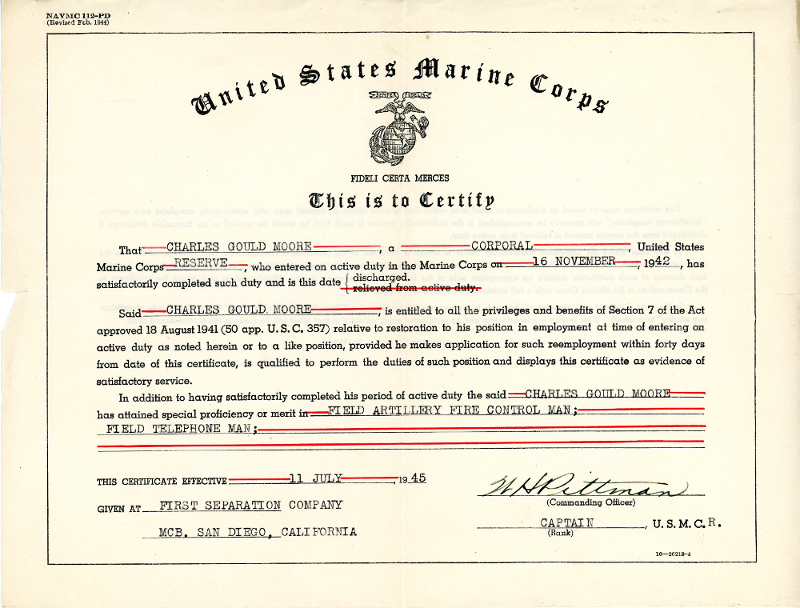

His next assignment was to "Hdqtrs & Service Battery, Artillery Battalion, Training Center, Camp Pendleton, Oceanside, CA" on February 27, 1943. The specific training that he received at the Artillery Battalion Training Center is not indicated, but after about a 6-week period he graduated and joined the "16th Replacement Bn, FMF" on April 5, 1943. Six weeks was the standard length of the USMC fire control specialist course in 1943, although I do not have any paperwork that shows that he graduated from that particular course. His separation papers list his "Principal Military specialty" as "FA. FC. Man 645" and a second specialty as "Fld Tel. Man 641".

I found a listing of War II US Marine Corps occupational specialty codes (MOS code) that describe his principal and secondary MOS's as follows:

645 - FIELD ARTILLERY FIRE CONTROL MAN [FA FC MAN] Performs one or more duties incident to the collection or compilation of field artillery firing data. Operates such instruments as aiming circle, azimuth instrument, battery commander's telescope, one-meter base range finder, field glass, and pocket compass; interprets metro message; uses graphical firing table to assist battery commander in making trigonometric and ballistic calculations to obtain data for the preparation and conduct of artillery fire; performs related fire control duties as required, such as sound or flash ranging observation or survey operations. May supervise a crew in setting up, adjusting, and operating field artillery fire control and survey instruments. Must understand basic principles of field artillery fire control and proper use of field artillery fire control equipment.

641 - TELEPHONE MAN [TP MAN] Performs one or more duties incident to the installation, operation, or maintenance of a wire communication system, such as laying, maintaining, and taking up wire or cable, and installing, maintaining, and operating a portable magneto type of common battery switchboard.

On September 16, 1943, Private Moore submitted a request to change his specialty "from Private First Class, Communications Warrant, to that of Private First Class, temporary appointment, line duty, U.S. Marine Corps Reserve. The reason for this request is that I desire duty with the Artillery Instrument Section." He cited his civilian engineering education and experience as qualifications for such a change and noted that, "I have no experience in Communications." At this point in time, he had no actual combat experience to serve as a basis on which to compare the two specialties. My take on this request is that it was primarily motivated by his desire to perform in a specialty more closely aligned with his intent to become an engineer after the war. The request was disapproved "in view of the shortage of personnel with like [TP] qualifications."

Note regarding the wording of this request: 1) As a member of a Fleet Marine Force, "line duty" refers to the status that "all Marines are of the line, thus, all marines are capable of performing line duties, whether infantry or other contributions to the Marine air ground task force, the premier USMC war fighting organization." This is relevant to Chuck Moore's experience in that members of artillery units were often commandeered to perform infantry duties when needed. This was the case at Peleliu in situations when tight terrain often favored the individual Marine with a rifle over artillery in countering Japanese troops entrenched in caves and underground bunkers, and 2) "Marine Corps Reserve" in the context of World War II refers to the thousands of mostly volunteers that were necessary to augment the Regulars in order to accomplish the mission:

As the situations escalated in Europe and the Pacific, the Marine Corps Reserve rapidly expanded in 1940 over a year prior to the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. Massive manpower was required to execute the newly developed amphibious warfare doctrine. The Pacific island-hopping campaign involved a surge of Reserve Marines into the Regular forces. The Marine Corps expanded from approximately 15,000 Regular Duty personnel to more than 485,000 Marines by 1945, with Reserve Marines constituting the bulk of personnel strength. Of the 589,852 Marines to serve during World War II, approximately 70 percent were Reserves. One general officer described the Reserve as "... a shot in the arm when war came."

Source: MARINES: Marine Corps Forces ReserveIn June of 1944, after Cape Gloucester and prior to Peleliu, Corporal Moore submitted another request to change his specialty from "Communication Personnel" to "Line Duty .. in the Fire Control Center of an Artillery Battalion". In the request he noted that "Since joining this Battalion, ... under permission of the Division Commanding General I have been given specialized instruction in artillery fire direction." I do not have any specific documentation indicating that this request was granted, however, Corporal Moore's separation papers, as alluded to above, in addition to his Separation Certificate and his Honorable Discharge, stated that at the time of his discharge his primary MOS was Field Artillery Fire Control Man.

So - getting back to the question of Chuck Moore's WWII combat job description - his assignment while deployed in combat was with the 5th Battalion, 11th Marines, First Marine Division, later re-designated as the 3rd Battalion, 11th Marines, First Marine Division after Cape Gloucester and before Peleliu. The 5/11 and 3/11 were, and 3/11 still is, an artillery battalion/regiment (105 howitzers during WWII). Given his specialty training, the nature and timing of his second request to change his MOS, and the indication in his service record that his principal MOS at separation was 645, it is very likely that he initially served as a Field Telephone Man at Cape Gloucester. However, as alluded to above in his request to change his specialty, he may very well have effectively transitioned to the Field Artillery Fire Control Man MOS while at Cape Gloucester, and later served in that role at Peleliu.

Preparation For War

Although relatively small, at the time of formation, the First Marine Division was the first integrated amphibious strike force of its size in the US armed forces. The assembled force proved to be too big for accommodation at the First Brigade's home at Quantico, Virginia so part of the division was split off to Parris Island, South Carolina. Before the men could make themselves at home, they were put aboard ship and transported for maneuvers to a 100,000-acre-plus swampland the Marines had acquired off New River, North Carolina. There they conducted exercises through June, July, and August of 1941, culminating in a Joint Force exercise that was the largest of its kind ever held in the US.

During their time at New River, which never really ended until they were deployed overseas, the men lived in "Tent City" (later to be replaced by the buildings of Camp Lejeune), constructed by the men themselves from whatever materials they could muster. With the exception of the bitter cold experienced during the winter of 1941/42, the crude living conditions and swampy, bug-invested environment proved to be emblematic of the conditions they would later experience in the Pacific campaign. Afterward, one staff officer related a statement he made while at New River: "Why this division, training here, won't be fit for a thing but jungle warfare." He added, "It's surprising how much like Guadalcanal that damned place was."

Guadalcanal

command tent, Guadalcanal, 1942.

On May 1, 1942, the advanced echelon of the First Marine Division boarded trains at New River and headed for Norfolk, Virginia from where they would embark aboard transport ships headed for Wellington, New Zealand. They arrived in Wellington on June 20, expecting to undergo further training to benefit the hundreds of new recruits the Division had acquired, average age less than 19 years. Instead, six days after they arrived, they learned about a place called Guadalcanal (gwahd-l-kuh-nal) when the Division Commander, General Alexander Archer Vandegrift, was handed a dispatch from the Joint Chiefs of Staff that read: "Occupy and defend Tulagi and adjacent positions (Guadalcanal and Florida Islands and Santa Cruz Islands) in order to deny these areas to the enemy and to provide United States bases in preparation for further offensive action." At that point in time, the First Marine Division was just about the only ready striking force the nation possessed and so, naturally, they were given the assignment.

They were given a D-Day date of August 1st:

That was thirty-seven days away and, considering that the second echelon would not arrive until July 11, the Division had a little less than a month to unload and to re-load, combat-style.

The margin was slimmer than that, at least as it appears in a staff problem used in the post-war curriculum on the Marine Corps Schools. "The concentration," begins the problem, "is to take place in the Fijis, six days from New Zealand by transport. That leaves 31 days. Koro, in the Fijis, is seven days from the objective. That leaves 24 days in which to reconnoiter the objective, get information, study the terrain, make a decision, issue orders, load 31 transports and cargo carriers, embark 20,000 men and 60 days' supply, effect a rendezvous with supporting naval forces and, in addition, conduct a thorough set of joint rehearsal exercises ..."

"Division headquarters and one combat team has just arrived at Wellington," continues the problem. "The second combat team, the First Marines, is at San Francisco, the third combat team, the Second Marines, is at San Diego, the First Raider Battalion is in New Caledonia, the Third Defense Battalion is at Pearl Harbor, along with supporting naval forces."

Source: 'THE OLD BREED: A History of the First Marine Division In World War II'After further consideration of the amount of preparation needed by both the Marines and the Navy support group, D-Day was moved back to August 7, 1942. All overnight leave was canceled on June 30 and the Marines were organized into around-the-clock working groups. Arriving transports had to be unloaded and then reloaded in combat configuration, sometimes simultaneously. To gain time and space, one-third of the planned-for supplies had to be left behind.

After completing preparations, the First Division departed Wellington and arrived at Koro Island, in Fijis in late July, where pre-invasion practice for landing operations would be conducted and Task Force 62 would be assembled.

The convoy left Koro and arrived at Guadalcanal on August 6th. The convoy included three carriers (Saratoga, Enterprise, and Wasp), one battleship (North Carolina), some cruisers, and a number of destroyers along with the transports carrying the First Division. The convoy represented nearly all of the effective striking force of the US Navy at that time.

Since my dad did not join the First Marine Division until after Guadalcanal, my intention here is to address the battle in the context of the follow-on campaigns that Chuck Moore was a part of. There are many sources of information (books, movies, USMC documents, videos, web sites, etc.) that can provide the interested reader with more in-depth information about Guadalcanal. Wikipedia is not always the best source, but the article Guadalcanal Campaign is a well done comprehensive summary of the battle and provides an exhaustive listing of other references with more detailed information. The following video (Figure 9) is from the production of the HBO Miniseries, The Pacific. It contains a mix of actual footage, dramatizations, and interviews with Guadalcanal veterans. It is a good ten-minute summary of what happened at Guadalcanal.

The Battle of Guadalcanal was the first major Allied ground offensive carried out against against the Japanese. As alluded to in the video, it exposed the myth of Japanese soldier invincibility and provided insight into how the Japanese forces would defend their occupied territories in the Pacific. The First Marine Division gained a clearer picture of what was needed to successfully conduct combat operations in the tropical climate and jungle environments of the Pacific islands. It marked the transition from defensive to offensive Allied operations which would be carried forward with the island-hopping strategy that would eventually lead to the defeat and surrender of the Empire of Japan.

The victory at Guadalcanal also provided a needed emotional uplift for the American public:

The fact that Guadalcanal was the first offensive strike might not have impressed the public so much had not the Japs in the months before made Americans look like such easy marks. There was the humiliation of Pearl harbor, a nasty and deep cut in national pride; there was our helplessness to aid the men of Corregidor, Marines as well as Army troops; there was, altogether, our impotence before consistent and relentless Japanese advance throughout the Pacific.

True, the Navy turned back the Japanese at Coral Sea and Midway. But that, somehow, did not capture the imagination nor satisfy the national need, not so much for revenge, as for proof that our men were as good fighters, had as much moral stamina as theirs. "People had come to believe," an officer recalls, "that the Japs were supermen, that maybe our American boys really weren't as rugged as the Japs. What people wanted, back in the summer of '42, was a hand-to-hand battle royal between some Japs and some Americans to see who would really win."

That exactly is what happened on Guadalcanal. The Japs and the men of the First Division came out of the thick jungle at one another day after day for four months, meeting in hand-to-hand combat, grappling with knives and bayonets, and firing at one another with the small arms of the individual foot soldier, the issue always in shaky balance.

But when this intimate campaign was over, the men of the First Division had proved to the satisfaction of themselves, their officers, and the American public that the youth of democracy can meet and defeat the youth of a nation regimented in fanaticism.

"There was a national sigh of relief when the Japs were knocked off that island," a radio news commentator has said, and the name Guadalcanal has passed into history bearing the magical qualities of such other American battlefields as Valley Forge, Gettysburg and Belleau Wood.

Source: 'THE OLD BREED: A History of the First Marine Division In World War II'Chuck Moore was not at Guadalcanal. He joined the 11th Marines, First Marine Division three months later in Melbourne, Australia.

After completion of basic and specialty training in San Diego:

- 4/5/43 – joined 16th Replacement Battalion, FMF (Fleet Marine Forces)

- 4/17/44 – Embarked on board USS Lurline at San Diego, California en route to Melbourne, Australia

- 4/24/43 – crossed the equator for the first time

- 5/6/43 – joined Headquarters Co. 7th Replacement Battalion, FMF (apparently while still on board Lurline in port at Melbourne)

- 5/10/43 - disembarked USS Lurline at Melbourne, Australia

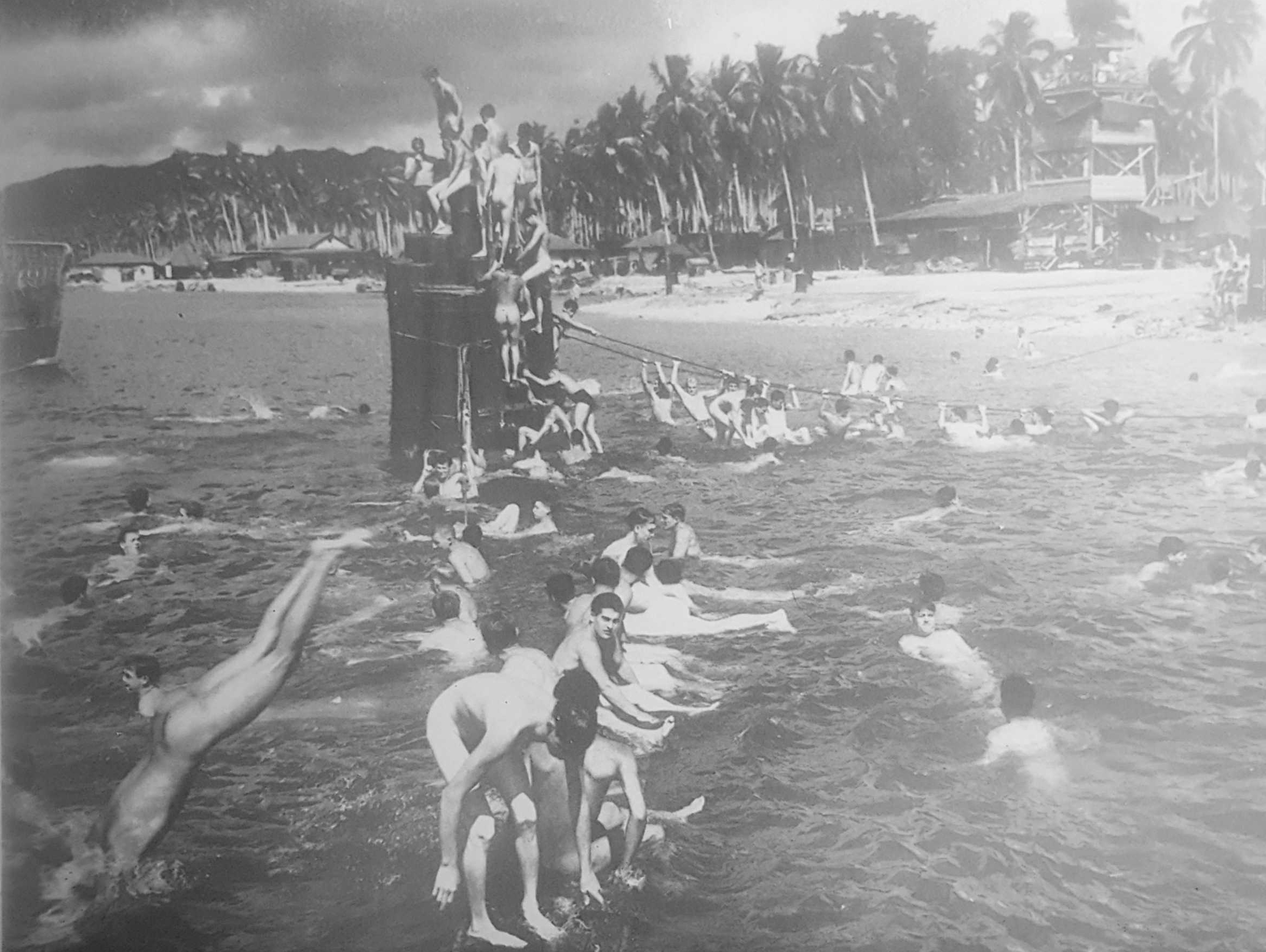

When Chuck Moore arrived at Melbourne, the First Marines were there resting, recuperating, and training after Guadalcanal. As a brand new recruit, I'm sure he got an earful from the veterans who survived the battle. Less than six months later, Private 1st Class Chuck Moore and the rest of the new recruits would join the veterans in embarking on a voyage to the First Marine Division's next island campaign at a place called Cape Gloucester.

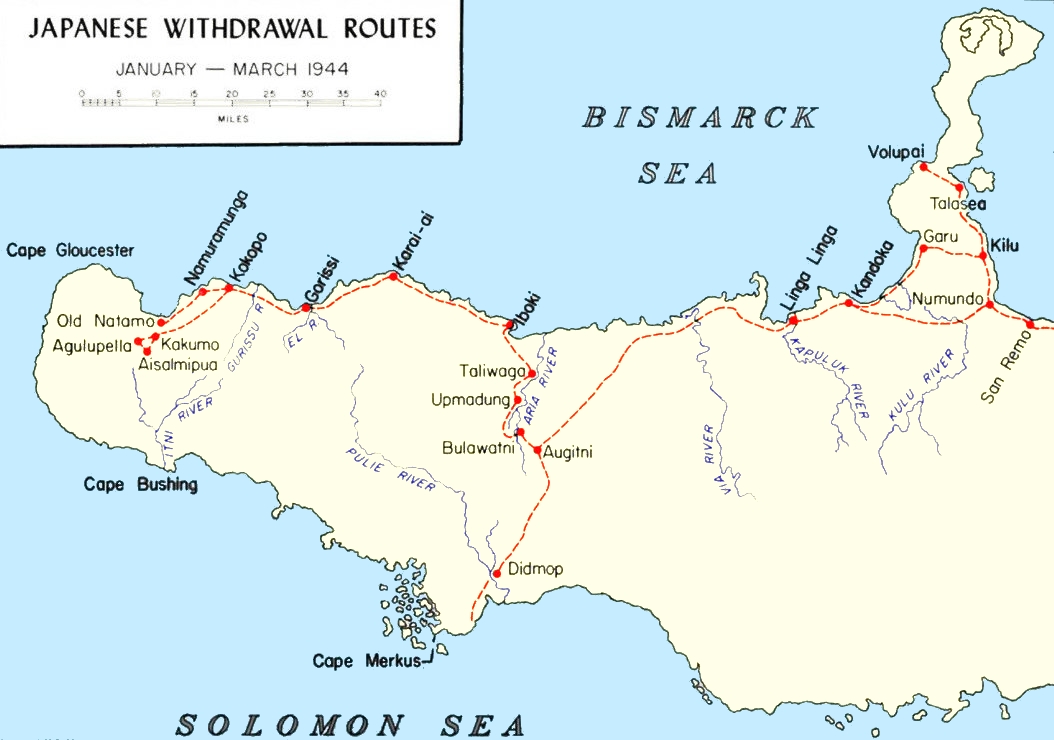

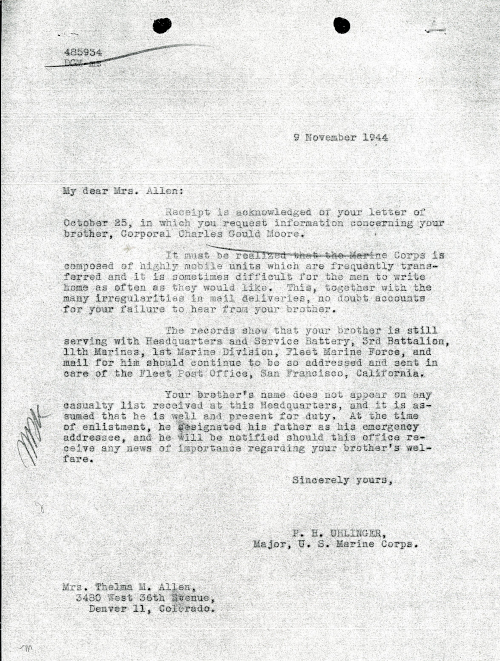

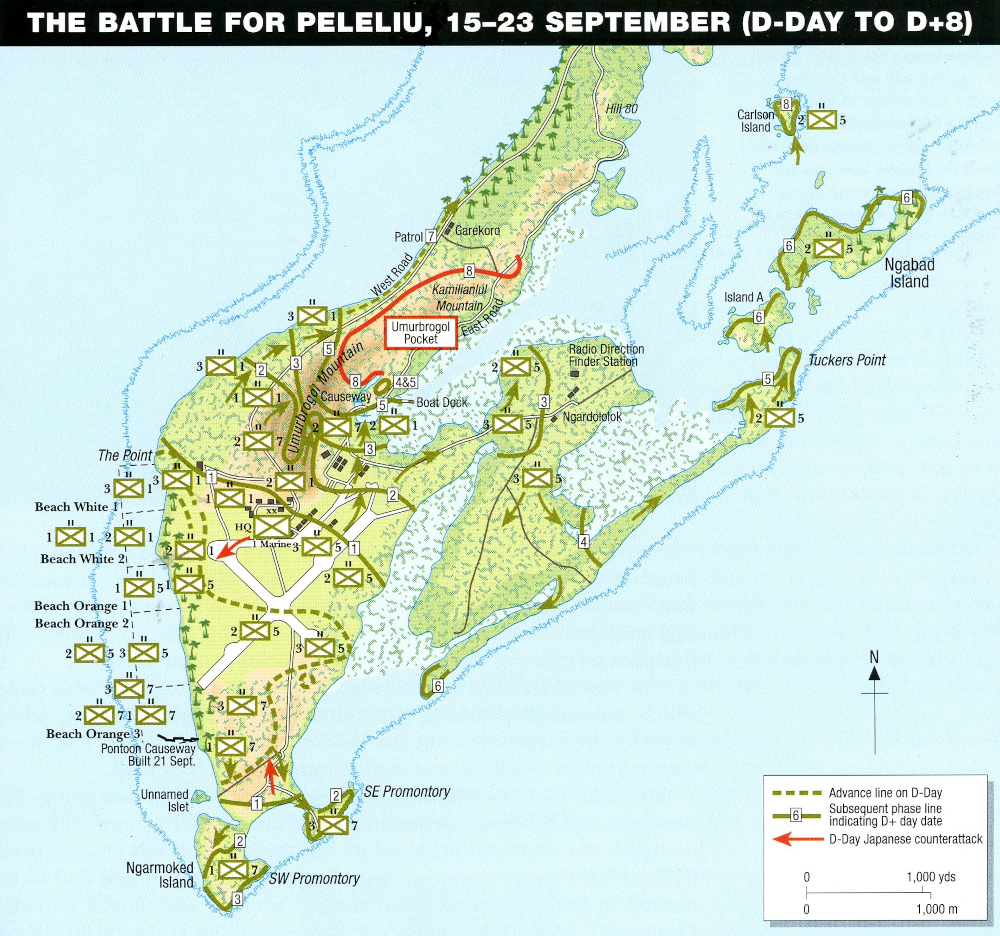

Cape Gloucester

Cape Gloucester (GLAW-ster, GLAW rhymes with CLAW) is located on the western tip of the island of New Britain (Figure 11). At the outset of the Pacific war, New Britain was a territory of Australia. In 1942, Japan attacked and occupied New Britain with thousands of troops and set up a major air base at Rabaul and two small airstrips inland from Cape Gloucester (in addition to numerous other military facilities throughout the island). By late 1943, the Allies were gaining the upper hand and Australian army divisions were advancing north along the coast of New Guinea. The landing at Cape Gloucester was designed to preclude any air attacks on Australian forces originating from the airstrips, to establish a allied base from which to provide air support to the Australian advance, to disrupt ongoing Japanese barge traffic between the Cape Gloucester area and Rabaul, and to ensure free Allied passage through the straits of Vitiaz and Dampier which separate New Britain and New Guinea.

The Gloucester action was conducted under the command of the US Army led by the Supreme Allied Commander of the South West Pacific Area, General Douglas MacArthur. The action was under the auspices of Operation Cartwheel within a subordinate operation specific to the invasion of New Britain, codenamed Operation Dexterity. The overall objective of Cartwheel was to isolate and harass the Japanese base at Rabaul (and avoid the need to assault the large garrison there head-on), and sever the Japanese lines of communication throughout the Southwest Pacific area. The Gloucester landing was planned and executed under yet another codename, Operation Backhander.

MacArthur's Sixth Army was designated to plan and execute Operation Backhander. During the planning process, one of the initial concerns was getting bogged down against the large jungle-wise Japanese force garrisoned on New Britain. They needed a jungle-wise force of their own. Fortunately for the planners, the First Marine Division was already included in the Sixth Army's organizational structure and at that time the First was ensconced in Melbourne, Australia, resting and recuperating from an extensive jungle engagement at Guadalcanal.

In July 1943, the First received the initial directive for the Cape Gloucester campaign and soon thereafter obtained the Sixth Army plan. Division was not happy with that plan. It was considered too complicated and called for a dangerous dispersal of forces landing at several widely spread points rather than the Division's preference for force concentration at the objective. Before points of contention could be ameliorated between the Sixth Army and the First staffs, the Division was given orders to mobilize from Melbourne to Goodenough Island and New Guinea.

5th Battalion/11th Marines Private 1st Class Chuck Moore had arrived at Melbourne to join the First Marine Division on May 10, 1943. On that date he was assigned to "Battery 'P', H&S Battery, 5th Battalion, 11th Marines, FMF". Twenty-one days later, on May 31, his assignment changed to "H&S Battery, 5th Battalion, 11th Marines, 1st Marine Division, FMF". Here is a definition of a Marine Corps H&S Battery:

In keeping with the long-standing practice of referring to company sized artillery units as "batteries" the headquarters company equivalent element of an artillery battalion or regiment, or a low altitude air defense battalion, is referred to as a Headquarters Battery (Field Artillery) or a Headquarters and Service Battery (-) (LAAD) / Headquarters and Service Battery Detachment.

Each Marine artillery battalion has a 199-member battalion headquarters battery that contains the battalion headquarters, an operations platoon, a service platoon, a communications platoon, and the battery headquarters (T/O 1142G). A Marine artillery regiment has a 380-member regimental headquarters battery consisting of the regimental headquarters, an operations platoon, a communications platoon, the battery headquarters, an artillery electronic maintenance section, an engineer equipment platoon, a motor transport section, and a counter battery radar platoon (T/O 1101H).

Source: Wikipedia: Headquarters and Service CompanyMy interpretation of this definition is that Chuck Moore was initially assigned to the H&S component of an individual artillery battery, Battery "P", within the 5th Battalion, and then re-assigned to the battalion-level H&S component of the 5th Battalion, 11th Marines (5/11). That is, his assignment went from H&S battery level to H&S battalion level. As described above, as best as I can determine his MOS prior to Cape Gloucester was 641 - Telephone Man (i.e., communications), so it seems likely that he performed at Gloucester as a member of the 5th Battalion H&S, 11th Marines' communications platoon.

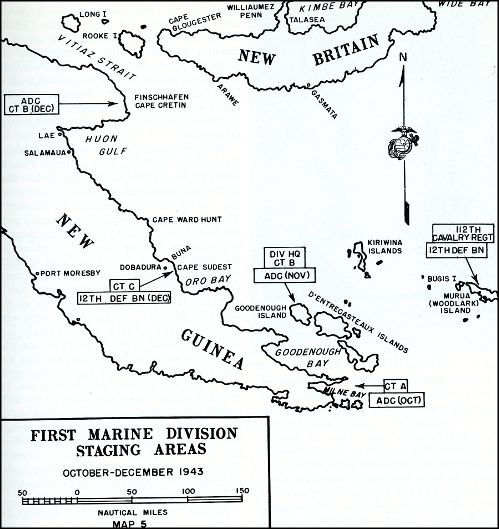

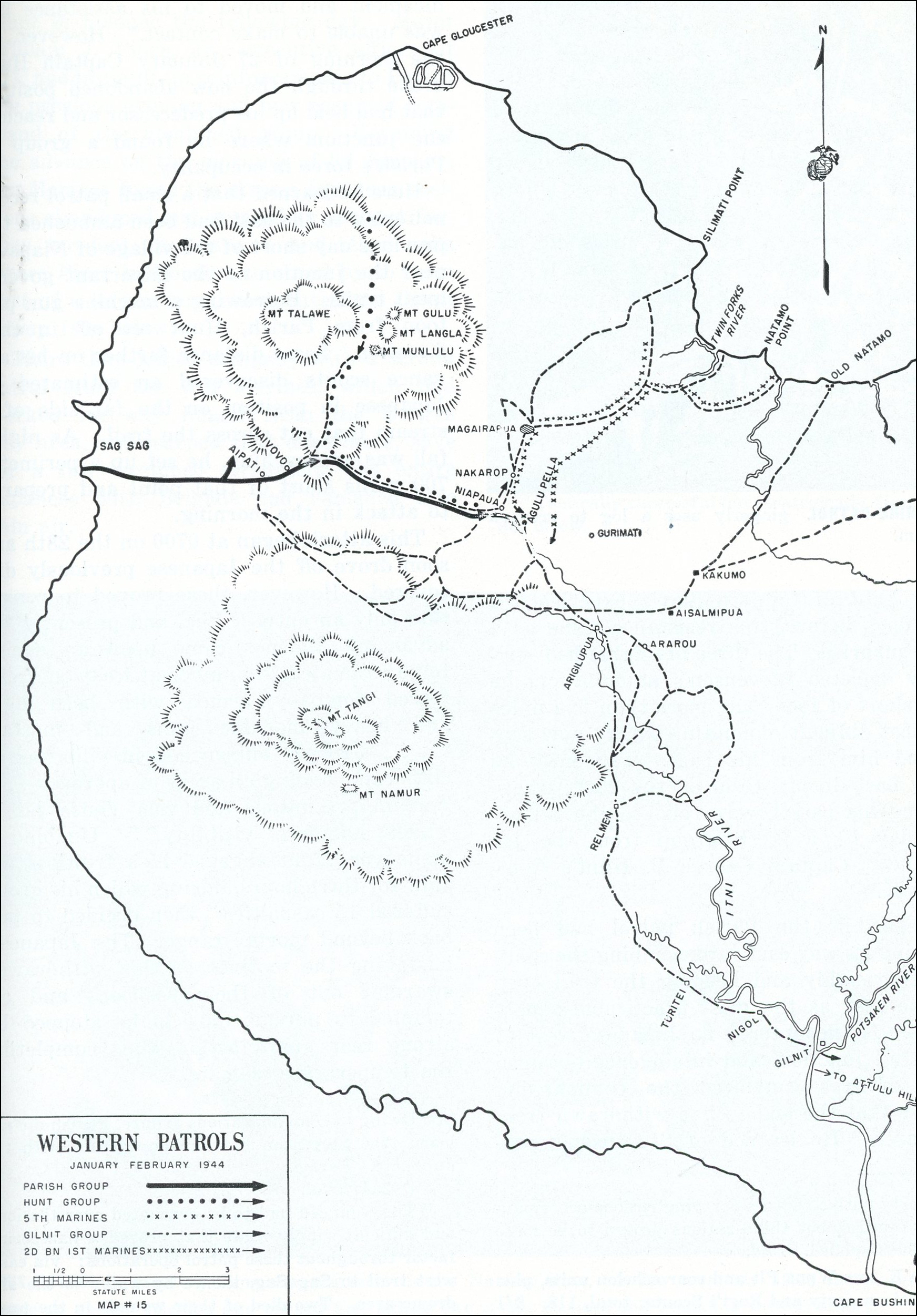

Upon arriving in the New Guinea theater, elements of the Division were to be staged at a number of different locations: the 5th Marines to Milne Bay, the 7th Marines to Oro Bay, and the 1st Marines, Engineer regimental headquarters, and Division headquarters to Goodenough Island. All of these locations had been previously secured by Australian-led Allied victories over Japanese forces in 1942 and early 1943. These locations are shown on Figure 11.

On September 26, 1943, Private 1st Class Charles G Moore's service record indicates that he had "embarked on board the Liberty Ship USS James W Grimes at Melbourne, Victoria, Australia and arrived at Milne Bay, New Guinea" on October 18, 1943; assembling there, in concert with the 5th Marines, as part of the 5th Battalion, 11th Marines. While at Milne Bay, Private Moore was promoted to Corporal Moore, Communications Specialist on December 1, 1943.

By October 23, all elements of the First Marine Division that would participate in the Cape Gloucester campaign had left Melbourne and were at, or in transit to, their designated locations. Once assembled in the New Guinea operations area, they underwent training to, among other things, learn about a new fleet of small ships and boats that were ideally suited for the eventual mobilization from New Guinea to Cape Gloucester. Three days prior to final embarkation from the staging areas, all the craft that would take part in the assault, including the new LSTs (Landing Ship, Tank), LCIs (Landing Craft, Infantry), and LCTs (Landing Craft, Tank), would take part in a rehearsal landing at Cape Sudest (Oro Bay).

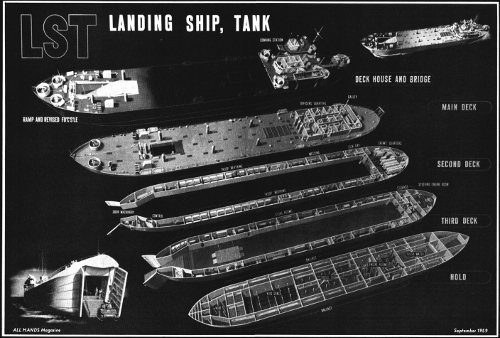

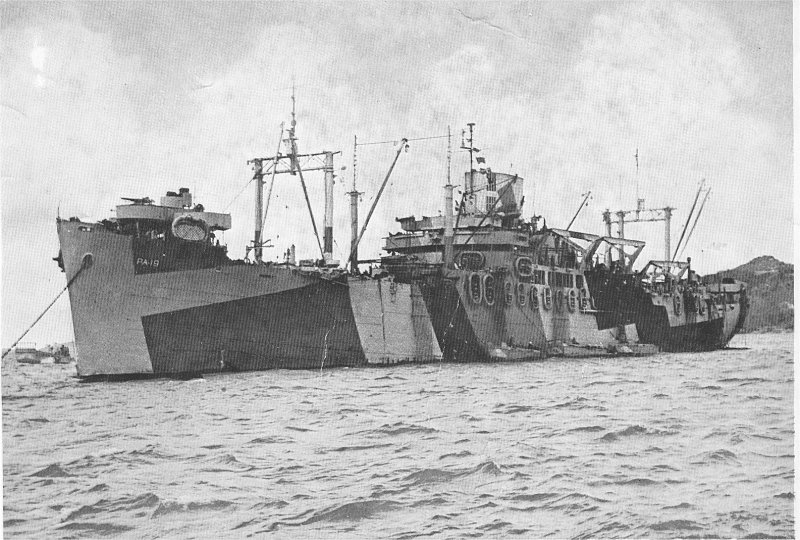

Note: Of particular importance were the LSTs which could transport not only tanks, but all sorts of other military vehicles as well as over 200 troops. They were designed with a special flat keel that allowed them to land on the beach with no need for docks or piers, and were equipped with large bay doors and a ramp in the bow so that vehicles could be driven directly onto the beach. Figure 14 illustrates how the LSTs were configured.

In late November, General MacArthur visited Goodenough to review the Cape Gloucester operations plan. During that review, First Division headquarters staff expressed their dislike for the existing Sixth Army plan. After further discussions between the Sixth Army commander, Lieutenant General Walter Krueger, First Marine Division commander General William H. Rupertus, and their respective staffs, a revised plan that was more in-line with Marine Corps philosophy was approved. Division staff member Lieutenant Colonel E A Pollack, later explained that, "This plan was most acceptable. It kept the Division intact, and permitted the landing of a sizable force against an enemy known to be superior, and well established. This was in keeping with the views of the Division of initially placing an overwhelming force on the beach ..."

The US troops were opposed by elements of the Japanese 17th Division (Lieutenant General Yasushi Sakai), which had previously served in China before arriving on New Britain in October and November 1943. These troops were known as "Matsuda Force", after their commander, Major General Iwao Matsuda and consisted of the 65th Brigade, with the 53rd and 141st Infantry Regiments and elements of the 4th Shipping Group. These troops were supported by field and anti-aircraft artillery, and a variety of supporting elements including engineers and signals troops. Just prior to the battle, there were 3,883 troops in the vicinity of Cape Gloucester.

Source: Wikipedia: Battle of Cape GloucesterNote: The entire Matsuda Force garrison was estimated to be 10,500 men scattered throughout a wide area on New Britain.

Documented information and maps for western New Britain were almost non-existent for planning purposes. Available off-shore charts and surveyed mapping dated to the German occupation in the early 1900's. Intelligence officers supplemented these by interviewing anyone they could identify who had ever lived on or otherwise had knowledge of the island. In the end, maps were developed primarily from extensive photographic surveys done by the Allied Air Forces. The surveys, however, were hampered by the dense jungle environment and Japanese camouflage efforts. To provide some ground-truth to the planning maps, a program of amphibious reconnaissance was implemented by clandestine patrols using PT boats and rubber rafts to land ashore and scout the terrain. These missions were conducted at great risk by a group known as the Alamo Scouts comprised of men from the US Army, Navy, and Marine Corps, and the Australian Navy.

Note from The Campaign on New Britain: To facilitate prisoner interrogation, Sixth Army loaned the division 10 enlisted men, all Nisei (American-born Japanese). The accommodation was accepted somewhat reluctantly by the Marines who feared for the safety of any Japanese under combat conditions, regardless of citizenship or uniform. Plans called for the Nisei to handle translations while eight officer-interpreters questioned prisoners. Despite the original hesitancy, relations between the Marines and the Nisei were friendly and improved with time. The soldiers proved of inestimable value in the D-2 section and won the following accolade:

For Operation Backhander, the First Marine landing forces were divided into three combat teams: 1) Combat Team A, "Reserve Group" included the 5th Marines and Corporal Moore's 5th Battalion/11th Marines, 2) Combat Team B, "Wild Duck Group" including 1st Marines, and 2nd Battalion/11th Marines, "Stoneface (Landing Team 21 - LT21) Group" including 2nd Battalion/1st Marines, Battery H/3rd Battalion/11th Marines, "Antiaircraft Group", and "Engineer Group", and 3) Combat Team C, "Greyhound Group" including 7th Marines, 1st Battalion/11th Marines, and 4th Battalion/11th Marines. The Combat Team assignments appear to me to be primarily a way of grouping a given set of units according to their destinations/assignments and assigning a specified set of ships to them within the convoy. A detailed listing of the Command Organization for Cape Gloucester is provided in 'THE OLD BREED: A History of the First Marine Division In World War II'

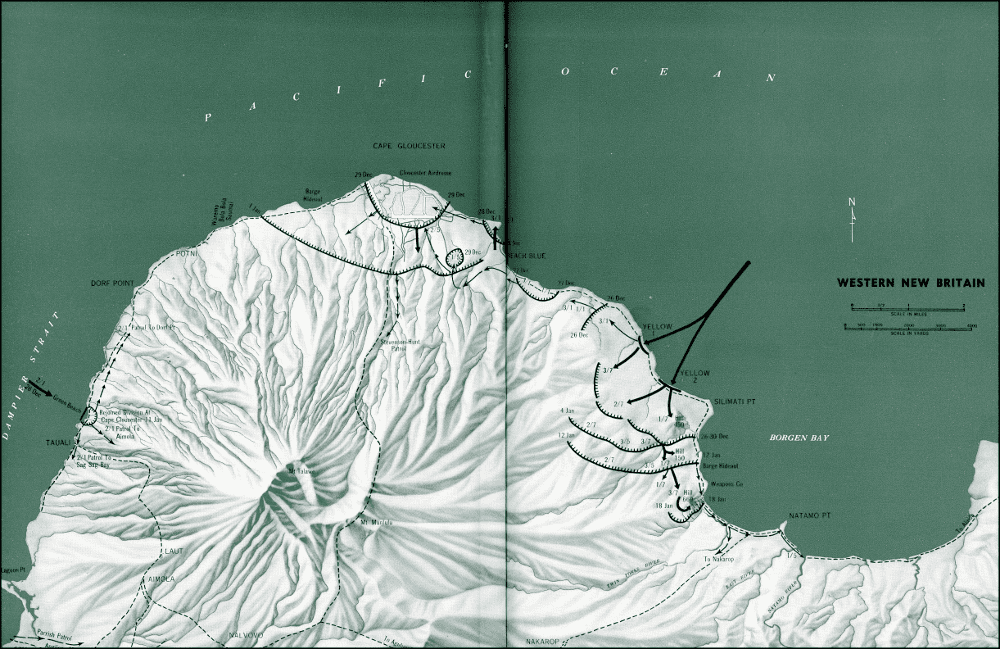

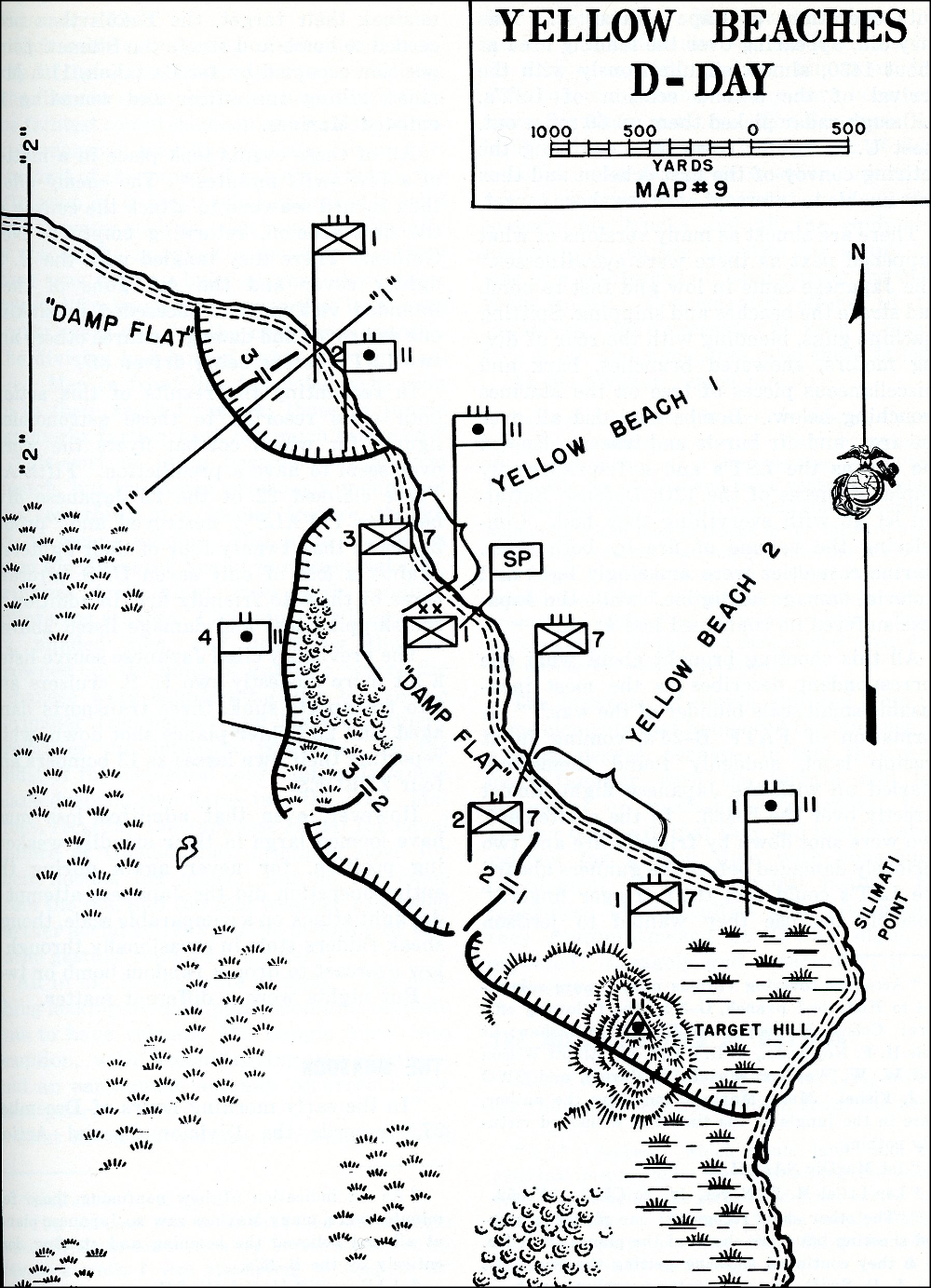

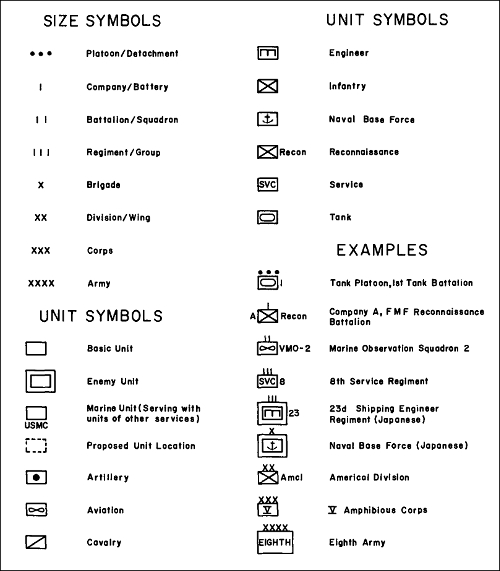

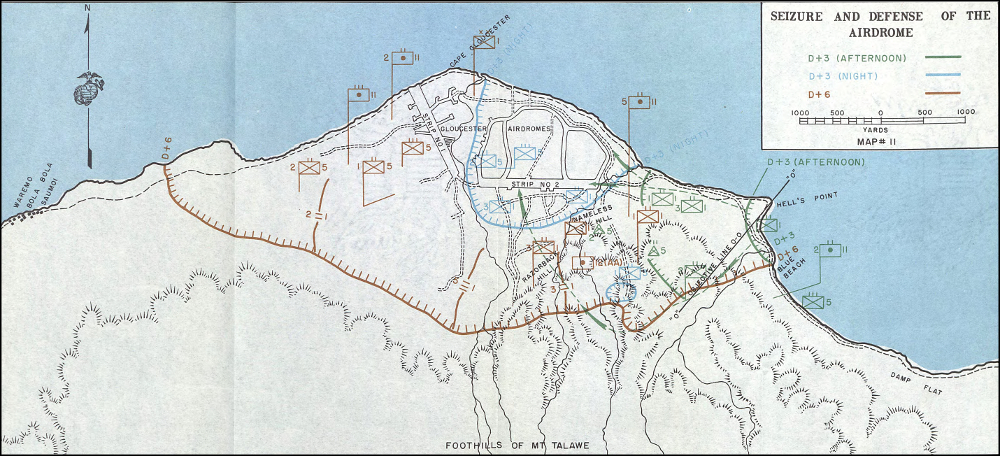

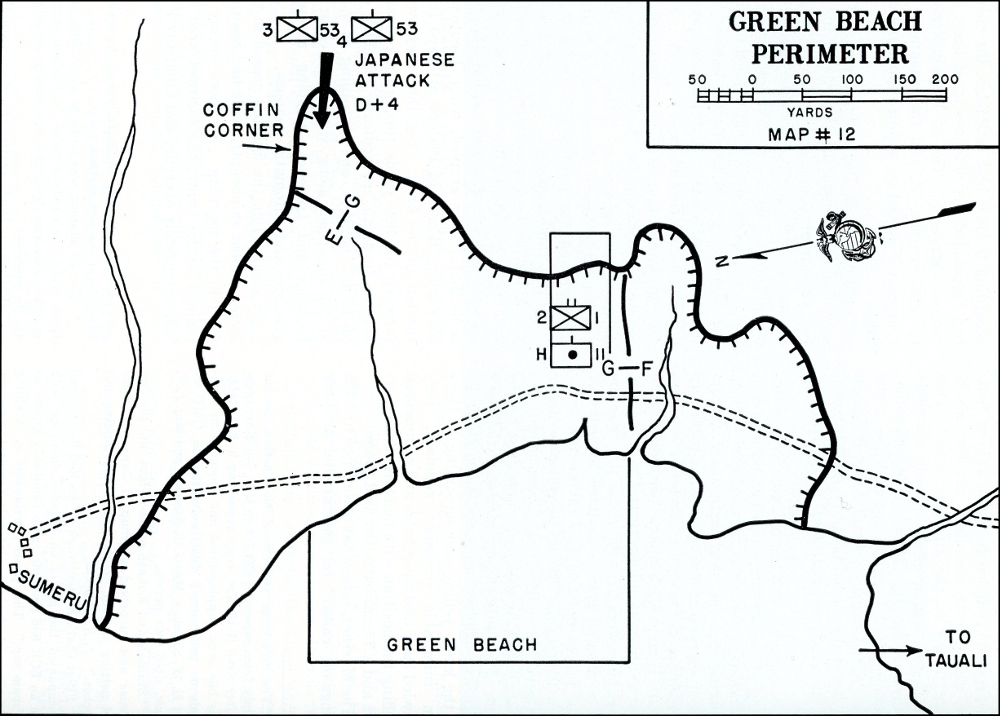

The Landing

On D-Day, LT21, 2nd Battalion/1st Marines (2/1) with Battery H of 3rd Battalion 11th Marines (3/11), would make a diversionary landing on Green Beach near Tauali on the western side of the Cape (Figure 16), with the additional intent of blocking trails along the coast to and from the airstrips. Simultaneously, the 1st Marines (minus the 2nd Battalion) along with the 2nd Battalion 11th Marines (2/11), and the 7th Marines along with the 1st & 4th Battalions 11th Marines (1/11 & 4/11) would land on Yellow Beaches 1 & 2 on the east side of the Cape. The 5th Marines, along with the 5th Battalion of the 11th Marines (5/11 - Corporal Moore's unit) stood by in reserve at Oro Bay ready to go aboard ship on call. Both landings would be supported by naval units from the Seventh Fleet and aircraft of the First Air Task Force (FTAF), Fifth Air Force.

D-Day was planned for December 26, 1943. On December 15, a combined Army and Marine force landed against a small Japanese garrison at Arawe on the south-central coast of New Britain (Figure 17). In addition to securing the Arawe peninsula, the operation's objective was to block a Japanese reinforcement route and serve as a diversion from the landings at Gloucester. It did succeed in diverting an estimated 1,000 Japanese troops away from Gloucester in response to the Arawe assault.

By December 18, 1943, Combat Team C would be assembled at Oro Bay (Cape Sudest) and Combat Team B at Finschhafen (Cape Cretin). Combat Team A would be held in reserve at Milne Bay with instructions to arrive at Oro Bay on D-minus 1 (Figure 18).

At 0600 on December 25 (D-Day-1), after final assembly at Buna Harbor on Cape Sudest, the convoy started moving northward. Meanwhile at Cape Cretin, Combat Team B (with the exception of LT21) had completed loading and was prepared to join the convoy on its way from Buna. LT21 had started its own convoy and departed at 1600 headed toward Green Beach at Tauali via Dampier Strait.

The pre-landing bombardment of Cape Gloucester by bombers and fighter bombers from the US Fifth Air Force occurred for several months in advance of D-Day, which put the Japanese's airfields out of action and destroyed many of their entrenchments. Air support continued up to and including D-Day when, in concert with Naval gunfire from escorting cruisers and destroyers, heavy bombers (B-24s), medium bombers (B-25s), light bomber/attack aircraft (A-20s), and fighter aircraft (P-38s), helped prepare the landing beach areas and suppress enemy fire.

This excerpt from The Campaign on New Britain describes the start of D-Day at Cape Gloucester:

During the early hours of 26 December, Christmas Day back home across the International Date Line, the main convoy turned to starboard from Vitiaz Strait, passed around Rooke (Umboi) and Sakar Islands, and bore in toward Cape Gloucester from the northwest. First dawn paled the sky to show the brooding hulk of Mount Talawe looming off to the southward, but darkness still lay upon the water at 0600 when the cruisers and destroyers opened fire on their predetermined targets. For the next hour and a half distant thunder beat upon the eardrums, and concussion shook the air. Only one Japanese gun replied - with a single round."

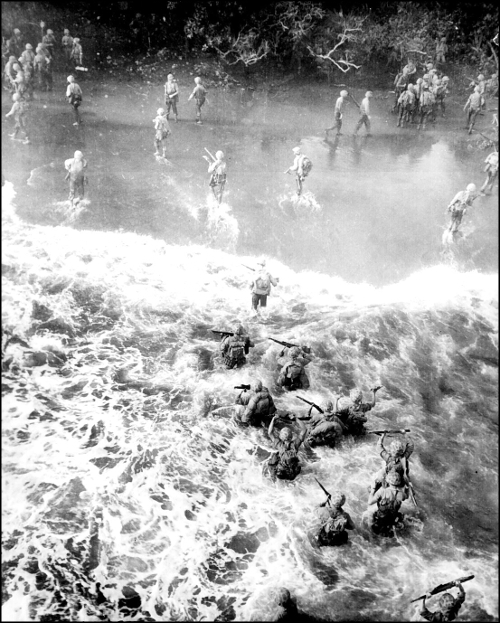

Earlier, under cover of darkness, destroyers and mine sweepers had preceded the convoy through the reef opening and marked shallow shoals with buoys. APDs and rocket-equipped LCIs then led the way through the reef opening, landing craft were deployed, and troop-carrying LCIs formed up behind, followed by LSTs. Prior to the assault at 0730 on Yellow Beaches 1 & 2, a white phosphorus smoke-screen was deployed to obscure the landing areas.

The three battalions of the 7th Marines were the first to land (3/7, 1/7 and 2/7 in that order) and were all ashore at Yellow Beaches 1 & 2 by 0805, followed soon after by the 1st & 3rd Battalion, 1st Marines (1/1, 3/1) at Yellow Beach 1. The landings were virtually unopposed on the ground with the exception of a small firefight 3/7 was involved in when they were blinded by the white phosphorus smoke-screen and landed 300 yards to the west of Yellow Beach 1. There was Japanese opposition from bombers launched out of Rabaul. A few bombers managed to evade Allied P-38s and sink the destroyer USS Brownson (DD-518) with the loss of 108 of her crew, far exceeding the 21 Marines killed and 23 wounded ashore on D-day.

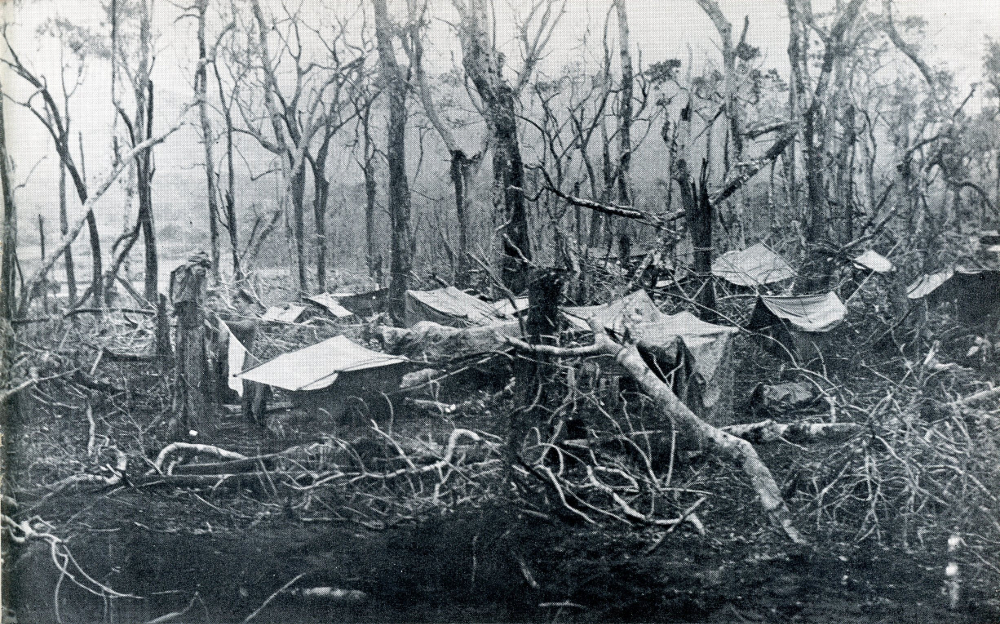

Although the Japanese failed to muster significant opposition to the landings at Cape Gloucester, nature took their place - the nature of the environment inshore of the landing areas. The beaches were fine for the landing craft but the above-water portions were extremely narrow and backed by vegetation so impenetrable that it could only be traversed by machete: "A tall man could lie with his head under the cover of the vegetation line and his feet out in the water."

To make matters worse, behind the initial wall of vegetation was a primitive transport road connecting the airfields to Borgen Bay, and then a narrow shelf of dry ground backed by a region described by the planning map makers as a "Damp Flat" extending inland up to a thousand yards or more (Figure 23). "Damp" turned out to be an extreme understatement. As described by one of the men, "It was damp up to your neck." Some speculate that part of the reason why the landings at the Yellow Beaches were unopposed was because the Commander of the Japanese 65th Division (later determined to be a regiment) on New Britain, Major General Iwao Matsuda, reasoned that, knowing the treacherous conditions behind those beaches, the Allied military planners would not direct the landings there.

"This was, as Matsuda well new, swamp forest, some of the most treacherous terrain that exists. Forward momentum petered out as the men floundered through the mud, tore loose from the vines that gripped their bodies. In places water lay hip-deep above the earth; in other places, what appeared to be solid ground would give way under a man's weight, dropping him up to his thighs in the muck and holding him there helpless until his companions could extricate him. And the trees began to fall: great forest giants, rotten to the core and further weakened by bombing and shell fire, crashed at the slightest provocation. The first fatality suffered by the troops ashore was caused by a falling tree."

Source: The Campaign on New Britain

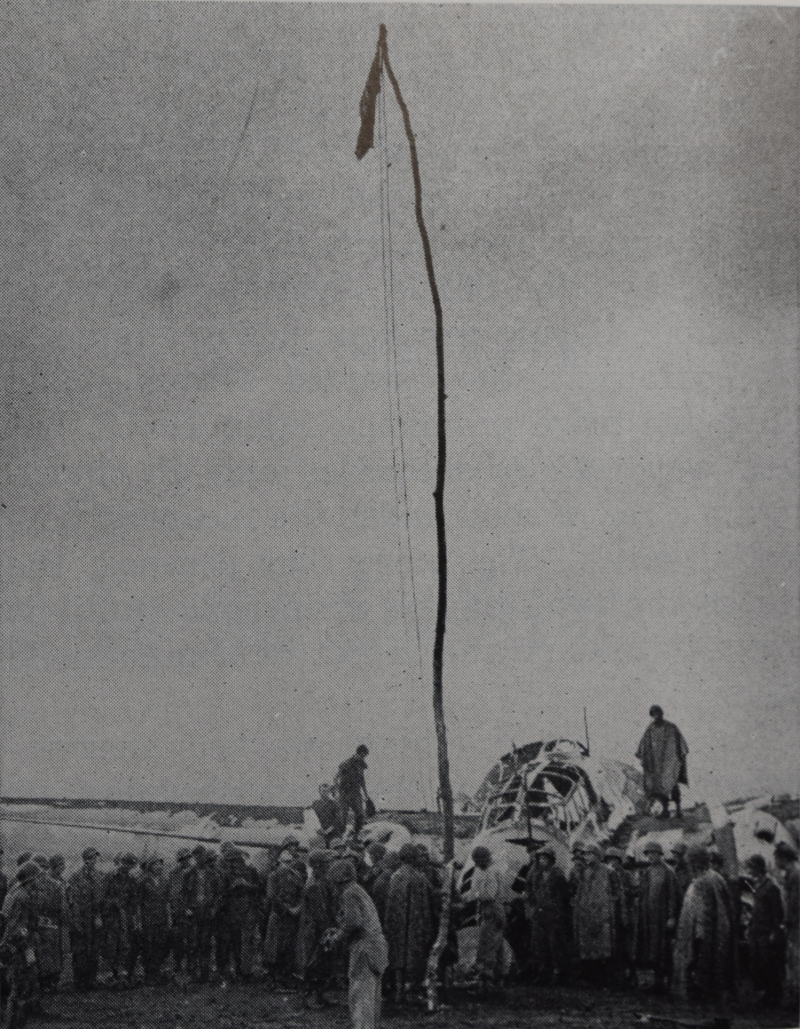

Note: If you look closely (click to enlarge) at the third Marine up from the bottom in the above photo, you will see that he is carrying a spool of wire and the Marine just behind him is helping to play out the wire as the men move along. That activity of "laying, maintaining, and taking up wire or cable" would be part of the job of a Telephone Man (TP MAN), which was the MOS for Corporal Chuck Moore during his time on Cape Gloucester.

From D-Day onward, throughout its duration, the battle of Cape Gloucester continued to be defined by the geography, the jungle, and the unremitting rain. The campaign was planned to coincide with the onset of the monsoon season. It began to rain on the afternoon of D-Day and rarely stopped during the next three months. The action report indicated that on early morning of December 27th, "a terrific storm struck the Cape Gloucester area." It goes on to say that, "Rains continued for the next five days. Water backed up in the swamps in rear of the shore line, making them impassable for wheeled and tracked vehicles. The many streams which emptied into the the sea in the beachhead area became raging torrents. Some even changed course. Troops were soaked to the skin and their skin and their clothes never dried out during the entire operation." As explained in the The Old Breed:

The fighting man expects that his vocation will carry him to unlikely and alien places. That is all right. It is one of the things he may look forward to. But there is a degree of strangeness beyond the bounds of the bargain, the bargain being: the natural hazards of the battlefield must never equal the hazards contrived by the enemy.

Break this law, put a fighting man down in a spot where the plant and animal life and the climate are as much or more of a menace to his existence than the armed human opposite him, and the fighting man will feel he is the victim of an injustice.

That is why the men who fought at Cape Gloucester remember the place more for the jungle than for the Japanese.

The forest has a structure: "the lower limits are on the ground, the upper the forest roof, supported by the forest skeleton, the trunks of the giant trees. Not only is the forest roof thick, but also even in still stronger measure, the forest margin is closed by the overwhelming mass of lianas which frequently extend to the ground, and which can form so thick an undergrowth that the forest has been accurately called impenetrable."

With a fact of climate, the description will be complete: in late December the northwest monsoons come to New Britain and for three months subject the island to one of the heaviest concentrations of rain that falls anywhere on earth.

Source: 'THE OLD BREED: A History of the First Marine Division In World War II'Robert Leckie landed on Green Beach on D-Day as a member of H Company, 2nd Battalion, 1st Marines. In his outstanding book Helmet for My Pillow: From Parris Island to the Pacific, A Marine Tells His Story (one of the chronicles that the HBO miniseries "The Pacific" is based on), he provides a more personal description of the "hell" that was New Britain:

The puffing of my lips and eyes symbolized the mystery and poison of this terrible island. Mysterious—perhaps I mean to say New Britain was evil, darkly and secretly evil, a malefactor and enemy of humankind, an adversary, really, dissolving corroding, poisoning, chilling, sucking, drenching—coming at a man with its rolling mists and green mold and ceaseless downpour, tripping him with its numberless roots and vines, poisoning him with green insects and malodorous bugs and treacherous tree bark, turning the sun from his bones and cheer from his heart, dissolving him—the rain, the mold, the damp steadily plucking each cell apart like tiny hands tearing at the petals of a flower—dissolving him, I say, into a mindless, formless fluid like the sop of mud into which his feet forever fall in a monotonous slop-suck, slop-suck that is the sound of nothingness, the song of the jungle wherein everything falls apart in hollow harmony with the rain.

Nothing could stand against it: a letter from home had to be read and reread and memorized, for it fell apart in your pocket in less than a week; a pair of socks lasted no longer; a pack of cigarettes became sodden and worthless unless smoked that day; pocketknife blades rusted together; watches recorded the period of their own decay; rain made garbage of the food; pencils swelled and burst apart; fountain pens clogged and their points separated; rifle barrels turned blue with mold and had to be slung upside down to keep out the rain; bullets stuck together in the rifle magazines and machine gunners had to go over their belts daily, extracting and oiling and reinserting the bullets to prevent them from sticking to the cloth loops—and everything lay damp and sodden and squashy to the touch, exuding that steady musty reek that is the jungle’s own, that individual odor of decay rising from vegetable life so luxuriant, growing so swiftly, that it seems to hasten to decomposition from the moment of birth.

It was into this green hell that we were inserted a day or two after the march from Tauali-Sag Sag. And here was fought that battle with the rain forest, here the jungle and the men were locked in a conflict far more basic than our shooting war with the Japanese—for here the struggle was for existence itself.

The war was forgotten, Who could comprehend it? Who cared? The day was but twenty-four hours and the mind had but two or three things to command it, objects like dryness, food—oh, most of all, most unbelievably of all, a cup of hot coffee—a clean, dry pair of pants and a place out of the rain! Hours passed in precocious contemplation of that moment just before darkness, when—with cigarette wrappings and the wax-paper covers of the K-rations, with matches carefully wrapped in a contraceptive and kept within the liner of the helmet—a tiny fire was lighted and water heated in a canteen cup, and thus was the belly fortified to face the cold black night.

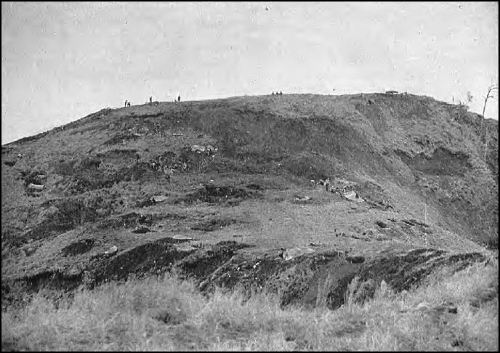

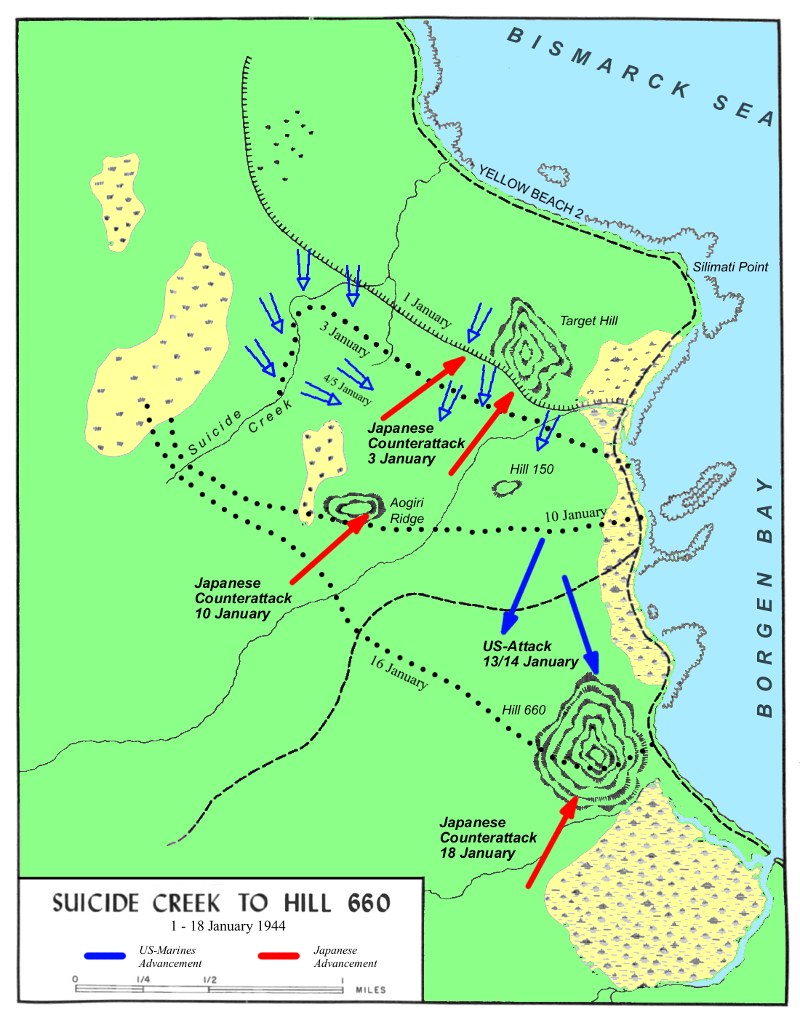

The initial objective of the 7th was to push inland and establish a defensive perimeter south and west of the beaches (Figure 23). This effort was to include occupying the high ground of a small hill (Target Hill/Hill 450) south of Yellow Beach 2. Target Hill had been decimated by the pre-landing bombardment and so was unoccupied and soon taken by men of 1/7.

The assignment for 1/1 and 3/1 was to land on Yellow Beach 1, turn right, and spread out abreast across a wide front from the coast inland as soon as possible, hook up with 3/7 to form a defensive perimeter, and move northwest along the coast toward the Cape Gloucester airfield with the objective of capturing it. This plan immediately ran into trouble as 1/1 attempted to go into position left of 3/1 and ended up bogging down in the "damp flat". To address this problem, the plan was quickly changed; 3/1, led by Lieutenant Colonel Joseph F. Hankins, would move along the narrow shelf adjacent to the coast with 1/1 in echelon to their rear. They would rely in part on the damp flat to protect their left flank (Figure 23). They soon encountered opposition:

While reinforcements and cargo crossed the beach, the Marines advancing inland encountered the first serious Japanese resistance. Shortly after 1000 on 26 December, Hankins's 3d Battalion, 1st Marines, pushed ahead, advancing in a column of companies because a swamp on the left narrowed the frontage. Fire from camouflaged bunkers killed Captain Joseph A. Terzi, commander of Company K, posthumously awarded the Navy Cross for heroism while leading the attack, and his executive officer, Captain Philip A. Wilheit. The sturdy bunkers proved impervious to bazooka rockets, which failed to detonate in the soft earth covering the structures, and to fire from 37mm guns, which could not penetrate the logs protecting the occupants. An Alligator that had delivered supplies for Company K tried to crush one of the bunkers but became wedged between two trees. Japanese riflemen burst from cover and killed the tractor's two machine gunners, neither of them protected by armor, before the driver could break free. Again lunging ahead, the tractor caved in one bunker, silencing its fire and enabling Marine riflemen to isolate three others and destroy them in succession, killing 25 Japanese. A platoon of M4 Sherman tanks joined the company in time to lead the advance beyond this first strongpoint.

Source: Cape Gloucester: The Green InfernoThe new plan sped up movement of 1/1 and 3/1 along the coast but it also caused 3/7, slogging through the damp flat on their left, to fall behind while trying to maintain the defensive perimeter. This opened a gap in the perimeter that allowed a small group of Japanese to infiltrate. As a result, 3/7 was ordered back to the main beachhead line, and 1/1 and 3/1 were tasked with setting up their own perimeter as they advanced.

According to the Division Special Action Report, in the early morning hours of the 27th, "a terrific storm struck the Cape Gloucester area". This was a prelude to monsoon conditions that would persist over the course of the next three months and virtually eliminated any dry ground upon which to move equipment, supplies, and Marines in the areas of the beachheads and along the coastal route. The Japanese commander, General Matsuda, choose this time to counterattack against the landing force.

The defensive perimeter behind the Yellow Beaches, was comprised of 3/7 on the right, 2/7 in the middle, and 1/7 on the left (Figure 23). Late in the afternoon of D-Day a Japanese battalion-size force moved into position opposite of 2/7 in preparation for the counterattack. Exchange of fire escalated in intensity after sunset and 2/7, led by Colonel Odell M. Conoley, began to run low on ammunition. The amtracks supplying ammunition from the beachheads, could not resupply 2/7 at night because they could not see to avoid the fallen trees and roots as they maneuvered across the damp flat. In recognition of the problem, Colonel Lewis B. Puller (better known among his men as "Chesty" Puller), executive officer of the 7th Marines, organized available Marines into supply parties to wade through the swamps carrying ammunition to 2/7 at the far edge of the damp flat - a very hazardous mission given that a misstep could cause a Marine, weighed down by heavy ammunition, to disappear under the water and drown. This mission was carried out during a blinding monsoon rain storm with each Marine hanging on to the belt of the Marine in front of him. Some twelve hours after the column started, they reached 2/7 and put down their loads to take up their rifles. After a desperate fight by the men of 2/7 to hold off the Japanese during the night, the Marine reinforcements, along with the ammunition they brought in, caused the Japanese to break off the action.

11th Marines at the Gloucester D-Day Landing

Units of the 11th Marines accompanied all of the landings on D-Day. Faced with the difficult terrain, the 4th and 1st Battalions, 11th Marines, in company with the 7th Marines, were able to establish firing positions near the Yellow Beaches with the aid of amphibious tractors and bulldozers that broke trail and pulled them into position. The 4th battalion (4/11) had to drag its 105mm howitzers through 400 yards of "damp flat" in order setup in a large kunai (tall grass) patch in support of the attack on the airfields (Figures 26 & 27). They remained there until their departure from New Britain.

The 1/11 was assigned a position on Silimati Point (Figure 23). To get there they had anticipated moving their 75 mm pack howitzers along the coastal trail but were stymied by trees that had been felled by the pre-attack bombardment and had to take a beach route instead. Arriving at their destination, they found a swamp instead of the "scattered trees" they had expected and had to setup positions on the adjacent beach. Their difficulties were exacerbated when gunners on ships in the convoy mistook US B-25s for enemy aircraft. Two of the American bombers were downed and other bombers in the flight were disrupted to the extent that they dropped their bombs prematurely on the artillery positions of the 1/11, killing one officer and wounding 14 enlisted. Later that afternoon, the 1/11 was attacked by a small group of Japanese troops and one officer and five enlisted were killed in the ensuing fight. The 1/11 remained at their position on Silimati Point throughout the remainder of the campaign.

Note: Of great value in navigating the swamps of Cape Gloucester were the LVTs (Landing Vehicle, Tracked) that were brought ashore by the LSTs (Figure 28). They were variously referred to as "amphibious tractor", "amtrak", "amtrac", "alligator", and "gator". They were unique in that they could travel over land, including rain-soaked muddy bogs, roads, and trails with their tank-like tracks, but could also float and so maneuver through the flooded portions of the "damp flat". They were used for a wide variety of purposes but were of particular value to the 11th as a means of hauling artillery into position.

The LVTs also often provided the only mechanical means of crossing the swamps to bring/ food and ammunition to Marines fighting in areas beyond the swamps. However, this provided one downside - their treks through the jungle resulted in their treads chewing up many miles of telephone wire. This was likely frustrating to Corporal Moore in that, as a telephone man, he would have been responsible to laying a portion of that wire.

The 2nd Battalion (2/11) in company with the 1st Marines were not faced with the "damp flat" problem and were able to displace their 75mm howitzers forward twice along the coast in support of the 1st's assault on the airdrome. They remained at the airdrome until February 23, 1944 when they joined the 5th Marines in mop-up operations at Iboki and Talasea.

Battery H, 3rd Battalion, 11th Marines, in company with 2nd Battalion, 1st Marines (LT21 Group), landed on Green Beach near Tauali on D-Day. Once the Green Beach operation concluded, LT21 joined its parent command at the airfield and Battery H came under control of 2/11 until its parent Battalion, 3/11, left New Guinea and joined the Division at the airdrome on February 19, 1944.

On D-Day Corporal Moore's unit, 5th Battlion, 11th Marines, in company with the 5th Marines, was still being held in reserve at Oro Bay. They would soon be called up to join the battle.

Summary of the D-Day Landings

In retrospect, the landings at Cape Gloucester were considered a success as conveyed in "The Campaign on New Britain":

What the Marines did know was that they had effected a remarkably efficient landing on terrain described by their commanding general as "the most difficult that I have ever encountered in landing operations." Establishment of the beachhead perimeter and commencement of the drive on the airdrome had cost the division 21 killed in action and 23 wounded. The next day enemy counteraction added eight killed and 45 wounded to the D-Day figures. Estimated Japanese casualties approached the 300 mark.

Although the terrain had proved worse than the planners had anticipated, and the weather worse than the uninitiated could have imagined, Japanese ground resistance had been less severe than expected, their air resistance impotent. All troops were ashore safely, together with their equipment, including rolling stock, tanks and artillery. Dump dispersal had failed to measure up to optimistic advance plans owing to proximity of the island swamps; yet in addition to assault landing craft, 14 LST's had been completely unloaded of their vehicles and 55% of their combined bulk cargo, and the difficult shore party problem momentarily solved. The main perimeter stood firm, and a substantial start had been made on the airdrome drive, even if not exactly in the manner planned.

Source: The Campaign on New BritainAdvance on the Airfield

The logistics and effort required to support the Japanese attack on Conoley's 2/7 battalion on the night of the 26th/27th, prompted General Rupertus to request the release of the division reserve, Combat Team A, the 5th Marines. The nature and timing of the planned movement (from Milne Bay to Oro Bay) and subsequent call-up for Combat Team A (5th Marines reinforced by 5th Battalion, 11th Marines) corresponds with Chuck Moore's service record:

- 12/24/43 to 12/26/43 - Embarked on board USS Etamin at Milne Bay, New Guinea and arrived at Cape Gloucester, New Britain. The reference to Cape Gloucester in this movement is likely incorrect (should be Oro Bay) given that, 1) Combat Team A had been standing by at Oro Bay on D-Day, 2) the USS Etamin was a Liberty ship and would not have been used to carry troops into the landing zone and, 3) Corporal Moore's next documented movement was:

- 12/28/43 to 12/30/43 - Embarked on board USS LST #202 at Oro Bay, New Guinea and arrived at Cape Gloucester, New Britain."

The decision was made to land the 5th Marines on Blue Beach (Figure 32) which would place them three miles northwest of the Yellow Beaches and that much closer to the airfields. Two battalions, 1/5 and 2/5, landed on the 29th, and 3/5 along with Corporal Moore's battalion 5/11, landed a day later.

Meanwhile, as they advanced northwest along the coast, the Marines of 3/1 and 1/1 met little to no resistance through the 27th. This indicated that the Japanese had likely made the decision to withdraw and concentrate on more favorable ground in defense of the airfield. One of these positions was a point of land (designated as Hell's Point - Figure 32) that flanked a crescent-shaped beach 1000 yards east of the airdrome. This location had been identified earlier by aerial reconnaissance as containing a system of prepared defensive positions.

In preparation to attack, 11th Marine artillery directed fire on the point and the Fifth Air Force conducted bombing and strafing missions. The infantry advance began at 1000 and at 1200 Marines moving along the coastal road began to receive small arms fire and 75 mm shelling. At 1215 they came upon the first of the prepared positions consisting of mutually supporting bunkers and rifle positions well armed with antitank guns and 75mm artillery, and obstructed with wire and land mines. These were originally designed to defend against beach landing but were partially modified over the previous two days to address a land attack.

The Marines of 3/1 attacked the prepared bunkers with three tanks, each escorted by infantry. They encountered twelve huge bunkers with 20 Japanese in each. The tanks fired directly into the bunkers and any escaping Japanese were killed by rifle fire and grenades. Twelve bunkers were destroyed with another two abandoned before they could be attacked.

While the fight was developing against the prepared positions, Company A of 1/1 moved into a large kunai grass patch 500 yards inland where they came under fire from a company-sized enemy force utilizing prepared interlocking firing lanes in the tall grass. The ensuing fire fight lasted four hours, the Marines breaking up two frontal assaults and one attempt to turn their flank. Around 1545, with ammunition running low, Company A withdrew toward the beach covered by artillery and rifle fire. The forward observer from the 11th Marines remained behind to call down fire on the enemy positions. The next morning 41 dead Japanese were found in the abandoned position. The Marines had lost eight dead and 16 wounded.

By removing the threat on Hell's Point, the last effective defenses of the airdrome were successfully destroyed. Losses for 3/1 were nine killed and 36 wounded versus 266 dead Japanese. Hell's Point was later renamed as Terzi Point in honor of Company K's commanding officer, who had been killed in action on D-Day.

As 3/1 and 1/1 advanced up the coast, they were followed by the engineers of the 17th Marines (Seabees) working continuously to widen and maintain the muddy and washed-out coastal road which was subject to constant rain and further degradation by wheeled and tracked vehicles. Given the extreme conditions, the men of the 17th were unable to keep up, jeopardizing efforts to bring food and ammunition forward and carry the wounded back. Fortunately, capture of Hell's Point opened another usable beach, designated Blue Beach, which would be utilized to bring supplies via water as well as provide a landing location for the arrival of the 5th Marines on the 29th and 30th.

Note: Shortly after the fight, on the 28th, the command post was displaced forward in order to maintain closer contact with the 1st Marine's drive on the airdrome. This necessitated moving the general and his staff beyond the main perimeter and, thus a requirement for an strong security guard. This duty fell to the division band which did most of the work around the CP - another example of "all marines are of the line" regardless of assigned MOS:

During the two nights that the CP occupied this second position, the bandsmen were supplemented by the Public Relations Section, manning what was probably one of the most expensive two-man security posts on record: two captains, a master sergeant, two technical sergeants and a civilian newspaper correspondent standing four-hour watches. The Japanese proclivity for shooting everybody in sight eliminated the noncombatant from the Pacific war; doctors, medical corpsmen, civilians, even chaplains carried weapons—and used them.

Source: The Campaign on New Britain

Nine APD's carrying the the 1st and 2nd battalions of the 5th Marines arrived off Cape Gloucester early on the morning of the 29th. The landing location was originally designated as Yellow Beach 2 but was changed to Blue Beach after Hell's Point was cleared. Some of the landing party elements did not get the change notice and so landed at Yellow Beach 2 and then proceeded to Blue Beach to hook up with the remaining elements.

Shortly after landing, The commander of the 5th, Colonel John T Seldon, conferred with General Rupertus and his command team and the decision was made for 1/1 to continue its attack along the coast road while the 5th made a sweep to the southwest to cut off enemy withdrawal from the airdrome vicinity, and then press the attack on the No. 2 airstrip (Figure 32) through an area thought to contain prepared enemy defenses.

Note: These are the symbols used in the maps provided in The Campaign on New Britain, such as Figure 32. Some examples: